It’s Not Easy to Write About the Big Easy: A Craft Talk on Place

by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

You may know that my two books take place in New Orleans, my hometown, and though I’ve come to rely on the city of New Orleans as a setting, I didn’t always know I was going to write about my birth city. I resisted it for a long time. Today I want to talk about my journey to claiming that place; I’m going to talk about the ways I try to convey the details of my home in my work, and I’m going to talk about ways other authors have done the same.

I said I was resistant to writing about New Orleans, and that’s true— in fact, my first book which was never published took place in the Dominican Republic. I went to the Dominican Republic after college to work for this non-profit organization that helps Dominicans of Haitian descent secure citizenship rights. I also went to write a book. The book was about an African American girl from New Orleans who goes to the Dominican Republic to help a struggling community (so incredibly inventive in terms of plot, I know). While I was there, I soaked up all the details of the place, of course, because the place was new to me, and because I valued the experience. But I also paid special attention to my surroundings so I could include the details of the setting in my book. In that way, the novel was saturated with descriptions of the country’s music, spiritual practices, food, dance, language, and its political and racial divide.

I finished the first draft of the book, and it was just fine; it was a first book. At the same time, I didn’t enjoy being in the Dominican Republic for various reasons and didn’t enjoy the year overall. Because the book was less than great, and because the experience was difficult, I came to the conclusion that writing wasn’t for me. I decided to become a lawyer. I won’t bore you with the story of how little I enjoyed law school or of my bully of a boss once I started practicing, but suffice to say I left my law firm after a few years and was suddenly in a position to write again.

I returned to the book about the Dominican Republic but at this point it had been seven years since I’d lived in the place, and I wasn’t in a position to go back. To compensate, I consulted my notes feverishly; I contacted friends still there to refine some of the details and to verify others: different sayings, what certain foods smelled like, how much it cost to ride a guagua. I made a connection with someone I didn’t know previously, a Dominican of Haitian descent, and I would send him drafts and he would tell me about community aphorisms or customs and verify if I had referenced his country authentically. Even with that effort though, I never actually felt authentic. Toni Morrison said that people need permission to be writers, and it was difficult for me to access that permission because I wasn’t writing about a place that was home, and I wasn’t in the place to do on the ground research. This is not to say that you can’t write about places that are not your home. That’s absolutely not the case and I’ll touch on that some at the end of this talk. But at this stage, I’m talking about the sense of comfort that comes from writing about somewhere that you know on a visceral level.

I worked on the Dominican Republic book for a year and a half. At that point, I got an agent, but ultimately, she couldn’t sell the book, and we parted ways. After a few months, I met a woman, Jane Vandenburgh, who was leading this yearlong narrative program. The idea was that a writer would send her 30 pages or so a month, she would provide feedback, and by the end of the year the writer would have finished a manuscript. I was hesitant to join the program at first because I considered my Dominican Republic book to be my breakout book. It didn’t seem to make sense to write another one. Still, I realized that I didn’t have an agent anymore; interest in my manuscript was waning, and anyway, I’d always had this idea about three generations of a Black family in New Orleans. Ultimately, I decided I would just work on this new book about New Orleans on the side while I mainly continued to pursue publication.

I started out with that intention, but the new book took over; it began to pour out of me like it had only been waiting for a vessel. I wrote it with ease and conviction and an unprecedented sense of authority. Because I had grown up with the subject. It was my home. I knew what people ate, how they spoke, how they celebrated and how they mourned. And if there were something I didn’t know, I knew someone credible I could just call on the phone to ask.

Having said that, I was also incredibly nervous to write about New Orleans. So many friends and family would have been unforgiving if I’d gotten something wrong. New Orleanians are very, very protective of their city, justifiably so as the city is often misrepresented. The pressure to get it right forced me to learn how to present the city in a way that would honor its richness and depth in a nuanced fashion. Below, I’m going to lay out some of the tools I used to present this place in all its glory.

First, I tried to present setting through an intimate portrait of details, things you wouldn’t know if you didn’t live there. On the first page of my first published novel, A Kind of Freedom, I wrote that Ruby, the main character’s sister, has a hard time with Mondays because she has a tendency to overeat, and on Monday, her mother makes red beans and rice, her favorite food. (1). Well, if you’re from New Orleans you know that everyone cooks red beans and rice on Monday. It’s a tradition that dates back to the 18th century, when housekeepers and housewives used ham bones from Sunday supper to season beans. Monday was laundry day, and they could be busy completing that task while the beans essentially cooked themselves.

Likewise, in Eudora Welty’s The Optimist’s Daughter, the main character’s father dies in New Orleans during Mardi Gras. The author provides more unknown details of New Orleans, for instance, how slowly traffic moves through the streets of New Orleans during carnival; how people dress: one man in a skeleton and his date in a long white dress with snakes for hair, all the while a band plays, the unmistakable sound of thousands of people blundering. (35). Typically, the city is presented through cliches about Bourbon Street or vague examples of voodoo, and these more nuanced details help to convey it more wholly.

Another way to describe setting is by conveying the place through characters’ eyes. Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory is set in Haiti and in the early part at least recounts the main character’s childhood. The author, instead of just giving us a block description of a Haitian fixture, relays the setting through a major character’s eyes, in this case the main character’s aunt. “Whenever she was sad, Tante Atie would talk about the sugar cane fields, where she and my mother practically lived when they were children. They saw people die there from sunstroke every day. Tante Atie said that, one day while they were all working together, her father—my grandfather—stopped to wipe his forehead, leaned forward, and died. My grandmother took the body in her arms and tried to scream the life back into it. They all kept screaming and hollering, as my grandmother’s tears bathed the corpse’s face. Nothing would bring my grandfather back.” (3). This personal and deep description of the sugarcane fields holds more weight because it is captured through a major character’s grief.

Another way to describe setting is through relationships, through community. For instance, in De’Shawn Charles Winslow’s In West Mills, a book about a community in a small North Carolina town spanning the 1940s to the 1980s, a lot of the description of the town is gleaned through the relationships between the people in it. In the novel, everyone’s related if not by blood then by connection. The main character is named Knot. And “[w]hen the weekend came, [Knot] [would walk] down the lane—two houses to the left of her house—to tell her good friend Otis Lee Loving all about her newfound freedom. And since Knot visited him most Saturday mornings, and knew he would be in the kitchen, she didn’t bother knocking. (4-5). Likewise…“[w]hen the sun went down, Knot dressed up and bundled up. She walked the short distance—less than a quarter mile—to the dead end of Antioch Lane, to Miss Goldie’s bar house juke joint, where Knot knew people would be throwing away the money they should have been saving to buy their Christmas hams if they didn’t have a hog of their own.”(11-12). These descriptions make it clear that this is a small town where everyone knows everyone, not only them, but their finances. There’s only one place to go at night and you can reach the place by foot. There’s no need to lock the doors because you know who’s coming and when they’ll arrive. The relationships tell the story of this place better than a rote description of it could.

