EDITOR’S NOTE

By Andrew Tonkovich

I hope you welcome the opportunity, at this moment of particular challenge, grief, anger and, yes, more reasons to do something in response, to read some terrific work. It addresses so much of what we are observing, sharing, and working on individually and together: writing, family, community, and civic engagement. The newest issue of the OGQ offers a short if rich survey of the engagements, interests, and experiences of a range of our staff and alums, in a variety of genres. They are candid and generous in both their own challenges and celebrations. We’re lucky to include fiction, creative nonfiction, remembrance, poetry, craft essays and art.

We’re hoping this organized tumult of beauty, empathy, creativity, and wisdom gives you inspiration, insight, and courage.

Andrew Tonkovich

Editor, OGQ

LIVING PROOF

By Tyler Dilts

When you get the call, you’re sitting on the couch rubbing your seven-and-a-half-months-pregnant wife’s feet, both of you exhausted from the baby shower earlier that day. You look into her tired eyes and when she looks back at you there’s a kind of happiness and hopefulness you wouldn’t have been able to comprehend before the IVF and the ultrasounds and that first movement you felt when she took your hand and gently pressed your palm into her abdomen.

But then your brother’s name on the caller ID makes your throat constrict and it’s suddenly difficult to fill your lungs. You were expecting a text. He always texts you after he visits your mom at the Pacifica Senior Living Newport Mesa memory care center every weekend. You try to remember a time when he’s actually called but there’s nothing.

Is she gone?

She can’t be.

The hospice nurse was concerned last week, but your mom rallied and seemed to be out of immediate danger.

Like she could maybe hold on.

Like she could maybe make it six more weeks.

Like she could maybe meet her granddaughter.

You answer the call. It’s neither as good as you hoped nor as bad as you feared. He says you should visit tomorrow. Just in case.

#

You don’t sleep much that night.

You take some lorazepam.

You take some more lorazepam.

You search the Calm app on your phone and try a sleep meditation. “Drifting Off with Gratitude” doesn’t help.

Neither does “Letting Go into Sleep.”

Not even “Deep Rest” does you any good.

You take out your ear buds and listen to your wife breathing in her sleep. You try to focus on the laughter and hopefulness of the baby shower. That works. For a few minutes at least.

The clock tells you it’s 3:15.

When you look at it again a few minutes later it says 4:52.

You figure you must have fallen asleep for a while even though you’re sure you never closed your eyes for anything longer than a blink.

Eventually the sun comes up.

#

You know that even though the last year, two years, three years have seemed endless, they weren’t. The impossible is almost here. After so very long, it seems so sudden.

For the last few months, even after she lost your name, even after the fading hint of recognition disappeared completely, there was still one way you could make her smile and make her eyes brighten.

You’d lean in, hold her hand, and say softly, “We’re having a baby, Mom. Charlotte’s coming. You’re going to be a grandma.”

#

You’re glad it’s Sunday and your wife doesn’t have to go teach her AP English classes.

When she offers to drive, you feel guilty.

But not guilty enough to decline the offer.

Before she starts the car, she puts her hand on your leg and offers you a sad smile. She knows better than to say, “It’s going to be okay.”

You haven’t heard anything new, and you tell yourself that’s a good thing. The hospice nurse would have called you if things had gotten any worse.

You’ve already forgotten it’s Sunday, though, so she might have called your brother because even though he only lives five minutes from the Pacifica Senior Living Newport Mesa memory care center, and if there’s no traffic, you’re almost half an hour away, he’s the weekend guy and you’re the Monday-Friday guy. That’s okay, though, because he has a real job and he pays for your mom’s very expensive care with money and you’re an adjunct English instructor so you pay with time.

When you’re about halfway there, right at the beginning of that part of the 405 that’s been under construction for as long as you can remember because no matter how many lanes they add it will never be enough, you start watching all the Caltrans roadwork signs zoom by.

You’re so focused on those orange flashes that you never even see the car that lurches out of the merge lane and sideswipes you.

#

The funny thing is you never even wanted kids.

You really didn’t want kids.

Then you didn’t want kids.

Then you didn’t think you wanted kids.

Then you got married.

Then you wanted kids.

But by then you were getting pretty old.

Fortunately, your wife was a little bit less old.

So you tried and it didn’t happen.

So you saw the fertility specialists.

Then it happened.

Then the miscarriage.

Then the IVF.

Then it happened again. And you knew, though you’d never dare speak the words out loud, this was your last chance.

#

The shock and the panic are overwhelming, but as you’re standing on the side of the freeway talking to the CHP officer you realize the aftermath of the accident itself is neither as good as you’d hoped nor as bad as you feared.

No one seems to be injured.

Your wife’s car is still drivable.

You don’t even have to think about it.

You are afraid this will be the last day you see your mother before she dies, but you know, without the slightest tremble of doubt, what she’d want you to do.

You take your wife to the emergency room.

#

Somewhere between a few minutes and several hours later, they give you and your wife the good news—there don’t seem to be any complications at all from the accident.

You exhale and start to—

But.

But?

“It’s a good thing you came in when you did,” they tell your wife. “You have preeclampsia. We’re going to have to induce labor tonight and deliver your baby.”

Tyler Dilts is the author of five novels, including the Edgar Award-nominated Come Twilight and the #1 Amazon Bestseller, A Cold and Broken Hallelujah. He earned his MFA in Fiction from California State University, Long Beach where he now teaches fiction writing and narrative theory. He also served as the Visiting Writer at John Cabot University in Rome and taught as visiting faculty at the UCR Palm Desert Low Residency MFA Program. His most recent novel, Mercy Dogs, is currently being developed as a TV series by Bad Wolf Productions.

Tyler Dilts is the author of five novels, including the Edgar Award-nominated Come Twilight and the #1 Amazon Bestseller, A Cold and Broken Hallelujah. He earned his MFA in Fiction from California State University, Long Beach where he now teaches fiction writing and narrative theory. He also served as the Visiting Writer at John Cabot University in Rome and taught as visiting faculty at the UCR Palm Desert Low Residency MFA Program. His most recent novel, Mercy Dogs, is currently being developed as a TV series by Bad Wolf Productions.

PARALLEL LIVES: REMEMBERING PAUL AUSTER

by Susanne Pari

When I was offered a chance to participate in last summer’s evening event called “You Must Read This: The Narrative Technique That Stopped you in Your Tracks,” I thought immediately of Paul Auster. I’d recently finished reading his 2017 novel, 4 3 2 1, which examines four parallel versions of a protagonist’s life. I was dubious, as I am with anything labeled “experimental,” and coming in at a page count of nearly nine hundred, it was a serious commitment. I gave myself permission to “not finish, but try,” and was unexpectedly hooked by a straightforward character-driven story with depth and humor and the kind of intimacy I admire. By the time Auster turned everything on its head in order to explore the “what ifs” that fueled his imagination, I didn’t care how much my shoulder hurt from carrying his tome around.

What I found most fascinating was Auster’s belief that life and story are layered and infinite. Coincidence and chance spark endless narratives that we must contemplate and tell, both in fiction and in life. As his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt, said: “‘He was articulating the complex patterns of often unpredictable interactions that affect every life, and which became part of his fiction.”

At the conference, I read the opening pages of 4 3 2 1, and I hope the words Auster wrote that rolled easily off my tongue inspired others to take a look. But Auster on the page was not the only reason I chose to read from his work at the Conference. He was a master storyteller off the page too, and he belonged to a large community of writers to whom he told those stories. I, too, believe so strongly in the nurturing creativity of face-to-face storytelling between writers that I couldn’t help but have an ulterior motive when I chose to read Auster at the Community of Writers.

In 1996, Auster wrote a New Yorker essay asserting that his writing life began at the age of eight when he missed out on getting an autograph from his baseball hero, Willie Mays, because neither he nor his parents had carried a pencil to the game. From then on, he always carried a pencil in his pocket. Cool story.

In 2007, when Auster was about to turn sixty, Amy Tan wanted to give him a special present. She called me…turns out Willie Mays was my next door neighbor. You see, Amy and I got to know one another when CW staffer Molly Giles invited me to join her writing group back in 1989; that’s when my “writing community” became a reality, and it has only grown and deepened since then. Without it, I can honestly say I may never have finished any of my books nor lived a less-than-miserable life (truly).

