EDITOR’S NOTE

By Andrew Tonkovich

Some of us will have seen our community at elevation this summer, with happy reunions, new friendships made, and group celebrations of publication or other personal and professional successes. Best of all, this representative group will have gathered for workshops, craft talks, meals, readings, and the much-welcomed affirmation that our writerly community exists in-person, for real, for two full weeks — under the stars, out on the deck with a view of the Granite Chief — in addition to being manifest year-round in robust online programming, short courses, podcasts, CW books and anthologies, scholarship programs, alumni news and more.

This issue of our invitation-only quarterly is a dispatch from all over featuring generous and wildly eclectic, smart, thoughtful, and funny contributions by staff and alums. Subjects include craft advice, Nancy Drew, relying on poetry in the pandemic, Chicago house music, Jacques Cousteau, Sparkle Stories, picking a title, Nobel prize awards, 1950’s Havana, mimes, abstract artist Agnes Martin, in addition to poetry and autobiography and so much excellent writing that you’d almost wish our community had in the past couple of years also produced its own terrific bespoke literary arts journal featuring amazing writing about writing, by writers, and for writers.

And, just like that, your wish is granted. Please read, enjoy, and share this issue. It’s a good one!

Andrew Tonkovich

Editor, OGQ

A CASE AGAINST KILLING YOUR DARLINGS

By R.O. Kwon

The phrase “kill your darlings” is a lifelong foe. I’ve never quite understood it, prevalent as the idea can be. I take the injunction to mean I should get rid of the best parts of what I’m working on: the lines I feel especially alive while rereading, the metaphors so bewitching it seems possible I, too, along with the language, might be transfigured.

To which I say: fuck, no. Absolutely not. Why would I cut, let alone kill, that which most delights me?

I refuse, so here’s what I believe: I want any novel I write to be full of darlings. If possible, all darlings. I don’t want any published novel of mine to include a single line that bores me, that hasn’t been shaped, pressed, and attentively loved into the most truthful, living version of itself. I might even argue that it’s not possible to care too much about language, about punctuation. I am close to believing, at least with my own work, that a single misplaced comma is enough to risk bringing down an entire book. One careless line is a death knell; a paragraph, utter ruin.

Not everyone believes this, of course, which is as it should be. The house of fiction is large; it holds infinite rooms, and if you’re a writer, part of your life’s work will be learning what holds true inside your own, uniquely splendid room. Which you’ll figure out by reading a lot and writing, but especially reading. It’s how I started better understanding what kind of writing I had to try to write: I realized I usually decide which book I’ll read next by glancing at a few lines from the middle of the text. If those lines sing to me, I’ll then flip to the beginning and read the book; if I can’t hear the lines’ singing, I’ll put down the book and try the next one in the pile.

So, I started applying that same test to my own writing. With both of my novels—including the one that published this year, Exhibit—each time I’d finished a draft, I would read it through, pull out the lines I loved, put them in a new document, then start again. I did that for the first god knows how many drafts; by the end, I’d write thirty novel drafts, fifty, I have no idea, and I don’t want to know.

Only when I had a more substantial draft did I start working with the words I had in place, trying to pull every phrase, line, and page up to the level at which the so-called darlings, like higher beings, already existed. I knew I might have finished Exhibit when I could open the book at random, read a few lines, and not feel compelled to revise it all over again.

R. O. Kwon’s Exhibit, a novel, is out with Riverhead. Kwon’s nationally bestselling first novel, The Incendiaries, has been translated into seven languages and was named a best book of the year by over forty publications. The Incendiaries was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Award. Kwon and Garth Greenwell co-edited the bestselling Kink, a New York Times Notable Book and recipient of the inaugural Joy Award. Kwon’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Guardian, and elsewhere. She has received fellowships and awards from MacDowell, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Yaddo. Born in Seoul, Kwon has lived most of her life in the United States.

R. O. Kwon’s Exhibit, a novel, is out with Riverhead. Kwon’s nationally bestselling first novel, The Incendiaries, has been translated into seven languages and was named a best book of the year by over forty publications. The Incendiaries was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Award. Kwon and Garth Greenwell co-edited the bestselling Kink, a New York Times Notable Book and recipient of the inaugural Joy Award. Kwon’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Guardian, and elsewhere. She has received fellowships and awards from MacDowell, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Yaddo. Born in Seoul, Kwon has lived most of her life in the United States.