Similarly, in Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, a book about a cast of characters in a coastal town of Maine, you get a feel for the small town through the characters’ interactions in their local pharmacy. “Standing in the back, with the drawers and rows of pills, Henry [the local pharmacist] was cheerful when the phone began to ring, cheerful when Mrs. Merriman came for her blood pressure medicine, or old Cliff Mott arrived for his digitalis, cheerful when he prepared the Valium for Rachel Jones, whose husband ran off the night their baby was born. It was Henry’s nature to listen, and many times during the week he would say, ‘Gosh, I’m awful sorry to hear that,’ or ‘Say, isn’t that something?’” (4). Most of us don’t have that kind of relationship with our pharmacists. I certainly don’t, and the fact that Henry is on such familiar terms with nearly all his customers shows us how tightknit this community is without it having to be explicitly said.

Another way to describe setting is through describing an emotional state. In Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place, a story of several distinct Black women and their experiences with community in a decrepit apartment building on a dead-end street, the place is often described in association with the emotional state of its inhabitants. In this way, the place is not only seen but felt. For instance, “Brewster had given what it could—all it could—to its ‘Afric’ children, and there was just no more. So it had to watch, dying but not dead, as they packed up the remnants of their dreams and left—some to the arms of a world that they would have to pry open to take them, most to inherit another aging street and the privilege of clinging to its decay. And Brewster Place is abandoned, the living smells worn thin by seasons of winds, the grime and dirt blanketing it in an anonymous shroud. Only waiting for death, which is a second behind the expiration of its spirit in the minds of its children.”(191).

The final way I’ll discuss to describe setting is as a commentary: Lot is a collection of short stories that takes place in various Houston neighborhoods. In it, Bryan Washington writes: “East End in the evening is a bottle of noise, with the strays scaling the fences and the viejos garbling on porches, and their wives talking shit in their kitchens on Wayland, sucking up all the air, swallowing everyone’s voices whole, bubbling under the bass booming halfway down Dowling. But with the blancos moving in the whole block’s a little quieter now. You’ve got these dinnertime voices leaking in through the windows. You hear dishes clinking just like in the commercials. It all feels impossible to me, this shit no one I know could afford, but Ma called it cyclical. She said you have things and then you don’t.” (191-192).

In my second novel, The Revisioners, a main character describes her mother’s neighborhood: “I pull onto her block. She rented an apartment uptown after Katrina, then once she’d gutted all the walls, and replaced the roof on her old house in the Treme, she insisted on going back. Home, she’d said. Nothing like it, though her block is all white now, mostly transplants. There’s still Miss Brown and Mr. Davilier on either side of her, but every other house is a short-term rental, and even Miss Brown is considering selling to developers.” (50). These books pass subtle commentary on gentrification through the eyes of their characters, deepening the reader’s experience by providing a critical lens.

I’m finishing my third book now, and for the first time, I’m writing a novel that takes place in San Francisco. As I’ve said, I’m from New Orleans and have stuck to that place as a setting, but I’ve lived in the Bay Area for 15 years and finally feel comfortable pivoting. In preparation for writing a book in a place I don’t know as thoroughly, I’ve talked to authors who have done the same.

One such author is Jami Attenberg, who moved to New Orleans many years ago, and set her book All This Could Be Yours there. She advised the following based on her recent experience. She recommends examining our own intentions for writing a particular story outside our comfort zones. She recommends exploring—getting recommendations from people who actually live there, listening to local radio stations, watching local news, sitting in dive bars and eavesdropping on conversation, listening to the way people speak, turns of phrases. Then she advises asking for help, confirming that our interpretations are correct. I think she got it right. There’s a particular passage in All This Could Be Yours that gives me chills in its precision. Sharon, a character from New Orleans, notes that “There had been a small second-line for her father when he passed. All the neighborhood ladies had been there. Dressed. The respect Sharon felt that day for her father made her shiver. Tamara flew out for it from DC, and marveled at the public display of grief, while slipping her number to the trombone player in the second-line band. ‘Y’all know how to mourn,’ she said.” (263).

I cherish Jami’s advice especially as I dive into my next project, and I hope that I can represent San Francisco as honorably as I’ve tried to represent my own hometown. As my deadline approaches, I rely on the tools I’ve just shared more and more. I hope they serve you as much as they’ve been grounding me. Thank you.

Margaret Wilkerson Sexton studied creative writing at Dartmouth College and law at UC Berkeley. Her most recent novel, The Revisioners, won a 2020 Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize and an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work and was a national bestseller as well as a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her debut novel, A Kind of Freedom, was long-listed for the National Book Award. She lives in Oakland with her family.

Craft Talk Poetry Fiction Fiction Nonfiction Nonfiction Nonfiction

POETRY

Everything Is a Sign Today

by Amanda Moore

Feather in the grass, stippled and striped:

hawk, I think. And then a man

blocking the sidewalk, child on his back,

both of them pointing binoculars toward the treetop

where I know a great horned owl nests, though I’ve never seen it.

All these birds: creatures I might never have known

had I not spent my childhood filling her feeders, naming

each genus from our perch at her kitchen table.

A falcon swoops down beside me on the path

gripping some rodent in its talons, twisting the body to kill.

Like the time a heron a few feet from our picnic blanket

plucked a whole mouse from its burrow and swept away. She had been

delighted, said we, too, should grab something

of our own that day. Turning toward home,

I bend to collect a wrinkled postcard at the curb,

an advertisement for the Monet exhibit. How I loved

those paintings when I was younger, all of them nearly the same:

haystack, haystack, haystack. The only difference

the season and time of day, which is to say

they like this grief these months later:

all the same but for the light.

From Requeening by Amanda Moore. Copyright © 2021 by Amanda Moore. Reprinted courtesy of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Man in the Mouth of the Whale

Not swallowed, says the lobsterman, but engulfed

taken for krill ~~~~

tongued ~~~~

tasted ~~~~

transported ~~~~

spewed far from the boat that brought him.

Carried away :: he was surprised.

He was surprised :: he had been looking for something else.

He had been diving for lobster :: he was given a new life.

Who (there are few) ((if any))

that has been in the benthic maw

could ever hope to live in the world

as they once did? Conversion

so inconvenient: incontrovertible

proof but not in hand.

[we know these stories and their doubters]

How to photograph

a face inside a burning bush, an angel

as she gathers her skirt in one hand

& points toward the girl with the other?

You can hardly believe it

but feel the pressure squeezing

toward the baleen plates as they close

before you. You

are the man in the mouth of the whale

reaching down the gullet

to touch the place Jonah sat, where Gepetto

waited for his son. There is room for you there.

There is kindling for your fire.

It doesn’t matter

what you believe.

.

Yesterday diving for lobster.

Today a new way to be held.