Anyway, the day after Amy’s call, I sent my husband Shahram next door. He sat in Willie’s den and read him Paul’s essay about the pencil and the elusive autograph. Reclining in his Barcalounger, he listened with his eyes closed, then said, ‘Wow, fifty-two years ago!’ and he gestured to his box of signed balls so Shahram could take one for Amy to give to Paul. Oh, and then he autographed Paul’s book, which was weird, but I guess we couldn’t expect him to know how our world worked.

While I never met Auster—he died last year, way too soon—I heard him tell this story on the air some years ago. And I can’t help imagining that it may have contributed to his beliefs about happenstance. Maybe it even nourished his idea to write a novel in which a protagonist lives four parallel lives, each one markedly different as a result of a small twist of fate.

Susanne Pari is the author of The Fortune Catcher, a novel of revolutionary Iran, and of In the Time of Our History, about an Iranian American family grappling with generational clashes and the rebellion of its women. It was an IndieNext pick, Target Book Club pick, 2023 Women’s National Book Association Group Reads Selection, and Hoopla Spotlight Selection. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The San Francisco Chronicle, and NPR. She is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and PEN America.

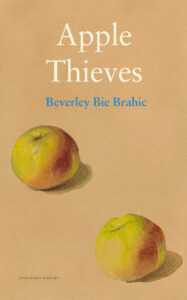

POEMS FROM APPLE THIEVES

by Beverley Bie Brahic

Apple Thieves

In his disheveled garden my neighbour

Has fourteen varieties of apples,

Fourteen trees his wife put in as seedlings

Because, being sick, she wanted something

Different to do (different from being sick).

In winter she ordered catalogues, pored

Over subtleties of mouth-feel and touch:

Tart and sweet and crisp; waxy, smooth

And rough. Spring planted an orchard,

Spring projected summers

Of green and yellow-streaked, orange, red,

Rusty, round, worm-holed, lopsided;

Nothing supermarket flawless, nothing imperishable.

Gardens grow backwards and forwards

In the mind; in the driest season, flowers.

Of the original fourteen trees, five

Grow street-side, outside the fence.

To their branches my neighbour, a retired

Accountant, has clothes-pegged

Slips of paper, white pocket handkerchiefs

Embroidered with the words:

The apples are not ripe, please don’t pick them.

Kids had an apple fight last week.

In September, when the apples ripen,

Passersby are welcome to pick them, even

Those rare Black Diamonds that overflow

The wall. Sure, I may gather the windfalls.

Mostly it’s squirrels that toss them down.

Squirrels are wasteful. Squirrels don’t read

Messages a widower posts in trees.

First published in the New Yorker

Born in Saskatchewan, Canada, Beverley Bie Brahic grew up in Vancouver; today she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and France. Apple Thieves is her fifth collection of poetry after Catch and Release, winner of the 2019 Wigtown Book Festival Alistair Reid Pamphlet Prize; The Hotel Eden; The Hunting of the Boar, a 2016 PBS Recommendation; White Sheets, a 2013 Forward Prize finalist for Best Collection and PBS Recommendation; and Against Gravity. Her many translations include books by Yves Bonnefoy, Hélène Cixous, and Charles Baudelaire; The Little Auto, her selection of Guillaume Apollinaire’s First World War poems, was awarded the 2013 Scott Moncrieff Translation Prize; Francis Ponge: Unfinished Ode to Mud, was a finalist for the 2009 Popescu Translation Prize. She has received a Canada Council for the Arts Writing Grant and fellowships at Yaddo and MacDowell.

YOU MUST LOOK!

by Andrew Tonkovich

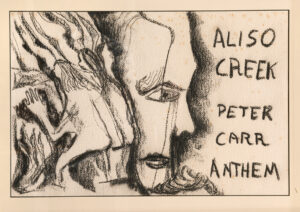

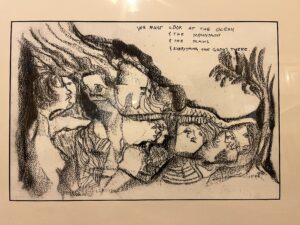

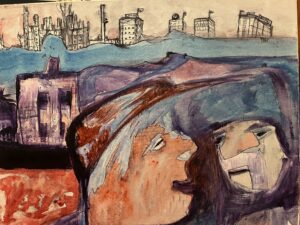

Friends, colleagues, fellow activists, and writer pals at the Community of Writers have for years cheerfully put up with my proselytizing for, writing about, and otherwise sharing the art, prose, and poetry of a mentor, artist, activist, writer, and university professor whose example, it turns out, I guess I took pretty sincerely. Knowing even just a little about one Harry “Peter” Lawson Carr (1925-1981) perhaps explains the kind of weirdo I am today. Carr was my long-ago teacher at California State University Long Beach and didn’t so much teach as aggressively live, whether via scholarship, creativity, critical thinking or political action. Born in Pasadena, Carr served in the US Navy, earned a PhD from USC, co-founded the CSULB Comparative Literature Department and, just when I’d sort of adopted him as my mentor, died suddenly at age fifty-five. But if we’ve never met or you don’t know my own writing, I think you’d like to know Peter anyway, whose record of unceasing engagement, creativity, and persistent wonder seems to keep making him friends — despite being dead for forty years. Some deal. Here’s the cover of what I argue is his best book, Aliso Creek, self-published, with drawings. He lived near Aliso Creek in Laguna Beach. Note the place, the people, and a version of the poet/artist himself.

Friends, colleagues, fellow activists, and writer pals at the Community of Writers have for years cheerfully put up with my proselytizing for, writing about, and otherwise sharing the art, prose, and poetry of a mentor, artist, activist, writer, and university professor whose example, it turns out, I guess I took pretty sincerely. Knowing even just a little about one Harry “Peter” Lawson Carr (1925-1981) perhaps explains the kind of weirdo I am today. Carr was my long-ago teacher at California State University Long Beach and didn’t so much teach as aggressively live, whether via scholarship, creativity, critical thinking or political action. Born in Pasadena, Carr served in the US Navy, earned a PhD from USC, co-founded the CSULB Comparative Literature Department and, just when I’d sort of adopted him as my mentor, died suddenly at age fifty-five. But if we’ve never met or you don’t know my own writing, I think you’d like to know Peter anyway, whose record of unceasing engagement, creativity, and persistent wonder seems to keep making him friends — despite being dead for forty years. Some deal. Here’s the cover of what I argue is his best book, Aliso Creek, self-published, with drawings. He lived near Aliso Creek in Laguna Beach. Note the place, the people, and a version of the poet/artist himself.

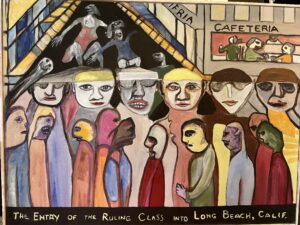

If you’re in Southern California this fall, I hope you might take in the show I’m co-curating with the excellent Cerritos College Art Gallery Director James MacDevitt, to whom I owe this big break. It’s an opportunity to share exemplary work from among the thousands of drawings, paintings, notebooks, published and unpublished writing I’ve been storing, cataloging, and cherishing for years. I’ll deliver a lecture at the opening, on Monday, October 28, with a PowerPoint featuring hundreds more of the images shared here, followed by an informal docent tour. It’s been hard to choose one to place at the entrance to the gallery, but James and I might pick “The Entry of the Ruling Class into Long Beach, CA,” an obvious if hilarious homage to Belgian painter James Ensor’s “Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889.”

opportunity to share exemplary work from among the thousands of drawings, paintings, notebooks, published and unpublished writing I’ve been storing, cataloging, and cherishing for years. I’ll deliver a lecture at the opening, on Monday, October 28, with a PowerPoint featuring hundreds more of the images shared here, followed by an informal docent tour. It’s been hard to choose one to place at the entrance to the gallery, but James and I might pick “The Entry of the Ruling Class into Long Beach, CA,” an obvious if hilarious homage to Belgian painter James Ensor’s “Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889.”

Or maybe we should go with this both politically unshy and ecologically themed piece, which I call “Orange San Onofre,” with lovely naked humans swimming in the Pacific Ocean just offshore of the (now-decommissioned) nuke plant just south of San Clemente.