THE PALACE OF FORTY PILLARS

by Armen Davoudian

Author’s note: Here is an excerpt from the title poem of my new collection, The Palace of Forty Pillars, which grew out of a draft I actually wrote in Olympic Valley for Robert Hass’s workshop.

Isfahan is half the world

Twenty pillars drip into the pool

their likenesses, where the likeness of a boy

wavers among the clouds, eyeing the boy

who’s waiting for another. All is dual:

two rows of roses frame the pool, in twos

the swans glide, each on another’s breast, then fuse

in a headless embrace. All is dissolved:

the boy outside the water is no more

a boy inside the water—his no more

the face defaced by its own lines on shattered

waves overlapping like a rose, the tattered

pillars strewn like petals. All is halved,

severed, like home and school, like love and being

loved—the boy no more than a way of seeing.

Armen Davoudian is the author of the poetry collection The Palace of Forty Pillars (Tin House) and the translator, from Persian, of Hopscotch by Fatemeh Shams (Ugly Duckling Presse). He grew up in Isfahan, Iran, and is a PhD candidate in English at Stanford University.

Armen Davoudian is the author of the poetry collection The Palace of Forty Pillars (Tin House) and the translator, from Persian, of Hopscotch by Fatemeh Shams (Ugly Duckling Presse). He grew up in Isfahan, Iran, and is a PhD candidate in English at Stanford University.

BREAKING THE STORY

by Cameron Walker

Maybe stories only found me again because I didn’t know what else to do. It was an afternoon in early December, and I had a new baby and two older boys, three and five, already buzzing with holiday energy. I was exhausted, pinned against the pillows by the nursing baby, by the two small bodies bouncing on the bed around us. The light coming through the bedroom windows was that cold, sideways winter light that felt like it could bruise.

The thump of the dryer. The shrieks of the boys. The anticipation of the baby’s cry. It was all too much noise, too much motion. “Hey,” I said. “Hey.” Maybe they stopped bouncing, maybe they didn’t. “I heard about some stories we could listen to. Should we give that a try?”

In my imagination, they settled instantly, which can’t be right. But what is true is that a few minutes into the story–this one about mysterious yellow cards that appear each day of Advent, the season leading up to Christmas–they were not bouncing anymore.

Stories have always had a way of settling me. When I had trouble sleeping as a kid, my dad would come and lie on the floor next to my bed—his back hurt—and tell me about the alligator who lived in his neighbor’s bathtub. When I was a little older, I’d wake and turn the light back on and flip through fairytales, and later, epic fantasies with wizards and elves.

Even though the only consistent thing I’d done in my adult life was writing, I never felt like a real storyteller. When my kids asked for a story, I was struggled to come up with what happened next, and then would reel the story so far out (Fire-breathing dragons! Exploding volcanoes! Mysterious underground tunnels leading to a world where pumpkins grew to be the size of houses!) I would forget how to find my way back.

But these stories we were listening to—they’re called Sparkle Stories, if you’re interested—were mostly about everyday life with a family. There were no volcanic eruptions or giant pumpkins. Still, everyone was fascinated. (Also, quiet.) So when I heard that the Sparkle Stories’ storyteller—a man named David Sewell McCann—was giving classes on storytelling, I signed up.

It was one of those calls that I was doing from the bedroom floor, early in the morning, and I can’t really remember what we talked about at first, but that the baby, now old enough to walk and talk, flung open the bedroom door and asked me a question. I glanced away from the phone to answer—wanting to help my son, wanting to get back to the conversation, and also feeling like my parenting skills were on display in the discomfort of trying to do both things at once.

When I looked back at the phone, David was smiling. “That’s the story,” he said.

He told me that storytelling was really following your attention and where it took you. When I looked at my son, he said, my whole energy shifted. That’s what happened when he told a story—he paid attention to the places where his energy wanted to go, and then he went there.

This idea felt like a life raft at a time when my attention felt particularly scattered. Kids were slamming in and out of rooms, waking up from naps, coming home from schools with fevers. Then later, of course, there were no schools to come home from. I took comfort in the idea that I could still write wherever my attention went, even when the whole world was splintering.