Touched In Some Way and At Last

Enough of the sea! Let’s talk about

my new pair of shoes

that look better than they feel—I’ll blister

after a mile but will smile

the whole time. How wonderful

to have a place to go and time to be there.

We may choose to be late, we may choose

the elevator or the stairs. We’ll wear our hair

fresh-shorn and styled, falling smartly

at our chins. If you haven’t seen

the Twombly in a while, we must. Saying so

isn’t careless anymore. So won’t you

come along in a new dress? Comfort is over-

rated but not beauty. If we have forgotten

conversation, we’ll look

to the walls for words. See

how his line approximates letters,

how time passed approximates life. It will be good

to be once more in architecture. I’ll wait for you

in the lobby—how I love a lobby—where I can be

jostled, nudged, elbowed, shoved, and bumped.

Dawn Song

Ship in the distance, a floating house

of light. Like Gatsby’s at the end,

windows ablaze but each empty—

no human form to break the beams’ fall

onto a dimpled plane of sea.

Closer, daredevil surfers:

a bunch of tossed jacks, their bodies

cartwheeling over crests

and swallowed by foam.

Closer still, dogs off leash

kicking up sand,

barking their greetings to mist.

We are all untethered.

What might this morning be

from a meadow or a rooftop,

a mountain, or some distant city?

What curtain elsewhere

might pull back to newly frame

this same sky?

I long to know it all, each

horizon. Yet something

in my heart cries here, stay.

Amanda Moore’s debut collection of poetry, Requeening, was selected for the 2020 National Poetry Series by Ocean Vuong and published by HarperCollins/Ecco in October 2021. Poetry Co-editor at Women’s Voices for Change and a reader at VIDA Review and Bull City Press, Amanda is a high school English teacher and lives by the beach in the Outer Sunset neighborhood of San Francisco. More at http://amandapmoore.com.

Amanda Moore’s debut collection of poetry, Requeening, was selected for the 2020 National Poetry Series by Ocean Vuong and published by HarperCollins/Ecco in October 2021. Poetry Co-editor at Women’s Voices for Change and a reader at VIDA Review and Bull City Press, Amanda is a high school English teacher and lives by the beach in the Outer Sunset neighborhood of San Francisco. More at http://amandapmoore.com.

Craft Talk Poetry Fiction Fiction Nonfiction Nonfiction Nonfiction

FICTION

Use a Metronome

by Gregory Spatz

Only as he begins walking away from his car and sees his shadow on the ground ahead of him does he realize he has forgotten his hat. He touches a finger to his forehead to be certain and continues on his way in patches of fall brilliance, light scattered through hanging yellow leaves, or none, or few—late again for his office hours, always late, the third time this week alone.

How has he forgotten it, though? Where? It is, in a very real sense, a matter of life and death. A concession to inevitable, always-awaiting death. Every day, the skin doctor told him years ago—his first keratosis. He’d taken one of Edgar’s hands in his and held onto it, too long, to the point Edgar’s eyes began watering as they always did whenever he was faced with overt sincerity or any strong emotion that required him to express a reciprocal feeling. Every day, the doctor repeated, emphasizing his words with a tug on Edgar’s hand, another squeeze, I operate on someone like you. I mean exactly like you, not sort of. Not a day goes by, in fact, that I don’t operate. Melanomas, carcinomas, basal cell, squamous cell . . . But you don’t want me to operate on you! I don’t want to operate on you! So what can you do? Wear a hat! Sun block, sure. Why not? But the main thing is the hat. The head. Keep the head covered. Here he finally released Edgar to press the palm of his hand on Edgar’s forehead, a form of benediction mixed with diagnosis. He held it there awaiting a reply, a nod, which was difficult, given the hand. Capiche?

So he has. Hats every day. Berets and Greek fisherman caps and ball caps and for a while, until he lost it, a Harris Tweed newsboy hat right from the Isle of Harris, his grandmother’s homeland. But not today. Today the sun is hot on his skin and radiant through his scars, each old wound another reminder of death held at bay, one scalpel swipe at a time, one frigid blast from the liquid nitrogen canister at a time, and the air is cool on the newest blisters and incisions in their antibiotic dressing.

The hat, he pictures it now, is probably on the kitchen counter where he left it. Must be. Not far from a pile of orange rinds and not close enough to the puddle of spilled water and coffee grounds from his midday pick-me-up (coffee, bourbon, Bailey’s) to be any concern, exactly an arm’s length from the wall phone and the mason jar of mostly dead pens he keeps there for jotting down a name or number: the old stingy-brim black felt fedora. The jay feather in its band given to him by the woman whose voice through the phoneline had jangled nerves deeper than the reflexively receptive cochlear, had registered in his chest and solar plexus, his heart—had finally rattled him sufficiently so that, of course, as soon as he’d hung up he’d gone striding out of there, across the living room for his briefcase and out the door. The bare nob of his head too full of pictures and feelings even to register its own nakedness, until later—twenty-five minutes later, exactly—seeing his hatless shadow humping along the ground on his way across campus, when he felt for it and remembered, and then remembered why he’d forgotten.

But that wasn’t all of it. He’s spoken to her weekly or biweekly, sometimes more, sometimes less, since she was last here. And much as it still winds him up every time—the sound of her voice delivering him, like some spider cascading through space on a magical thread, back through the days to their last summers together—he’s almost used to it. He has multiple contexts for that voice now. Not just their summers in practice rooms together going over teaching strategies and notes, theories about how kids learn, and then driving out to one of a handful of local lakes and ponds in his old Saab or her Miata for the sunset, to see the pollen and haze-festooned light as the sun lowered and turned gold, red, cooler air blown at them from the center of the lake causing them to shift closer together and to feel everywhere their skin touched the magnification of their pleasure. And not just the physical images of her that always accompany such memories—black hair, blue eyes, the smart, tapping tips of her fingers against her violin’s fingerboard, and the sound she’d make just before playing, tossing the hair back, clearing her throat as if she were about to speak, and that old, portable Wittner Taktell metronome, edges scarred and worn from decades of travel, perched on the desk beside them, tick-tocking away, mechanically marking time until one or the other of them started in, turned its clacking to sound. Aside from all this he has as well the contexts of his empty days without her since—days and nights thinking of her, or on the phone together leaning at his kitchen counter, on the worn gold velour of his couch in the living room, or at the railing on the back deck overlooking the valley. Because she is the one, the only one for him, he hears in her voice not just their final summers together teaching music camp but an overlay of all the days since, always waiting for the news he knows, rationally, by now is not coming: I can’t stand another day apart. I’m moving out there to be with you once and for all. The hell with being married . . .

So really, it wasn’t just her call—her voice and her always-welcome but disruptive presence any given day of the week. It wasn’t just the effects of his pick-me-up either, somewhat stronger than usual, the bourbon splashing a few gargles past normal, the Bailey’s going a little faster into the mug. It was also the call just before hers and before the drink: the woman from the skin doctor’s office informing him that the results from the most recent biopsy were not so great, not conclusive exactly, not dire, but given the type of cells—new ones he hasn’t heard of—they need to go a little deeper, make sure the margins are clear, biopsy a few bone fragments to be sure. “Doc Corder says he’s been over it with you? Scraping the bone?” Scraping the bone? He doubted very much that he’d been over it or that it would matter all that much if he had.