Or maybe we should go with this both politically unshy and ecologically themed piece, which I call “Orange San Onofre,” with lovely naked humans swimming in the Pacific Ocean just offshore of the (now-decommissioned) nuke plant just south of San Clemente.

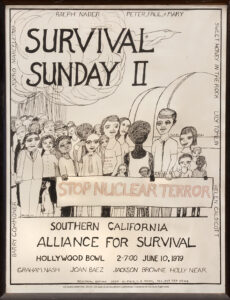

I love this job. It’s a labor of love, and I struggle in a child-like state of exuberance at explicating both labor and love. Peter had art, classics, myth, and literary chops. But he was also a bigtime opponent of nuclear power and the US nuclear-military machine, Nixon, Reagan, war, capitalism, golf, smog, smog, and development. He co-founded the Orange County chapter of the grassroots Alliance for Survival, of which I and thousands were members, attending rallies, concerts, and protests at Diablo Canyon and San Onofre.

Sharing this variety of quick biographical-historical detail is what I’m doing lately, staging not just a show but making decisions on behalf of a story, an artist, a revisionist history. You’d be surprised at how many times I’ve had to explain the once-ubiquitous anti-nuclear and peace movements of the late 1970s and popular anti-Reagan resistance. The art show has become a writerly project for this longtime editor (of three journals just now!) but first-time curator, with responsibilities including helping compose a press release, describing the paintings, summarizing and critiquing the books, contributing a short essay to the catalog, trying to be thoughtful in interviews, querying editors about possible commentaries or coverage, not to mention making up titles (as above!), scanning work, and creating a database of the material.

Sharing this variety of quick biographical-historical detail is what I’m doing lately, staging not just a show but making decisions on behalf of a story, an artist, a revisionist history. You’d be surprised at how many times I’ve had to explain the once-ubiquitous anti-nuclear and peace movements of the late 1970s and popular anti-Reagan resistance. The art show has become a writerly project for this longtime editor (of three journals just now!) but first-time curator, with responsibilities including helping compose a press release, describing the paintings, summarizing and critiquing the books, contributing a short essay to the catalog, trying to be thoughtful in interviews, querying editors about possible commentaries or coverage, not to mention making up titles (as above!), scanning work, and creating a database of the material.

This tiny illustration cracks me up every time. It’s mean, sure, an easy send-up of everyday modern tourist alienation from Nature. The humans are trapped in a tram (maybe like the cable car in Olympic Valley) or on a train or in a bus. But it’s also a sincere, genuine invitation, right? To be surprised, to embrace wonder?

This tiny illustration cracks me up every time. It’s mean, sure, an easy send-up of everyday modern tourist alienation from Nature. The humans are trapped in a tram (maybe like the cable car in Olympic Valley) or on a train or in a bus. But it’s also a sincere, genuine invitation, right? To be surprised, to embrace wonder?

So, here’s what I’m learning about writing and curation and biography and history and, yes, myself. Los Angeles Times columnist and my former OC Weekly editor Gustavo Arellano (A People’s Guide to Orange County) recently began his post-performance lecture at the Mark Taper Forum by admitting that before signing on as dramaturg for that legendary theater’s staged reading of The Trial of the Catonsville 9, he hadn’t even known the meaning of the word.

Dramaturg (or dramaturge): “a literary adviser or editor in a theatre, opera, or film company who researches, selects, adapts, edits, and interprets scripts, libretti, texts, and printed programs (or helps others with these tasks), consults authors, and does public relations work.”

University educated but also broadly self-taught, research-obsessed, and of course curious about everything, becoming the dramaturg for a one-night anniversary celebration performance sent Arellano to the UCLA archives, to rereading the play, to investigating the beautiful, complicated politics of the Taper’s original staging of the Danie

l Berrigan play, a theatrical adaptation of court transcripts of the famous political trial of committed anti-war activists who entered the Catonsville, Maryland draft board office, removed Selective Service files, piled them outside in the parking lot, prayed, and ignited them with home-made Napalm.

Guess what? I’ve decided that I am a dramaturg for a long-running play about Peter Carr, staged by both him and me, attended by whoever shows up, if also a character in it. Indeed, I am doing my best to curate not just an art show but a life, something short (so far) of writing a biography. God help me but require some of that same commitment and integrity and generosity and telling and retelling.

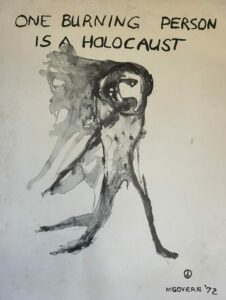

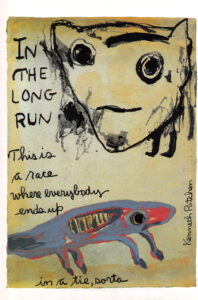

Oh, and here’s where I might quickly situate (and salute) Peter’s politics. He seems to have produced and printed his very own McGovern for President poster, one of many composed in service to campaigns including the anti-war, anti-nuclear, anti-intervention, and ecological struggles of the late sixties through his death. He also created leaflets and flyers, this one advertising a reading by a poet he admired, and whose influence on his writing seems obvious. Easy enough to see Kenneth Patchen, William Blake, Whitman, theBeats, and Ferlinghetti in Peter’s art, writing, and worldview.

Patchen, famous for his poetry and novels — and books illustrated with fairy tale creatures — wrote this, which seems to capture what Peter was up to:

“I don’t consider myself to be a painter. I think of myself as someone who has used the medium of painting in an attempt to extend – give an extra dimension to – the medium of words. It happens very often my writing with a pen is interrupted with my writing with a brush – but I think of both as writing.”

Except that maybe Peter’s drawing was interrupted, as it were, by his writing. Here’s a piece which shows one or the other, with embedded text (mantra, declaration, invitation) , an exemplary eco-scene of SoCal landscape or seascape, maybe a whale in the center, like the migrating grays which he saw from his house in South Laguna. “I fancied there were other creatures there besides me.”If I’m doing my job, perhaps you’ll read the excerpt, below, from Peter’s autobiographical, multi-voiced, prose meets paintings cri de coer, a book which adopts personae,occupies place, and projects an interpretation of the world at multiple moments as seen and lived a la Whitman, as if it were all at once. Peter published it, with illustrations, in 1974. You can hear me read the whole thing on a recent broadcast of Bibliocracy Radio, co-produced by Hunter Jones for and with the Community of Writers. Link here.

Except that maybe Peter’s drawing was interrupted, as it were, by his writing. Here’s a piece which shows one or the other, with embedded text (mantra, declaration, invitation) , an exemplary eco-scene of SoCal landscape or seascape, maybe a whale in the center, like the migrating grays which he saw from his house in South Laguna. “I fancied there were other creatures there besides me.”If I’m doing my job, perhaps you’ll read the excerpt, below, from Peter’s autobiographical, multi-voiced, prose meets paintings cri de coer, a book which adopts personae,occupies place, and projects an interpretation of the world at multiple moments as seen and lived a la Whitman, as if it were all at once. Peter published it, with illustrations, in 1974. You can hear me read the whole thing on a recent broadcast of Bibliocracy Radio, co-produced by Hunter Jones for and with the Community of Writers. Link here.

from Aliso Creek

Everybody knows that nobody wants peace. Everybody knows that everybody wants excitement and glory. Even everybody down here by the beach wants to get out of a stupid dull existence. And everybody knows that the best way to do any of all this is with a lot of money. The American system is about this.

Everybody says thoughts to people; people talk to people now that the rains have come again. They are scared of the government and run-off. High tides are dangerous. Death could happen. In the absence of official doctrine, in the light of liberty and justice for all, in the orange glare of color TV, everybody clings to scraps of paper in pants pockets, well-creased ends of torn envelopes with the words of the President written on them, “Everything is going to be OK.”

The big brown slime wipes across L.A.

Everybody watches on the tube as the planet slides into the galaxy bearing too-brief lives and much death where all this is needed by God for His Big Plan which sounds Groovy and about as Big a Thing as anyone has ever thought of.

There will come too much rain. I know it. All the hills about L.A. and even now where Salt Creek used to be that they chop and carve and burn will sink and slide slowly into the ocean. All the beautiful land will go down the rivers with all the wrecked cars, boards, plumbing fixtures, styrofoam cups, cigarette ends, and the poisonous wastes of pill-supported lives.

The fumes rise every day to greet the sun. The people do too. They say how are yuh? Maybe I won’t have to go to work today. Maybe school will be closed.