Given that, given death and Dara and a stronger than normal afternoon pick-me-up followed with a splash of straight bourbon, it was no wonder he’d forgotten. Who wouldn’t forget? Who wouldn’t like to forget now and then (or more often than that, preferably) and as completely as possible? The problem was, in his case anyway, he always eventually remembered. And then once you’d remembered, as the philosophers liked to argue, you’d never really forgotten. So for him anyway, the act of forgetting was also always only the act of remembering and a reminder of the other age-old question: what was the point in any of it?

The point, he thinks. The point, tapping a rhythm against the change in his pocket with one hand and seizing the glass door in the other, pulling past his own reflection and reflections of the sky in the amber glass and stepping into the cavernous cool and dark of the music annex, so calming and familiar—the point . . . But he can’t bring the thought any further or find his way past it to any worthy tributary or secondary speculation, only the one word tick-tocking in his head with the sound of his footfalls on concrete, on stone, down the stairs, point point point, past the band room blaring with the noise of horns and timpani, the practice rooms where a joyless run of flute scales and trills snakes its way after him, through his ears as if it means to strangle all thought and hearing, past the same old yellowing cartoons on the doors of his colleagues, same old nameplates, same old posters advertising long gone concerts, same old everything (so is it any wonder he can hardly apprehend the passage of time?)—when, to his surprise, he finds himself standing outside the door of her office, not his own . . . what used to be Dara’s office, anyway, though now it belongs to a young German ethnomusicologist on loan for the year, one of a rotating cast of visiting professors and professionals who’ve occupied the space since Dara quit her position and moved back east . . . how many years ago? Was it really almost ten years ago now? A full decade? And those summers she returned to teach with him were . . . what? Again, he can’t track the thought to its end.

The ethnomusicologist is eyeing him in a friendly but suspicious manner through the dusty square lenses of his glasses. But he’s always a little friendly and suspicious of them. The Americans. It might not mean anything in particular. “Yes?” says the ethnomusicologist. He removes the glasses and wipes them on the tails of his shirt and sits forward suddenly with a creaking thud from his old, padded chair. That chair. Her chair. The one she’d been sitting in the day he first came up behind her and pressed with his palms on either side of her spine, the full length of his fingers kneading into her muscles, tentatively at first and then less so, his thumbs digging at the knots in her scapula with the low moan of her voice . . . Yes, oh, yes, yes. “Professor Carr. Can I help? You would maybe like to continue this discussion of African polyphony and polyrhythms from the other day? But I am a little busy just now so . . .”

“No, no! That’s all right.” He touches the top of his head. “Thought I’d left my . . .” he struggles for the word “. . . my hat. Here. Sorry. I see now I didn’t. Never mind. Did I? Anyway, if you see it, could you . . . ?”

“Oh, yes, if I see it. I will send it packing.”

“And the polyphony. To be sure. Another time . . .”

Here Edgar does a little fake bow and hand wave and begins his backward shuffle out, turns and goes down the hall to his own office where again he stops, a hand on the door, the image of her so clear in his mind he’s certain that to step through that door will be to erase it, kill her, or estrange himself from her for good. “Sorry,” he says, to the kid slumped on the floor outside his office, score open in his lap, earbuds wired to a device in an interior jacket pocket. Some kind of existential chasm looms between this moment and the next—between him right now and his scheduled meeting with this kid. What’s his name? If he could just see a little better, make out some of the notes on that score, maybe he’d figure it all out, prepare himself. The kid yanks out one of the earbuds and blinks questioningly at Edgar who again puts a hand on his own head and says, “Sorry. I’ve forgotten something. Back in a sec.” And out he goes through the downstairs emergency exit, into the last heat of summer, still chasing away that image of her approaching and receding in his mind’s eye at every corner, all the way around the building and back toward his car. “Hello! Beautiful day! Beautiful, beautiful,” he says to the group of students—members of the string quartet he’s set to meet with later, in an hour or so?—whose path crosses his as he goes, touching a hand again to the gooey, scabbed crown of his head. “Back in a flash.” They laugh and lean together and say whatever it is kids say about him these days. Now in full flagrance of the sun he makes his way through speckled patches of shadow and light, clouds of gnats and a late buzzing of locusts, the snap and hiss of a sprinkler coming on somewhere close enough that he detects a coolness of mist blown his way and gone again, to his car where he flings open the door and, finally, alone with the heat and surrounded in the old smells of his every trip and every last-minute consumed sandwich or candy bar or pre-packaged meal gobbled on his way to classes, concerts, rehearsals, baked into the upholstery along with the chemicals he’s used to erase those smells and the years of his soap and detergent and sweat and flatulence and whatever else his singular body has emitted in its daily struggles against cancer and work and cancer, always in a hurry—late, late, never on time—and trying to forget, both hands on the wheel and no destination in mind, he tips back against the headrest, eyes screwed shut as hard as he can, still trying to stop it, trying . . .

But it won’t be put off another moment.

He weeps. For everything. But mainly for her. He’s consumed by what’s nourished him these many years: the days of longing and anticipation. All that lost time. He tightens his facial muscles against the torrents of grief and hears the foolish hitch in his breathing, the sobbing, and still can’t stop, can’t gain any sort of control. He presses the heels of his palms into his eye sockets until he sees stars; until, opening them again pieces of his vision are temporarily blotted out, turned to static. “There,” he says. “There.”

So he’ll return her call tonight. He knows this about himself. Because she asked. She wants to know more.

He’ll talk and talk and tell her the latest with the skin docs, all the while waiting for the sign, the lull in conversation, the opening left so he can say something clearer, make his desire plainer. A visit! A meeting of the minds and the souls somewhere, anywhere! But he’s tried that already, recently even, and it hasn’t worked. No, Edgar, please, no, you know I can’t anymore and if you keep asking . . . Fine. So he won’t do that. He’ll wait and then he’ll switch off his lights thinking, Tomorrow. Maybe tomorrow. But what if there is no tomorrow? And with this, the pitch of this most histrionic and self-pitying thought—because of course one day there will be no more tomorrow, and of course there isn’t anything melodramatic or earthshaking or revelatory or even really that sad about it—while glimpsing his own reddened face and eyes in the rearview mirror, the hint of mirth back there in the eyes, the little self-mockery tinged with self-satisfaction for having allowed himself to finally break this once, to let go almost publicly, he sees it: there in the back seat of the car beside the pile of books he’d carried with him from the shelf beside the door and which he also thought he’d forgotten. Of course. His hat. The stingy-brim with the jay feather. Not forgotten after all. He scrubs with a knuckle at the corners of his eyes, growling at his own drunken idiocy, and blasts once into the yellow hankie she gave him. “Jesus H.,” he says aloud. Extracts himself again with the sound of his door’s electronic chime, unfolds into the light, slams shut his door, bends into the back seat for his hat and that forgotten pile of books, and with it perched on his head at a jaunty angle, roundhouse kicks the rear door shut. He heads back across campus to his office hours and his students awaiting him with the patience of angels, the patience of . . . something anyway—ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang—or maybe only the patience of young people needing to know how he’ll grade them on their latest efforts at becoming better musicians. He’ll tell them everything he can about love and loss and ruin, everything he knows—Can’t have one without the other! Can’t love without losing. Can’t lose if you don’t care. And music! Music without love is like a pair of wings and no bird! He’ll watch their faces for any indication that they understand what he means. Or maybe it’s risking too much, that kind of approach. Work harder, he’ll tell them. Use a metronome. Play like you give a goddam. You’ll be all right. And maybe they will be. Maybe that’s enough.

Gregory Spatz’s most recent book publications are What Could Be Saved (linked short stories and novellas), Half as Happy (short stories), and the novel Inukshuk. His short stories have appeared in or are forthcoming in The New Yorker, The New England Review, Kenyon Review, Epoch, Post Road Magazine, Santa Monica Review, and elsewhere. Recipient of a Washington State Book Award and an NEA Fellowship, he teaches in and directs the MFA program for creative writing at Eastern Washington University. http://www.gregoryspatz.com/

Gregory Spatz’s most recent book publications are What Could Be Saved (linked short stories and novellas), Half as Happy (short stories), and the novel Inukshuk. His short stories have appeared in or are forthcoming in The New Yorker, The New England Review, Kenyon Review, Epoch, Post Road Magazine, Santa Monica Review, and elsewhere. Recipient of a Washington State Book Award and an NEA Fellowship, he teaches in and directs the MFA program for creative writing at Eastern Washington University. http://www.gregoryspatz.com/

Craft Talk Poetry Fiction Fiction Nonfiction Nonfiction Nonfiction

FICTION

Gaps

by Matt Greene

We played a board game with mechs and peasants crossing rivers. They said they’d teach me and they told me what to do until it was too late for themselves.

I hadn’t been invited to their wedding. This hadn’t bothered me but now it bothered me that it didn’t.

They wanted waffles because every Sunday they ordered waffles, and I couldn’t eat waffles, but didn’t want to interfere with their ritual, so a man rang the doorbell and they ate waffles. It had been a long time since we last spoke and now we had gaps in each others’ lives.

I won the game. Aidan took me upstairs to see where the baby was sleeping. He didn’t ask if I wanted to hold the baby and I was glad because I was terrified of holding babies. The baby had been in the NICU. Now the baby’s doctors did not want the baby to leave the house and they did not want her mother to leave the house either. This was to last for a year and that year would end just as the sky greyed. Outside it was food trucks and Powell’s and etc. What the baby and I had in common is that we’d never ordered Uber Eats. I thought about how long after I died this baby would be living. But then again.

Aidan showed me the top floor. He’d converted it into a studio. There was a keyboard and drums and amps and a glimpse of Mt. St. Helens which neither he nor I nor the baby had been alive to see blow. I had forgotten he was a musician but now I remembered. What I thought of when I thought of him was not music.

Aidan said now I’d met the baby, but the baby had been asleep. I wasn’t sure it was even possible to meet a baby. We may have disagreed about the nature of consciousness, but, then again, maybe he was just being nice.

I got in my car. It was a six hour drive. I felt real bad and real good all at once.

I haven’t seen them since, but Aidan and I text each other our dreams. When I tell people this, they say All of them? And I say, Of Course. This is a lie.

Mostly the dreams slip away. Mostly I can feel only their residue, silhouettes and shapes of feeling. I jot down the half-remembered: labyrinthe subterranean malls with miles of gleaming concourse, robot claws hanging strips of meat in the rafters of ski lodge, a Seattle unrecognizably developed with subways and interlocking skyscrapers. Camping with Aidan and others, blurry pseudo-people who serve only to enact my guilt and shame, I am separated from the group. Always, I become separated from the group. And Aidan dreams this same dream too, only his groups are always moving up toward the mountaintops. I read his dreams over lunch, alone in a vast, fluorescent-lit community college shared office space, freckled gray carpet underfoot. In Aidan’s dreams, I am a trustworthy and worried accomplice. At a sheer vertical icewall to be climbed with picks, I refuse. Aidan hesitates, takes in the basalt crags and Douglas Firs that trace winding rivers, and keeps moving.

Matt Greene holds an MFA from Eastern Washington University and teaches English composition in Appalachia. “Gaps” is part of a linked series of prose pieces which have appeared in Arts & Letters, the Cincinnati Review, Hobart, Spillway, Wigleaf, and other journals. Other work appears in or is forthcoming from Alaska Quarterly Review, Conjunctions, and Santa Monica Review, among others.

NONFICTION

Words. Art.

by Lisa Alvarez

Most members of the Community of Writers know me from my summer self: co-director of the Writers Workshops, assistant to the Poetry Director, BFF to Brett, parent to one of the poetry elves and ever-present presence at the microphone announcing one event after another. But when summer’s over, like everyone else, I go home. Home for me is the foothills of Orange County, lots of oak trees and wildfires and a satisfying three decade long career of teaching at a community college in nearby Irvine. Like most everyone else at the conference, in between living and working, I write. A story there, a poem here, an essay over there. It’s a good life. This year that life expanded.

Most members of the Community of Writers know me from my summer self: co-director of the Writers Workshops, assistant to the Poetry Director, BFF to Brett, parent to one of the poetry elves and ever-present presence at the microphone announcing one event after another. But when summer’s over, like everyone else, I go home. Home for me is the foothills of Orange County, lots of oak trees and wildfires and a satisfying three decade long career of teaching at a community college in nearby Irvine. Like most everyone else at the conference, in between living and working, I write. A story there, a poem here, an essay over there. It’s a good life. This year that life expanded.