Before I came up this coast looking for money like all the other white Christian Europeans, I had devoted my life to money and enjoyment like all other white European Christians back in holy Spain. I hoped to strike it rich and moral like Henry Ford or T.A. Edison. As we were sailing along I said to Juan, Juan Cabrillo that is, look Juan, when we get there God will be on our side as usual, but in case something goes wrong we had better take some priests along. He did what I told him and we all got rich. My brother-in-law got a land-grant and they named a town, a lot of streets and a university after him. He was good and he was rich and he owned everything after the Indians were killed off. His name was Irvine.

Mission San Juan Capistrano is no longer a cattle ranch and a jail. They sell weddings there instead of pigeon food, and they charge you fifty cents to get in.

The two main features of once-holy Aliso Canyon are a golf course and a sewage disposal plant.

The rock off the coast where the spirits spoke to men is now private, of course, and is the main feature of a trailer park called Treasure Island. Across the highway is another feature — Alpha Beta Market and shopping center.

Shall I tell the truth? Am I safe enough to say it? That violence washes down the streets of the L.A. basin and finally ends up here at the sea, banging on their fancy houses by the beach where they keep everybody out who is inferior — everybody who is less than white, sun-browned, dangerous to other humans and the planet.

Can I say it in public? Can I say what happened to the cliffs where the Spaniards threw hides to the first white predators on my coastline here — where sea-otters and seals and whales and abalones lived and the men and women worshipped and played and fucked and died to the whistle of cold winds over sun-bleached sands — where the popeyed flounders groped for sea-bugs and the crayfish died their countless numberless deaths and birth into piles of seashell and skeleton?

What happened?

Jack-in-the-Box.

Here’s one which speaks for itself, with me insisting on, well, Peter insisting on it. “You must look at the ocean & the mountains & the plains & everything that grows there.”

Here’s one which speaks for itself, with me insisting on, well, Peter insisting on it. “You must look at the ocean & the mountains & the plains & everything that grows there.”

I’ve got more, much more to share, write about, preach on and, indeed, ask you to look at, per Peter’s persistent invitation. This is Peter Carr and me trying to persuade you that the work of my subject, and my own work on his behalf, is worthwhile and urgent and immortal and joyful and not to be missed. I’m an editor and a literary adviser to a project which doesn’t quite exist, after all, or maybe has always existed. Hard to tell, pun intended. Lately I’m a dramaturg doing public relations for a ghost. Wish me luck.

doing public relations for a ghost. Wish me luck.

Peter Carr | Artist for Survival October 28 – December 10, 2024

Curator Talk: Monday, October 28 at 6pm / Opening Reception: Monday, October 28, 7-9pm

Peter Carr: Artist for Survival is the first large-scale art historical retrospective of the poet, activist, and fascinating outsider artist, Peter Carr (1925-1981). Throughout his life, Carr created idiosyncratic images that were distinctly evocative and expressionistic, many of them explicitly political (he founded the Orange County chapter of Alliance for Survival) and/or inscribed with fragments of his own poetic compositions. A long-time resident of Laguna Beach, a number of the works focus on his social observations of everyday life along the California coast in the ’60s and ’70s, including his own activism against the encroachment of the nuclear and military-industrial complex into the region. For much of his professional career, Carr served as a literature professor at CSU Long Beach. Following his sudden death, more than four decades ago, his massive personal archive of drawings, paintings, and notebooks passed to his fellow activist and one-time student, Andrew Tonkovich, himself now a retired lecturer from UC Irvine and longtime editor of The Santa Monica Review. For over forty years, these works have gone largely unknown and unseen, with this major retrospective being the first time that many of these pieces will ever have been exhibited publicly.

CERRITOS COLLEGE ART GALLERY/Cerritos College

11110 Alondra Blvd Norwalk, CA 90650

Admission Free. Parking $3 in Lot 10 on 166th Street via easy online app.

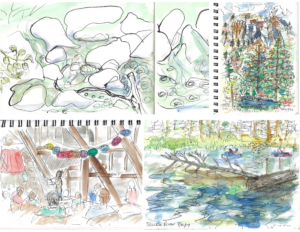

Watercolors

by Janet Fitch

HOW TO WRITE ALTERNATING PAST AND PRESENT CHAPTERS

by Shi Naseer

Set against the backdrop of China’s one-child policy, The Cry of the Silkworm follows a girl’s poignant coming of age in a Sichuan village (1990s) and her quest for vengeance against a government official in Shanghai (2002). I alternated chapters between my protagonist Chen Di’s current life as an avenger and her childhood as an unwanted girl. The chapter titles are formatted as “Shanghai, Winter 2002” and “Daci Village, Autumn 1994.” If you plan to use a similar structure for your novel, here are six steps to consider.

- Decide if you really need multiple timelines

Two full-fledged timelines can enhance themes like memory and trauma but prepare yourself for a challenge. You are basically writing two stories: both need to be compelling, and they must connect. Readers don’t always find the Present and the Past equally engaging. You also risk confusing readers, especially if you already have multiple POV characters. Imagine dual timelines on top of three POVs, i.e., six types of chapters – my head would spin!

I alternated between Present and Past chapters in The Cry of the Silkworm because the purpose of the Past is more than providing backstories for the Present. The Past has its own arc; it’s my way of exploring the one-child policy’s impact on rural China. Occasional flashbacks wouldn’t suffice to tell the full story, and Chen Di’s Past and Present are so different that presenting her life chronologically would make the book feel disjointed.

- Define the Present and the Past and determine how you stage them

Once you decide on alternating Present and Past chapters, determine their time spans and gauge how much space each should occupy in your book.

In Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens, the Past spans decades and is the main story, while the Present is mostly a courtroom scene. It therefore has snappy Present chapters, with more pages dedicated to the Past. In The Cry of the Silkworm, the Present spans only a month but details Chen Di’s revenge; the Past spans a decade and recounts her childhood and adolescence. I dedicate a comparable number of pages to both.

The Present or the Past might not unfold in traditional chapters: the Past often takes the form of letters, diary entries, etc., as in Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn.

- Find the arc in the Past and the Present

Both the Past and the Present need clear storylines with their own sets of conflicts, climaxes, and resolutions. Each requires a separate arc for your protagonist(s).

In The Cry of the Silkworm, the Past chronicles Chen Di’s life in a Sichuan village in the 1990s, where families prioritize boys, and the one-child policy is strictly enforced. She seeks education, loves and protects her little brother, and witnesses unforgettable scenes with the authorities. Then her mother dies.

The Present depicts a gutsy, aikido-practicing Chen Di, alone in Shanghai. Now twenty and hardened by experience, her determination to avenge her mother’s killer is strong, and she steels herself against affection of any kind. Then she meets a cocky, wisecracking teenage boy who reminds her of her little brother. Will he aid or hinder her plan for revenge?

Joining the Past and the Present gives the arc of the whole novel.

- Connect the Present and the Past on a small scale

Ending a Present chapter with a question about Character X or Event Y and starting a Past chapter with Character X’s name or Event Y’s details is a straightforward way to link them. In The Cry of the Silkworm, one Present chapter ends with Chen Di spotting the man she’s been hunting down, and the next Past chapter starts with the same man terrorizing her village.

Remember to weave the two timelines together through details: people, food, clothing, meaningful items, and motifs. Silkworms, of course, come up in both my timelines. Other small examples: In the Past, Chen Di was deprived of century eggs. In the Present, she gobbles one up every morning. In the Present, she’s always wearing her old-fashioned green jacket, hiding her face with the hood. In the Past, we see that the man who broke her heart gave it to her as a parting gift.

- Connect the Present and the Past on a large scale

The Present and the Past must link on the full scale of the novel. Past events must (a) explain the motivations and actions of your characters in the Present, (b) answer some of the biggest questions raised in the Present, and (c) resonate with Present events, thematically speaking.

In The Cry of the Silkworm, Chen Di’s Past shows us how she became the person she is in the Present. In particular, the Past culminates in her resolve to seek vengeance against a government official. The Present starts with her spying on the official’s workplace, waiting to spot him, trail him, and kill him.

In a thriller, the moment a Past timeline connects to the Present is often the reveal of a shocking twist. Such as in The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides, where key events are explained, and two characters become one.