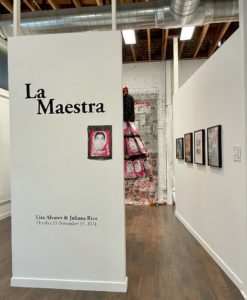

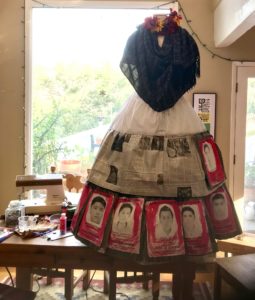

“Have you always used so many words in your art?” asked Alexa Lyon, the young college student intern assigned to interview me. The question came toward the end of an hour-long videotaped interview which began outside under the oaks and then, when the rain came, moved quickly inside my home. It was late September, a few weeks before the La Maestra exhibit was to open at Santa Ana’s Crear Studio in mid-October. The gallery director, Sarah Rafael García, and Lyon were conducting a “studio visit” to review my contributions to the show. The “studio” was my home and my “art” with “words” included a large hooped skirt made from newspapers and flyers and a wall-size broadside of a poem. The skirt commemorates the 43 students who were disappeared in Ayotzinapa, Mexico in 2014. For years I wore the garment to local Día de los Muertos celebrations and protests, a walking altar, a living reminder of that tragedy, a conspiracy that involved the military, the government and drug cartels. In between appearances, the skirt was carefully stashed in our garden shed. The poem, “Reading Last Month’s Newspaper Today,” was written in response to the disappearance as well, the wall-size 5 x 12 feet broadside of stitched-together newspapers created expressly for the La Maestra exhibit. The exhibit showcased my two pieces along with photographs curated by Juliana Rico, drawn from her students who documented social movements and celebrations. Both Rico and I are teachers, professors at local community colleges – hence the name of the show, La Maestra, given to it by García, who is, as it happens, a former student of mine.

But back to that question about words and art. I hadn’t thought of myself as an artist, a visual artist, until García suggested that my skirt was exactly that. Sure, in my 20s, I had a short-lived flirtation with performance art in the 80s. Who didn’t? But since that time, I’d been a writer, albeit a writer with a penchant for guerrilla theatre who from time to time liked to create small and large spectacles, often in service of political causes. Was that art? Or was that just what I did?

But back to that question about words and art. I hadn’t thought of myself as an artist, a visual artist, until García suggested that my skirt was exactly that. Sure, in my 20s, I had a short-lived flirtation with performance art in the 80s. Who didn’t? But since that time, I’d been a writer, albeit a writer with a penchant for guerrilla theatre who from time to time liked to create small and large spectacles, often in service of political causes. Was that art? Or was that just what I did?

Then García gave me this wonderful opportunity to “show” – at age 60 – and to think of what I made as “art.” The intern’s question: “Have you always used so many words in your art?” received a quick reply: Of course. First and foremost, I am a writer. I use words. I love words. Words are power. Words are art. I want so much to use my words in service of story and art and liberation, whether on the page where I am most comfortable or, in the street as an impromptu performance or protest or as it may happen, once and I hope again, in a gallery. It is all, after all, one and the same.

Crear Studio is a project of LibroMobile Arts Cooperative, founded in 2016, a community based collaboration between a mobile bookstore and cultural center practices. It builds on anti-gentrification movement culture and cultivates diversity through literature and the arts by prioritizing Black, Indigenous and people of color and integrating free reading and writing programs, visual exhibits and year-round creative workshops in Santa Ana, California and surrounding areas. For more information: https://www.libromobile.com

Lisa Alvarez’s poetry and prose has been published in Air/Light, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, Huizache, [PANK], Santa Monica Review, TAB Journal and most recently in So It Goes, the literary journal of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library as well as anthologies including Sudden Fiction Latino: Short-Short Stories from the United States and Latin America(Norton). With Andrew Tonkovich, she co-edited Orange County: A Literary Field Guide (Heyday). She is the editor of Why to These Rocks: 50 Years of Poems from the Community of Writers (Heyday). Born in Los Angeles, she earned an MFA from UC Irvine and has taught for nearly 30 years as a professor of English at Irvine Valley College. She co-directs the Writers Workshops, and serves serves as Assistant Program Director at the Community of Writers.

Craft Talk Poetry Fiction Fiction Nonfiction Nonfiction Nonfiction

NONFICTION

Peaks and Valleys

by Gail Reitano

For me, the Community of Writers has always been a bellwether. Each of the six times I attended, as July approached, I wondered what it would be like, who I might meet, and of course every year was different. (If anyone has attended that many times, please get in touch!)

In 2002, at my fourth conference, several writers in my workshop group had high-paying jobs in tech. In the words of one, he’d come to the Community “to bang out a novel.” That was the year I had my one and only taste of the meanness that can sometimes happen in group critiquing sessions. My mistake was one common to many beginning writers, the use of somewhat inflated language. That year, the offending word was nascent.

“Naaaascent…” drawled the first.

“Nascent?” queried the next.

“I don’t like the word nascent,” intoned a third.

After that, they fell like dominos, and soon all I heard was my beating heart. A notable exception to this avalanche was a man who would go on to write one of the most successful shows in television history. Given what had come before, his lone voice in support was not only generous, but nothing less than heroic, and his “I like Gail’s writing,” a life raft. After the workshop, with my hands shaking, I bummed a cigarette from Mark Childress. And as we stood smoking and looking out through the pines and firs of the valley, he talked me down off the ledge with this advice: “Take what you need and jettison the rest.”

That was the same year that the writer, Richard Ford, while running our morning workshop, asked us each how many times we’d attended. Hearing of my persistence, he turned, and with palpable excitement said, “I admire that. It’s what it takes to get one’s writing to where it needs to be.” I had been feeling embarrassed, now I experienced a small jolt of pride.

In 2019, sixteen years had passed since my last time in the valley. There was a brand-new crop of authors leading the workshops, and the participants seemed to have gotten a whole lot younger. Of some consolation was the fact that I now had a body of work, I’d published a handful of stories and essays, and my novel Italian Love Cake was out being read by publishers. I was also working on a new novel, and another—my White Whale—was still in its box, in reasonable shape, waiting. But why wasn’t I further along in my writing career?

Dutifully, I took a seat at the always well-attended agent panel, and I soon realized I’d queried three of the five on the dais with a previous novel and had been rejected by all three. But I was suddenly feeling bold, and a different me raised her hand. “Excuse me. If three of you have already rejected me, do you think I could query you again?” Nervous laughter, followed by, “Sure, though not with the same project.” More laughter. It felt good to admit publicly how hard I’d been trying, how difficult the writing life was, and how, despite that, I was still in the game.

A month after the 2019 conference, Italian Love Cake was accepted for publication by Bordighera Press. It’s hard to put into words what this felt like after my many attempts with several different books. With that acceptance, I realized two dreams. I would publish a longer work, and I could finally bring forward an Italian American history largely unrepresented in the mainstream literary marketplace. My subject was a pre-WWII generation of Italian immigrant women, and as I wrote Italian Love Cake I channeled my own struggles, determined to make a story that takes place in the 1930s, contemporary. The common thread was women’s ongoing fight to be heard, respected, treated equally—similar in fact to the Italian American’s fight to be taken seriously, respected, and to overcome negative stereotypes.

For a long time, I’d rejected the term Italian American; I resisted reading or writing “Italian” stories of any kind. But I never stopped puzzling over how to drag a thread through from Italy to America, to lay claim to that older country where we’d left behind so much of ourselves in the rush to assimilate. It was the discovery of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels that gave me the courage to try. Reading her, it was as though I’d finally been given permission to put Italians front and center in my own writing. I decided on a historical narrative as the best way for me to uncover our buried stories.

Shortly after Italian Love Cake came out this year, a French publisher contacted me wanting to do a translation. Fittingly, the French edition will have an Italian title, “Liberata,” meaning “Liberated” or “The Liberated Woman.”

Writing is a form of liberation, and if my years of workshopping have taught me anything, it’s to approach the entire enterprise with humility and a feeling of freedom. The Community has always functioned as a safe environment, and it’s impossible to imagine where I’d be without the rigor, the kindness, even the occasional sharp, succinct word, all of it propelling me toward making better work.

We derive strength, ideas, and stimulation from each other. Community of Writers was my first community, and I’m grateful to have found it.

Gail Reitano grew up in the southern New Jersey Pine Barrens. She graduated from Rutgers University and lived in London for twelve years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area. Her fiction, memoir and personal essays have appeared in Glimmer Train, Catamaran Literary Reader, and Ovunque Siamo, among others, as well as featured on public radio in the Bay Area. Italian Love Cake (Bordighera Press) is her first novel; the French translation, Liberata, is coming in May 2022 (Éditions Anne Carrière).

Gail Reitano grew up in the southern New Jersey Pine Barrens. She graduated from Rutgers University and lived in London for twelve years before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area. Her fiction, memoir and personal essays have appeared in Glimmer Train, Catamaran Literary Reader, and Ovunque Siamo, among others, as well as featured on public radio in the Bay Area. Italian Love Cake (Bordighera Press) is her first novel; the French translation, Liberata, is coming in May 2022 (Éditions Anne Carrière).

Craft Talk Poetry Fiction Fiction Nonfiction Nonfiction Nonfiction

NONFICTION

From Your Farflung Correspondent:

by Tom Lutz

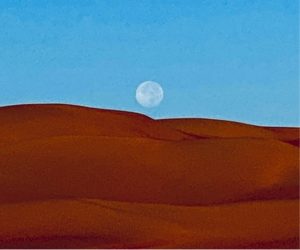

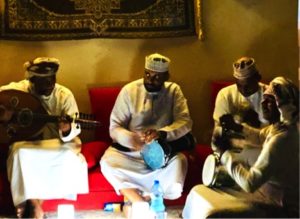

Walking in the desert, in the Wahiba Sands, a five-thousand square mile expanse of rolling dunes, is a bit like walking on snow that has iced up on top. The wind lifts the softer sand off, and what doesn’t get blown away gets blown into itself, forming a light crust. If you walk carefully, and watch where you are stepping, you can stay on top of it, but most of the time you crack through, an inch or two or three, more as you scramble up the steeper slopes, and you spray a bit of sand in front of each foot as you go.

Walking in the desert, in the Wahiba Sands, a five-thousand square mile expanse of rolling dunes, is a bit like walking on snow that has iced up on top. The wind lifts the softer sand off, and what doesn’t get blown away gets blown into itself, forming a light crust. If you walk carefully, and watch where you are stepping, you can stay on top of it, but most of the time you crack through, an inch or two or three, more as you scramble up the steeper slopes, and you spray a bit of sand in front of each foot as you go.

The Wahiba Sands were named for the Bani Wahiba, a tribe of Bedouins who have lived in the desert for as long as anyone remembers, along with the Amr, Janaba, Hishm, and others. The sand moves with the wind, and forms into tiny ridges, as high as a coin, reforming each day. Footprints begin with the clear pattern of the sole of a shoe, like a plaster cast made by a forensic team. Within an hour the print has gone out of focus, in a few hours it is a slight depression, and by the next morning it is gone. For centuries, the only footprints were Bedouin, but in recent decades, encouraged by the modernizing Sultan Qaboos, tourism has arrived, and desert camps have sprung up along the edges of the sands. Now the temporary footprints are made by Europeans, Asians, Arabs, and others, and each day there are new tracks of 4X4 SUVs and recreational buggies laid down and erased. Also erased have been the Wahiba, as the government has rechristened the area the Sharquiyah Sands.

The Wahiba Sands were named for the Bani Wahiba, a tribe of Bedouins who have lived in the desert for as long as anyone remembers, along with the Amr, Janaba, Hishm, and others. The sand moves with the wind, and forms into tiny ridges, as high as a coin, reforming each day. Footprints begin with the clear pattern of the sole of a shoe, like a plaster cast made by a forensic team. Within an hour the print has gone out of focus, in a few hours it is a slight depression, and by the next morning it is gone. For centuries, the only footprints were Bedouin, but in recent decades, encouraged by the modernizing Sultan Qaboos, tourism has arrived, and desert camps have sprung up along the edges of the sands. Now the temporary footprints are made by Europeans, Asians, Arabs, and others, and each day there are new tracks of 4X4 SUVs and recreational buggies laid down and erased. Also erased have been the Wahiba, as the government has rechristened the area the Sharquiyah Sands.

Like walking in snow, walking on the dunes is slow, and scrambling up the tall dunes, a hundred feet high, even slower, your foot slipping down the hill a bit with each step. A few kilometers in, I came to one of the desert camps, a compound with a hundred tents and villas, most with one bedroom, a few larger for families. It had been closed during the pandemic, and it was usually closed in the summer months anyway, when temperatures of 110 degrees and monsoon winds make it inhospitable. The front gate had a sign saying nobody was allowed to enter without a reservation, and a phone number to call. I saw a man inside and approached him, apologizing for not having a reservation, saying I just wanted a look inside. He was from Bangladesh, but had been working at the camp for ten years. Many of the workers at this camp and the others were from Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. He was now a manager, and he agreed to show me around. There were only five guests that day, and they were out, so we would disturb no one.

Like walking in snow, walking on the dunes is slow, and scrambling up the tall dunes, a hundred feet high, even slower, your foot slipping down the hill a bit with each step. A few kilometers in, I came to one of the desert camps, a compound with a hundred tents and villas, most with one bedroom, a few larger for families. It had been closed during the pandemic, and it was usually closed in the summer months anyway, when temperatures of 110 degrees and monsoon winds make it inhospitable. The front gate had a sign saying nobody was allowed to enter without a reservation, and a phone number to call. I saw a man inside and approached him, apologizing for not having a reservation, saying I just wanted a look inside. He was from Bangladesh, but had been working at the camp for ten years. Many of the workers at this camp and the others were from Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. He was now a manager, and he agreed to show me around. There were only five guests that day, and they were out, so we would disturb no one.

We talked about the camp, and his recent visit home to Dhaka, which he didn’t love, because it was so crowded, although he loved the rest of the country, the beaches, the mangrove forests, the north. He said if you love nature, you love Bangladesh. Except Dhaka. I said I loved Dhaka, too, and he shrugged—he was too good natured and even keeled to find other people’s opinions a problem. He gave the slightest of shrugs.