- Control how much the Present should “spoil” the Past

For the Present to work, you need to give readers enough information. But if you give too much, you risk losing the tension in the Past.

In The Cry of the Silkworm, we know upfront that Chen Di is in Shanghai to seek vengeance against her mother’s killer. But we don’t know what happened to her little brother – something that haunts her to this day. Is he lost? Dead? Will he show up again? Readers form their own theories and become engaged.

You can fine-tune your chronology and structure by moving chapters and scenes during the rewrite. Ensure that the layers of revelation unfold naturally. Readers don’t want to feel like information is being deliberately withheld just to create suspense.

This article appeared originally at the Curtis Brown Creative website and is reprinted with the permission of the author.

POEM

by Hermelinda Hernandez Monjaras

Hermelinda Hernandez Monjaras, an undocumented poet of Zapotecan descent from Oaxaca, Mexico, is a 2024 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellow. Raised in Fresno, California, she holds an MFA in creative writing. She has also participated in Juan Felipe Herrera’s Laureate Lab Visual Wordist Studio and received a Community of Writers fellowship.

Hermelinda Hernandez Monjaras, an undocumented poet of Zapotecan descent from Oaxaca, Mexico, is a 2024 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellow. Raised in Fresno, California, she holds an MFA in creative writing. She has also participated in Juan Felipe Herrera’s Laureate Lab Visual Wordist Studio and received a Community of Writers fellowship.

REUNION

by Max Byrd

1

The first one he saw stepped out of the subway car two doors ahead and started for the stairs.

It was the 59th Street stop, 8:15 in the morning, and the stairway as Cushing looked up at it was a churning mob of shoulders and hats. The stranger fell in and began climbing the steps with the hectic weariness of all New Yorkers, not in the least conspicuous—average height, gray hair curling over his collar, shoulders slumped a little in what used to be called a scholar’s stoop. He wore a tan raincoat, one of those vintage coats before microfiber came in, a London Fog with the pretentious epaulettes. Cushing hadn’t seen one in years, nor had he seen an old blue and white Pan American bag like the one in the stranger’s left hand.

Where on earth had he dug that up? eBay probably, Cushing thought casually, hanging back, not yet understanding. Then as he watched, halfway up the stairs the tan raincoat began to fade and grow pale, the color of water. The gray hair flickered to near transparency. In mid-swing the Pan Am bag simply vanished, then the hand, the sleeve, the whole man vanished, as if someone had slowly raised a window curtain and let in light.

At the top of the stairs Cushing stood and looked left, right. The mob boiled up around him like a geyser. He was bumped, pushed, elbowed aside by all too solid flesh. He let himself be carried out of the current while he squinted hard at the sky—squinting seemed to help his memory these days—and tried to remember the pills he had taken at the hotel that morning, the blood pressure, the cholesterol, the anti-trembling one, the eyesight one, two or three others. At his age, he liked to joke, he just walked into the drugstore and said, “I’ll take one of everything.” Clearly, he had forgotten something, he thought, or mixed them up. He shook his head to clear it.

The visit to his cousin went as well as could be expected. She was four years younger than Cushing but had gone through more pain. Bedridden now, tended by a Puerto Rican nurse who watched him narrowly and looked as if she would count the spoons after he left. The cousin had done something in show business, administration or production, and still lived in a nice apartment close enough, she said, to smell Broadway. They talked about his flight in from Phoenix the night before, then an old family friend named Chew, who had died. When they were children, they had thought Chew was Chinese because of his name, but he was really a good old boy from Memphis with two violent felonies in his record.

At the Amtrak station Cushing found that he was early—well, he was always early, all his life—and the platform for Boston was nearly empty, a good change from the crush of the streets. At the far end of the platform a bum, as they used to call them, or a tramp or a hobo, stood leaning against a filthy wall. A poster for a circus was plastered behind him. As a boy Cushing had worked two weeks one summer for a circus passing through his little town, so maybe he had been in show business too. When he drew closer, he saw that the tramp was wearing an Army fatigue jacket and torn jeans. One knee poked out of the jeans like a knobby moon. He had stringy long hair and a dark green baseball cap with the insignia of an Army regiment. This was the second one.

“Vietnam,” the tramp said, “’sixty-seven and sixty-fucking eight,” and Cushing nodded. The man’s face looked strangely familiar.

“You go too? You look the right age, dude.”

Cushing shook his head. “No. Sorry.” And wondered why he had said Sorry. No, he knew why.

“We could have been war buddies,” the tramp said in an unreadable voice, and now Cushing saw that there was a mad look in his eyes. “Rice paddy buddies, popping anything that moved. Anything yellow that moved. Yellow blood everywhere. And the dope, man. Never had such good dope.” He spat on the platform pavement, a big unhealthy-looking blob of green mucus. He fumbled in his windbreaker and came out with a squashed pack of Winstons and Cushing was surprised because he didn’t think they made Winston cigarettes anymore. The tramp lit one with a practiced snap of thumb on match and blew smoke up at the “No Smoking” sign next to the circus poster.

“You could have been right in it wit’ me,” the tramp said, still in that unreadable voice that could have been sad or angry or simply thoughtful, musing. “But you took off somewhere else, like college or Canada, am I right? And I went off and got shot instead for my country, man, right in the kidney. I still don’t pee right. Then while I was laying there a Viet Cong stabbed me in the butt with a bayonet, see if I might be alive. But I wasn’t movin’, right then I wasn’t alive. You should have been there, man.”

Cushing was looking down the tracks. He didn’t want to look at the tramp with the Army cap and the dirty clothes and the hole in his pants. He felt in his pocket for his wallet. Ten dollars, he thought. No, twenty, the man had to eat.

But when he looked up again, the platform was empty, the tramp was gone, Cushing’s train was rocking on the tracks, coming into the station backward, as trains did nowadays.

2

The first event of the Reunion was held at a classmate’s house on the North Shore, not far from Plum Island, which indeed you could just about see from the highest part of the classmate’s lawn. Standing alone as he often did at parties, Cushing shivered in the afternoon sun. He was still brooding about the two vanished figures, hands trembling a little, though he was sure he had taken the right pill. To distract himself he tried to remember what Plum Island was like. He remembered that he had gone there once with a girl from Dedham. He remembered that the name came from the wild plum bushes near the beach and that the sand often changed colors over a day, from white to tan to plum (of course). What had happened to that girl? What life was she living now? Plum Island had been on maps since 1614. He blinked and thought people don’t appear and disappear like ghosts.

“I heard a funny one.” This was another classmate named—thank God for name tags—Grier, who had wandered over from the bar at the other end of the lawn, near the house. “You know the three ages of man?”

Cushing smiled and shook his head.

“Youth, middle age, and ‘You’re looking good!’” Grier grinned and Cushing flinched at the obligatory punch on the shoulder. Despite his delicate name, Grier had played on the football team and the year after graduation finagled a tryout with the Cincinnati Bengals, which he failed. Cushing hadn’t done any sports. Grier’s punch had hurt, Grier’s handshake was firm. No ghost. Cushing decided to risk another whiskey sour, the preferred drink of his college years, which he would order to impress girls from Wellesley, who were not usually impressed enough.

The bar was just a long utility table, tended by undergraduates wearing blue and white vests, the college colors. Cushing chose the corner by the clay tennis court—the classmate had done very well—and was turning away with his whiskey sour when a woman took his arm and pressed it against the side of her breast. “Brenda” or “Linda”—her nametag seemed to blur.

“Jimmy Cushing! You haven’t come to one of these for years. I hoped you’d be here! I wanted you to be here!”

She had the yellowy breath of a white wine drinker and she pulled Cushing even closer, as if to show that the breast press was not a mistake. People noticed, some snickered. She leaned in for what Cushing’s show business cousin would have called a ‘smackeroo,’ and Cushing, who was not without humor, smiled at Grier watching nearby, and told her, “You’re looking good!”

“I’m very drunk,” Brenda said (he had decided on Brenda) and pulled him toward a bench beside the tennis court. “Tell me everything,” Brenda said. “I want to hear everything! Where do you live now? Are you still married? Oh, right, divorced, I knew that, ‘Mr. Bachelor Man.’ Well, I’m a mess, God, Jimmy, I want to hear everything. Don’t you wish we could go off and talk all night?”