We talked about the camp, and his recent visit home to Dhaka, which he didn’t love, because it was so crowded, although he loved the rest of the country, the beaches, the mangrove forests, the north. He said if you love nature, you love Bangladesh. Except Dhaka. I said I loved Dhaka, too, and he shrugged—he was too good natured and even keeled to find other people’s opinions a problem. He gave the slightest of shrugs.

I asked how Oman was as a country for immigrants. He took a moment, a long moment.

I asked how Oman was as a country for immigrants. He took a moment, a long moment.

“This is a fortunate destination for us,” he said, quietly, looking me in the eye with a tinge of sadness in his own, and no smile. The sentence held complex significance, and it was so heartfelt and thoughtful that I had to respect his carefulness by not pushing, not

asking a follow-up. I took him to mean that it was fortunate compared to his prospects at home in teeming Dhaka, but that it was not without its troubles. The tone was melancholy. I had been on the Arabian Peninsula for some weeks, and had been here before, and had seen the sedimented service class of immigrants in the Emirates, in Qatar, in Saudi Arabia. They were, even to the untutored eyes of a tourist, treated as second-class non-citizens. “It is important, I think” he continued, in the same way, “It is necessary for us to love where we find ourselves.” He said this without any enthusiasm or pride, just acceptance. Again, there was wisdom, gratitude, sadness, appreciation, and even grief wrapped up in the simple statement. It struck me as sagacious, hard-won, but also just who he was—he was a young man with an old soul, willing and determined to love what the world allowed.

asking a follow-up. I took him to mean that it was fortunate compared to his prospects at home in teeming Dhaka, but that it was not without its troubles. The tone was melancholy. I had been on the Arabian Peninsula for some weeks, and had been here before, and had seen the sedimented service class of immigrants in the Emirates, in Qatar, in Saudi Arabia. They were, even to the untutored eyes of a tourist, treated as second-class non-citizens. “It is important, I think” he continued, in the same way, “It is necessary for us to love where we find ourselves.” He said this without any enthusiasm or pride, just acceptance. Again, there was wisdom, gratitude, sadness, appreciation, and even grief wrapped up in the simple statement. It struck me as sagacious, hard-won, but also just who he was—he was a young man with an old soul, willing and determined to love what the world allowed.

I left him and continued my trek, wondering at the constant beauty of the dunes, the wind a consummate painter; at the trees, their lower branches trimmed in a perfectly straight line at the height of the taller camels’ teeth; at the absolute symmetry of a dung beetle’s tracks, two inches wide and unerring as a machine; at how stupidly easy it was for me to love where I was. I could do it without any wisdom at all.

I left him and continued my trek, wondering at the constant beauty of the dunes, the wind a consummate painter; at the trees, their lower branches trimmed in a perfectly straight line at the height of the taller camels’ teeth; at the absolute symmetry of a dung beetle’s tracks, two inches wide and unerring as a machine; at how stupidly easy it was for me to love where I was. I could do it without any wisdom at all.

I am on sabbatical this year, stacking privilege upon privilege, and I feel myself going in opposite directions. In many ways I am beginning the process of the Great Wind-down. I’ve left Los Angeles Review of Books in the capable hands of Boris Dralyuk and Irene Yoon, and the department I chair at UCR in those of Josh Emmons. I knew ages ago that I wouldn’t want LARB to suffer from founder’s syndrome, that it needed to live and grow without me at the helm, and so that fifty hours a week I have back now. I will come back in another nine months or so to UCR, where I will teach for one more year, maybe two, but that’s it, then I’m done with that part of my life, too. What happens, it turns out, when I don’t have all those chores to deal with is that I write. We’ve been on the road for almost four months now, and I’ve written a new noir novel that I like and a number of travel-based narrative essays for volume

I am on sabbatical this year, stacking privilege upon privilege, and I feel myself going in opposite directions. In many ways I am beginning the process of the Great Wind-down. I’ve left Los Angeles Review of Books in the capable hands of Boris Dralyuk and Irene Yoon, and the department I chair at UCR in those of Josh Emmons. I knew ages ago that I wouldn’t want LARB to suffer from founder’s syndrome, that it needed to live and grow without me at the helm, and so that fifty hours a week I have back now. I will come back in another nine months or so to UCR, where I will teach for one more year, maybe two, but that’s it, then I’m done with that part of my life, too. What happens, it turns out, when I don’t have all those chores to deal with is that I write. We’ve been on the road for almost four months now, and I’ve written a new noir novel that I like and a number of travel-based narrative essays for volume

four, ominously titled The End of the Road (the third volume, The Kindness of Strangers, is just out). I’ve worked on two other novels, one a campus novel and the other based on the Teapot Dome scandal. I doodled a bit on a book about 1925, too. Who knows if any of those three will become books. We’ll see. But who cares? I’m living a writer’s dream life, and it is, in fact, much as I pictured it. At the place I’m staying in the desert, a man passed me at breakfast as I was typing, and he said, “You work all the time, yes?” And I said, “No, it’s not really working. It’s writing.”

four, ominously titled The End of the Road (the third volume, The Kindness of Strangers, is just out). I’ve worked on two other novels, one a campus novel and the other based on the Teapot Dome scandal. I doodled a bit on a book about 1925, too. Who knows if any of those three will become books. We’ll see. But who cares? I’m living a writer’s dream life, and it is, in fact, much as I pictured it. At the place I’m staying in the desert, a man passed me at breakfast as I was typing, and he said, “You work all the time, yes?” And I said, “No, it’s not really working. It’s writing.”

Tom Lutz is the American Book Award-winning author of eleven books and the founding editor of Los Angeles Review of Books. His most recent books are Born Slippy (2020), a novel; Aimlessness (2021), a lyrical-philosophical essay on blundering about as method; and The Kindness of Strangers (2021), the third book in his travel trilogy. He is finishing up a collection of photographic portraits with micro-essays, and working on a new novel and a book about violence along the aridity line. https://lareviewofbooks.org/contributor/tom-lutz/

Tom Lutz is the American Book Award-winning author of eleven books and the founding editor of Los Angeles Review of Books. His most recent books are Born Slippy (2020), a novel; Aimlessness (2021), a lyrical-philosophical essay on blundering about as method; and The Kindness of Strangers (2021), the third book in his travel trilogy. He is finishing up a collection of photographic portraits with micro-essays, and working on a new novel and a book about violence along the aridity line. https://lareviewofbooks.org/contributor/tom-lutz/

Craft Talk Poetry Fiction Fiction Nonfiction Nonfiction Nonfiction

Editor’s Note

Andrew Tonkovich

Editor, OGQ

ABOUT THE OGQ

Omnium Gatherum Quarterly (OGQ) is an invitational online quarterly magazine of prose and poetry, founded in 2019 as part of the 50th Anniversary of the Community of Writers. OGQ seeks to feature works first written in, found during, or inspired by the week in the valley. Only work selected from our alums and teaching staff will appear here. Conceived and edited by Andrew Tonkovich. Submissions will not be considered.