She was still pressing his arm against her breast, her left breast, and classmates were staring. She pressed it harder, up and down. I’m getting to second base at my goddam college reunion, Cushing thought. “Do you remember when we dated?” Brenda said, although now he was beginning to think her name was Amanda. “And I wouldn’t let you do it?”

“I don’t think—” Cushing began.

Brenda spilled a little white wine on her dress and leaned over unsteadily to kiss him on the cheek again. “We should have stayed together,” she said. “We would have been so good together. You were always the smart one, smarter than Lyman was, that prick. Remember how we used to go into Boston for plays and we talked about how you’d go to law school and we’d live in Brookline, in a jolly corner. Jimmy, I wish we could start over, I wish we could have lived in Brookline. ‘Of all sad words,’” she recited mournfully, “something, something, it might have been.’”

There was more about their not doing it, and Cushing nodded and drank his whiskey sour and thought, I don’t remember any of this. We never dated. We never went to Boston or talked about Brookline. She went out with Lyman Hobbes, who was a math whiz, and they got married after graduation. I barely knew her. I would remember her boobs, he thought. I have a good memory for boobs.

This made him chuckle and he stood up to go to the bar again. When he came back with his third whiskey sour, he didn’t see her right away and despite the alcohol his face went cold with fear. Another one? Why were people disappearing?

Then he picked her out over at the end of the lawn, talking to someone else. He should stop drinking, he thought. But even as he watched, Brenda-Amanda began to grow hazy, indistinct, though maybe that was just the sea mist blowing in from Plum Island. He should at least cut back, he thought. But he took another swallow and thought that a better question was why were people appearing? He didn’t believe in ghosts. Nobody believed in ghosts.

The dinner was on the lawn. Four long tables with white cloths, set up for twenty at a time, under strings of colored lights—theirs was a small college; eighty was a good turnout. The Committee had ordered roast beef for the carnivores and huge salads for the vegetarians. Cushing got the salad by mistake, but it didn’t matter. He switched to Sam Adams beer and listened to shrieks of laughter and the jokes and the high-pitched questions buzzing up and down the table, and eventually they came round to him. Yes, he still lived in Arizona. Yes, he still taught American history in high school. No, nobody since his divorce. Yes, ten years was a long time. His son lived in Taiwan, doing tech stuff. No, he didn’t see him that much. Arizona was fine; the summers weren’t really that hot.

“We all thought you’d be a lawyer.” An owlish classmate named Henry leaned across the table, all eyebrows and elbows. Henry sold real estate in Poughkeepsie. “Or some kind of judge.”

“He got the best grades,” Cushing’s neighbor told the table with a hint of disapproval in his voice. This neighbor was an orthopedic surgeon. “Best grades in the class,” he repeated, “our Jimmy. He wrote the Class Ode.”

“Class ‘Odor,’” a Roast Beef snickered.

“I thought you’d live in New York and be a professor or a writer.” This was bleached-out Linette, pale as air. She had dated one of his roommates but always looked in a certain way at Cushing.

“He was a total grind,” Henry informed his wife, who was picking at her salad, bored. “He practically haunted the goddamn library.” Then earnestly, “You should have played football, Jimmy.”

Cushing stared down at the table. His eyes filled with tears. “You should have been a lawyer,” somebody said. Why would they tell him this, he thought, when it was too late? He made a sudden violent motion like someone beating away a swarm of insects. Then a woman’s voice. “Leave him alone, you!”

3

The next morning, he skipped the panels and symposia and ceremonies for the graduating seniors and the reunion classes. By the time he pulled into the parking lot next to the gym, it was already afternoon and the sea mist had returned, prowling farther inland than yesterday, brushing its fingers against the leaves of the ash trees lining the paths, whispering against the classroom windows.

Cushing wandered for a time, enjoying the crowd, the spectacle of flags and pennants and big blue and white banners draped everywhere. The biggest banner hung over the library steps and announced the Senior Theme in great blue letters: “POSSIBILITIES.” Just before six, as people were starting for their various dinners, the football band burst onto the college quad and started to high step chaotically among the seniors and their parents, blaring school fight songs as the mood struck.

From the steps of the History Building, he watched the band form a long blue snake (with white plumes on their hats), followed by exuberant new graduates cheering to a wildly disordered version of the “Bunny Hop.” In the doorway an older man, obviously a professor, stood with his briefcase in hand watching. “Hell of a lot of noise,” he said.

“I think I took your class, sir,” Cushing said. “Nineteenth-Century American history.”

“You think?”

“No, no, I did take it.”

The professor glanced at Cushing’s name tag. “Don’t remember you,” he said. “Was I any good?” Then without waiting for an answer. “Never mind.”

The bunny-hopping crowd curled around the end of the quad and lurched toward one of the arching gates that led to the dormitories. “Possibilities,” the professor said. “Look at them, possibilities-–kids marching off to be bankers, actors, doctors, everything possible. You know, during the Civil War, Grant would sometimes watch his troops go by and wonder what would happen if somebody could put a ribbon on the caps of the ones who were going to die that day. What if—”

“Realtors,” Cushing interrupted. “Judges, orthopedic surgeons, veterans, bums.” The professor raised an eyebrow. “School teachers,” Cushing said to his own immense surprise. For a long moment neither man spoke.

“You know why I teach history?” the professor asked quietly.

Cushing didn’t care. He listened to the invisible band, marching away, leaving all possibilities behind.

“That way, you lead more lives than one,” the professor said.

Cushing said nothing. As he expected, the professor had vanished. Now the music faded, too, the college fell empty. He found a bench and sat down while the ghosts swam slowly toward him, floating out of the silver-gray sea mist, a thousand mirrors, a thousand vanishing faces. Wayward and flickering existences, petals on a wet bough, dissolving and dwindling, closing to a single point. Leave him alone, you.

ABOLITIONISTA! TRIBUTE

by Steve Sosuyev

Thomas Estler—1997 Fiction participant and Community of Writers volunteer for many years—was honored in October with the 2023 Motif Lifetime Achievement Award, in recognition of his Abolitionista books and workshops—devoted to the abolition of the secretive slavery that is the sexual trafficking of children.

Thomas Estler—1997 Fiction participant and Community of Writers volunteer for many years—was honored in October with the 2023 Motif Lifetime Achievement Award, in recognition of his Abolitionista books and workshops—devoted to the abolition of the secretive slavery that is the sexual trafficking of children.

When a colleague succeeds spectacularly, such as by winning a globally recognized lifetime achievement award—in this case, the World’s Highest Honor for Child Advocacy—we might be tempted to say, “I’m so proud of you.” And we catch ourselves. What have I done to be so proud of? At most, I have the right to say “I’m so pleased for you.” Well, when Thomas and I discussed this on the afternoon before the Awards Ceremony, walking to Carnegie Hall with our freshly pressed tuxedos on hangers, he reminded me that, in 2010, when he first told me of his idea for a comic book about human trafficking, I encouraged him and asked lots of skeptical questions—which, he assures me, helped him realize his vision for a comic book, in Japanese Manga format, enormously popular with American kids, that would engage young people with a suspenseful story while educating them to protect themselves and their friends.

And I did design and edit the first Abolitionista! book in 2010, and the second in 2012, and the third and the fourth—well, I jumped on board, but Thomas was the one with the vision, and I was the one with software for fashioning books.

Thomas received his award after all of the other honorees on that October evening. Among the many illustrious recipients he gave, by far, in this reporter’s opinion, the most passionate speech—spontaneous, energetic, and personal, rendered without notes or pauses. Thomas focused on protecting children, and revealed new challenges arising today because of sophisticated technology that allows perpetrators to recruit youngsters into the pornography industry a few blocks from their homes, lured into activities that they isolate them and sometimes lead them to suicide.

No one in the evening’s program had acknowledged the New Jersey Youth Orchestra, who played throughout the ceremony. Before concluding his remarks, Thomas took a moment to thank these musicians; he had learned the conductor’s name, and he introduced her. The audience went nuts because we had been wondering, Who are those marvelous musicians?

musicians; he had learned the conductor’s name, and he introduced her. The audience went nuts because we had been wondering, Who are those marvelous musicians?

For several years, Thomas has served as the Director of Education and Creative Projects for Saving Jane, Inc., a New York nonprofit that enlisted him after they saw his first book. He has become a guiding light for survivors, with the popular workshops that he conducts in the New York City public schools.

Hosting the Carnegie Hall ceremony was Matt Vogel, a seven-time Emmy-Award winner and celebrated Sesame Street Muppet performer, widely recognized for his iconic role as Big Bird. Among the ten honorees at the Carnegie Hall event were Dr. James R. Downing, the CEO and President of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and Amina J. Mohammed, the Deputy Secretary-General of the United Nations and Chair of the United Nations Sustainable Development Group.

Past recipients of Motif Awards have included Dr. Lloyd Morrisett, the Founder of Sesame Street, and Gene Wilder, who accepted the 2013 Motif Global Humanitarian Medal of Honor in memoriam of Theodor “Dr. Seuss” Geisel.

The Motif Awards is committed to the universal ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the fulfillment of the Millennium Development Goals, Education for All, and many other causes supporting the education and well-being of children. Motif Awards holds consultative status with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Steve Susoyev is a graduate of UCLA Law School and has written extensively for the legal community on the child-custody rights of gay and lesbian parents and other human rights issues. His reviews and articles have recently appeared in the Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide and The White Crane Journal. In 2007 his imprint, Moving Finger Press, released his Return to the Caffe Cino, an anthology of revolutionary off-off Broadway plays that won that year’s Lambda Literary Foundation book award for drama.

EISENBERG MOMENTS

by Eugenie Montague

What do you read for? This is a question I first asked a student who had signed up for a course on creative writing but found themselves intimidated when time came to write an actual story. As so often happens, trying to articulate something useful to a student turned out to be rather clarifying for me—and hopefully the student. Like most people, I read for many things, but I have found this to be a productive question over the years, both inside and outside of a classroom. Do I read for plot? Or character? Or language? To experience surprise? To inhabit a new world? To feel invested? To feel seen? To see others, or to see the world? Is one element more important than another? Would I forgive a lack of one for a surfeit of the other? Does it depend on the book, or my mood? Fill in the blank: I would follow a book anywhere as long as____________.

In that class long ago, as an example of what a person might read for, I explained that I read, in large part, for the Eisenberg moments. Sure, I get sucked into plots; I fall in love with characters; I love structure and I have a running list of sentences so beautiful I want to get them tattooed on my body—but a large part of what I read for are the moments in a book where I feel like I have never read a truer sentence and, just for a moment, the world or something in it comes into brilliant, destabilizing focus.

I call them Eisenberg moments because of a line from Deborah Eisenberg’s A Lesson in Traveling Light. A young woman is going on a road trip with her boyfriend, though she knows at some level she has already lost him. They stay with some of his old friends and, when she meets the girlfriend of the other couple, she describes her this way: “Natalie must have been just about my age, but there might be an infinite number of ways to be twenty….” That line stopped me in my tracks when I first read it; the fog cleared; I saw into the dark spaces. Turns out, Eisenberg spoke about coming across moments like these in books: “You know how it feels when you read something that opens up a little sealed envelope in your brain. It’s a letter from yourself, but it’s been delivered by somebody else, a writer.” To me, reading these sentences or phrases or paragraphs feels like the world shifting, but (unsurprisingly) I think Eisenberg’s description is better: It’s happening inside me; I’ve been changed, my mind is altered.

I think the temporal element of the Eisenberg moment is important too. These are lines that make me pause. Sometimes, I pause simply to savor the experience of breaking the seal on that envelope. But sometimes the defamiliarizing elements of these sentences or phrases are causing reverberations that I have to sit with, allow to play out.

An Eisenberg moment can be a physical description of a character, like this from Brad Watson: “He could’ve been somebody I knew, maybe somebody I’d gone to school with, his face just now starting to beef out under the jaw with his wife’s cooking, and his eyes more tired than hard or cold but looking as if they didn’t have a whole lot of humor left in them.” Or a physical description of what it feels like to hear music, by Cristina Rivera Garza: “Their spines responding first, almost subconsciously, to the beat, and only after to the melody.”

Or it might be a description of a more nebulous emotion, like this from Alexander Chee: “Envy is like, the skin you’re in burns. And the salve is someone else’s skin.” Or this from Rosa Alcalá: “You lived with the body. There was no room for the book. You lived with the book, and the body broke a window trying to get in.”

It can be a seemingly offhand thing a character says that brings them into almost painful relief (and with them, others, the world). From Michael Bible: “Also, it seems strange to say it, but that was the first time I remember anyone telling me they were sorry.” Or a few lines of laugh-out-loud dialogue that bring the same painful clarity to the place we live in, as done by Kathy Acker:

‘Listen. This city’s about to collapse. The planet-country-empires are destroying New York (us): they’re sending Z-bombs to attack our intestines and hearts, heart attacks; they’re causing the huge pathways of the city like giant snakes to turn on themselves, make people go crazy on the streets, make people have to take increasing dosages of speed-junk, make people murder, sexually assault.”

“It’s just some guys have too much money.”’

An Eisenberg moment can be only a few words, like this fragment of two lines from Morgan Parker: “Blurry/ princess, self-narrating.” Or almost half a page as this description from Anuk Arudpragasam’s protagonist about what it felt like to sit and talk with his friends before the war:

An Eisenberg moment can be only a few words, like this fragment of two lines from Morgan Parker: “Blurry/ princess, self-narrating.” Or almost half a page as this description from Anuk Arudpragasam’s protagonist about what it felt like to sit and talk with his friends before the war:

“What they spoke about at such times he could no longer say, but there were moments, Dinesh could remember, when their conversations would begin to slow down, when everything they said would seem to circle around some strangely intangible object, around a place or thing they could sense in the vicinity even if it couldn’t be seen. All their questions, answers, pauses, and responses, all their additions, hesitations and elaborations, each and every utterance they made at such times felt like a delicate attempt to move closer to this object, so that tentatively, intuitively, stopping and starting, their conversation would seem to spiral around this sensed but unseen place or thing, drawing closer and closer to it, moving more carefully and more nervously as smaller and smaller circles were drawn round it, till finally, with much apprehension, each of them fully absorbed in what was going on, something was said that could not possibly get nearer to what they sought. When such a point was reached they were able to sense it almost instinctively, even if they couldn’t see or touch what they had found, as though what they had been searching for all along was not so much a place or a thing as a mood, a mood which had been obscurely understood from the very beginning as a means by which they could come together, by which they might move out of their own separate worlds, onto a plane in which they could recognize and understand each other fully for a brief time.”

I could go on for ages with examples, of course; I have books where almost every page is dog-eared or underlined. But I’ll end with an Eisenberg moment that encapsulates what it feels like when I read an Eisenberg moment, this one by William Trevor: “Rain has sweetened the breathless air, the angel comes mysteriously also.”[1]

[1] Brad Watson, Dying for Dolly (There is Happiness: New and Selected Stories); Cristina Rivera Garza (translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Aviva Kana), The Taiga Syndrome; Rosa Alcalá, You, the Body & the Book) (You); Alexander Chee, Edinburgh; Michael Bible, The Ancient Hours; Kathy Acker, Rip-Off Red, Girl Detective; Morgan Parker Black Woman with Chicken, (There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé); Anuk Arudpragasam, The Story of a Brief Marriage; William Trevor, After Rain (After Rain)

Eugenie Montague received her MFA in fiction from the University of California, Irvine. Her short fiction has been published by NPR, Mid-American Review, Faultline, Fiction Southeast, Amazon and Flash Friday, a flash-fiction series from Tin House and the Guardian Books Network, and was selected by Amy Hempel for The Best Small Fictions (2017). She currently lives in El Paso, Texas with her family. Her debut novel, Swallow the Ghost, was published by Mulholland Books in August 2024.

FOUR POEMS

by Ruben Quesada

UNCONSOLED

by David L. Ulin

Last night, I dreamt that I was flying. I was in a city, perhaps New York or perhaps Los Angeles, although in actuality it was neither. Still, I had the sense I had been here before. Perhaps it is a place in the landscape of my dreaming, a metropolis of my imagination. Perhaps it is somewhere I visited once and then forgot. In any case, the flying: I was on a coastal highway, which was also densely urbanized, tall buildings and bus traffic, soot and smoke and sand and air. There were lampposts and empty lots and the apartment in which I was staying: a large, blank zone of the interior where I could not find my bearings, could not find my way out. Then, with neither warning nor transition, I found myself outside, moving through the air like a swimmer, dipping and spinning, twirling, thirty or so feet above the surface of the road. I was conscious enough to remember that I suffer from acrophobia, from vertigo, and yet that quickly faded. I was subsumed with the touch of grace. I want to be clear about this; I was not disembodied. I remained aware that at any moment, I would have to land. But in those seconds of suspension, I felt freed of something. I felt as if, for this instant in any case, I had been released.

And why not? Dreams of flying, a quick Google search indicates, signify both possibility and the desire for escape. Certainly, both would apply to me. Over the last three years, the largest part of my attention has been directed toward the care of my parents, and most recently to the final illness of my mother, who died three weeks ago pretty much exactly to the minute, her mind and body diminished by dementia and carcinoma. I saw her on the morning of the day she died, and as has become my custom, I took a slew of photographs. Those final images — of her sitting on the couch at the assisted living, in the same clothes that, six hours later, I would see on her corpse — affirm for me a thought I had not previously recognized might be consoling: that we are ourselves and living until the last second of our breathing, that even in our dying, we continue … until we do not. This is something I will remember, although if I’m being honest I cannot tell you if it settles me or not.

Consolation can be like that. It is not a two dimensional affair. Like grief, it has teeth and claws and requires us to cast off the veils of so-called daily life, to expose the irreconcilable contradictions underneath. For much of the time I have been caring for my parents, I’ve written about the experience. Written and read about it too. Not so much because I think it will ease my heart (it doesn’t) but because it allows me to keep track of where I am, where we all are. This is a form of consolation also, this pursuit of clarity, which has for me almost everything to do with witness. I think of the opening sentences of Albert Camus’s The Stranger: “Maman died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” I think of Annie Ernaux, nearly half a century later, echoing Camus in A Woman’s Story: “My mother died on Monday 7 April,” she begins. Something similar applies in the writing I am doing, which is largely poetry, often composed on the fly, on my phone when I am walking, which is how I am writing these notes as well. There’s something about walking, as, perhaps, there is about flying. Consolation, again, or the intercession of a mercy of a kind. So, too, the poems, which arrive at no conclusion. Or maybe it’s that I already understand the conclusion, after all.

No, what I am writing are a set of distillations, not quite snapshots (most are too long to fit that label) but what let’s call testimony or accounting, a record of events. Memory, in other words — brief encounters, visits to the doctor, snippets of conversation, the weight of loss. This is not writing as cenotaph or monument; it feels too immediate for that. Nor is it a matter of preservation either, in a situation where ultimately nothing will be preserved. I’ve come to think of it as innate, intrinsic, poetry as a necessary gesture, a way to offer consolation to myself.

That consolation emerges not only in the content but also in the container. Like Cash in William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, who carpenters his mother’s coffin into shape where she can see him, I am working in plain sight. And like Cash as well, I feel something restorative in such a process, although I remain trepidatious about the implications of that word. All the same, as I immerse in shape, in structure — line length, stanza format, the precision of word choice — my attention is returned to me. The experience reminds me of my dream last night, the way that as I lay flying, in the act of it, I could feel my fear of heights dissolve. The only other time I remember flying in a dream I was four years old, and the dream involved my death. I am much older than four now, but that is no longer what’s at stake. Rather, in the face of my parents’ deaths, hers already behind us and his looming somewhere ahead, I feel the need to bear witness, to stare directly into the center of each moment, as if I were tracking the passage of an eclipse.

Or perhaps my dream suggests a more useful metaphor: flying without a net.

David L. Ulin is the author, most recently, of the novel Thirteen Question Method. His other books include Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay; The Lost Art of Reading: Books and Resistance in a Troubled Time; and Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology, which won a California Book Award. He is the book editor at Alta and the former book editor and book critic of the Los Angeles Times. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The New York Times, Harper’s, The Paris Review, and The Best American Essays 2020. The recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, and Ucross Foundation, as well as a COLA Individual Master Artist Grant from the City of Los Angeles, he is a Professor of English at the University of Southern California, where he edits the journal Air/Light.

WRITING A MEMOIR IS NOT THE THING THAT HEALS YOU

by Gina DeMillo Wagner

The question came up at every bookstore reading, during podcast interviews, and at media appearances.

“Was it healing to write?”

It, my memoir, Forces of Nature, takes place in the aftermath of my brother’s sudden death and follows my quest for answers about him, about the nature of grief, the limits of caregiving, and the forces that shape our sense of family and home.

Writing the memoir taught me that every question is hiding other questions. And so, as I looked at the faces of readers asking me, “Was it cathartic to write this? Do you feel better now?” I saw their bodies vibrating with their own family secrets, their unexamined pain. In questioning me, what they really wanted to know was whether writing a memoir could heal them too.

The answer is no. Not because I’m broken or because the book failed me in some way, but because healing was never the objective of my memoir. Nor do I believe it should be the objective of theirs (or yours).

It’s a misconception that writing about our grief and trauma is the thing that will cure us, that getting it all out will not only make visible your pain but transmute it somehow. This is magical thinking, an idea perpetuated by well-meaning life coaches and social media gurus and high school English teachers.

I’m not saying writing isn’t beneficial. I have a stack of journals at home, packed margin-to-margin with words that I hope no one ever reads. I write first thing in the morning, before my inner critic comes online. The effusive nature of this practice is a form of meditation. It clears my mind and helps me develop self-compassion.

But a memoir is different. It’s a book. A volume of work, crafted for public consumption. A memoir evokes the writer’s experience for the reader. It not only documents the past, but it confronts it. If a journal holds the unedited, myopic runoff of our psyche, then the memoir renders it into something communal and useful.

The work of a memoir author is to examine time and memory, to compress it or layer it, maybe rearrange it, to find echoes and points of resonance, like holding a prism up to the light and tilting it until you see what colors hold true. There’s no prerequisite that the memoir author be healed or unhealed, that they have all the answers or none. They only need to be human, honest, willing to show us how their story is actually everyone’s story. They connect the dots between the personal and the universal.

The other problem I have with this question is that I think we sometimes conflate healing with acceptance or an absence of pain. I know I’m not the first to caution: Writing a memoir won’t make anyone love you or apologize to you. It won’t satisfy your craving for revenge. It won’t mend a strained relationship. It won’t exorcise the trauma from your body. It won’t bring anyone back from the dead. It won’t inoculate you against further grief.

If you’re writing for catharsis, buy a journal. If you’re writing to create a mirror or portal or an offering – to your readers, through time, or to your younger self – write the memoir.

In my experience, healing is kaleidoscopic, dynamic, complex. It happens in relationship to ourselves and to others. It comes as much from reading as writing. It requires social support. Witnessing others as a way of witnessing ourselves. Interrogating our lives in the context of the systems that formed us.

Want to know how I found enough peace to write my story? It happened off the page.

It happened in my therapist’s office where I first examined the secrets I kept from myself. It happened at 3 AM, when I’d meet up with my brother in my dreams. It happened in my car, singing along to the radio and weeping. It happened over coffee with friends. It happened on mountain trails, my footsteps and breath mixing with the wind and coming back to me in birdsong. It happened on massage tables. It happened in art galleries, at libraries, in movie theaters. It happened face down in a swimming pool, bits of grief and anger falling out of my mouth with every stroke, dissolving in my wake. It happened surrounded by my partner and children, my family of choice.

It’s still happening. Perhaps in that way writing is like healing. It never feels done.

Gina DeMillo Wagner is an award-winning journalist and author of the memoir, Forces of Nature. Her writing has been featured in The New York Times, Washington Post, Memoir Magazine, Modern Loss, Outside, Writer’s Digest, and other publications. She is a Yaddo Fellow, a winner of the CRAFT Creative Nonfiction Award, and her memoir was longlisted for the 2022 SFWP Literary prize. Gina has a master’s degree in journalism and is an instructor at Lighthouse Writers Workshop in Denver. Follow her @ginadwagner or ginadwagner.com

ABOUT THE OGQ

Omnium Gatherum Quarterly (OGQ) is an invitational online quarterly magazine of prose and poetry, founded in 2019 as part of the 50th Anniversary of the Community of Writers. OGQ seeks to feature works first written in, found during, or inspired by the week in the valley. Only work selected from our alums and teaching staff will appear here. Conceived and edited by Andrew Tonkovich. Submissions will not be considered.