I wrote the splinters. When the kids were everywhere, I wrote them everywhere. I wrote the beach we walked on and the scrub jays we watched in the backyard and the theme weeks we created to pretend that we were at a magical summer camp and everything was going to be all right: medieval week, bird week, garden week. Even potato week, when I had really run out of ideas.

The other thing that stuck around from my conversation with David—I’m sure I wrote notes down, but like my attention, the notebook wandered elsewhere—was the idea that somewhere, near the end of the story, he tries to break it. Break it? I had this idea of someone throwing a plate against the wall and the sound that the plate would make as it shattered. But I had never actually thrown a plate. I didn’t know how to make something break when I’d spent so long trying to fix things.

He said that I’d know it when it happened.

I’ve been thinking about this idea, and this essay, and haven’t been sure still quite what it means, or how to break this one. I don’t like breaking things. It makes me feel wasteful, terrible, a little bit lost. And I was still thinking about the breaking this morning, when I was reading our local weekly and saw a story about how whales hear noise in the Santa Barbara Channel, how it’s cacophony out there, how they would have to shout their whale song to be heard.

Researchers compared the noise levels in the Channel in the 1950s, before cargo ships started to rumble through the channel, to how this stretch of water sounded in 2017. Maybe it’s no surprise that everything has gotten much, much louder. The Channel’s underwater contours make any noise reverberate, turn this passageway into a submarine concert hall with no emergency exit doors. The blue whales that spend summers foraging in and around the Channel, the researchers suggest, may have trouble hearing each other, along with being under constant stress from all the background sound.

What could feel more broken than not being able to hear each other? That’s why it can feel so hard to tell stories, I think. There is so much noise, it can be hard to pay attention to anything but the noise. It can be hard to do anything that feels like it might just be making more noise. I don’t want to be part of an endless orchestra of engines that is only growing louder, that is drowning out whatever it is I most want to hear.

But listen. Somewhere under all the sputter and churn there is still a creature with the largest heart in the world, singing. There is still a room, back in time, when three boys went quiet in the slanted winter sunlight to hear a story that felt as true as whale song. There is still a room where I imagine you and your own large heart, a blank page in front of you. You are about to make something that is so much more than noise, a sound that makes the world easier to bear, and the rest of will be able to sit still for a moment in our own rooms and pay attention.

Cameron Walker is a writer based in California. Her new essay collection, Points of Light: Curious Essays on Science, Nature, and Other Wonders Along the Pacific Coast, won the Tamaqua Award from Hidden River Press. She is the author of National Monuments of the U.S.A., a book for kids beautifully illustrated by Chris Turnham, and of How to Capture Carbon, a collection of short stories that will be published by What Books Press in fall 2024.

Cameron Walker is a writer based in California. Her new essay collection, Points of Light: Curious Essays on Science, Nature, and Other Wonders Along the Pacific Coast, won the Tamaqua Award from Hidden River Press. She is the author of National Monuments of the U.S.A., a book for kids beautifully illustrated by Chris Turnham, and of How to Capture Carbon, a collection of short stories that will be published by What Books Press in fall 2024.

by Sara Ellen Fowler

Some psychics need to scry, some need to scribble wide, ugly pen marks into bulky sketchbooks in order to open their channel, in order to listen. In art school, as an undergraduate, I found my ear through my hands, ravenous as a raccoon, busy to unmake, unspool, and ruin—all manner of objects, garments, furniture I’d scavenged, second-hand. I was magnetized to dross and wielded permission to pull the pieces further apart. To give them air, give them light, the instinct to rend and rend until some essential element yielded—a new insight would race across my vision.

I made performances, videos, and sculptures: talismans of an inner world where language, too, was at the ready. There was always a notebook open in my studio. Spiral-bound, college ruled Bazic notebooks, product of Indonesia, with a pliant paper weight and seductive transparency that I found at Brown and Welin, a compounding pharmacy opened in 1946 in Pasadena, CA. What language sifted to the surface of my consciousness—in the trance of hours, days and weeks, I sat separating the orange and yellow warp and weft of a woven coverlet—I created a transcription. From this origin, temperature and texture and all the formal trappings of sculpture gained grammar. A confusion of sensory information and verbal impression earned a third wit; I touched an electric searching that I would come to understand as poetic mind.

There is a synesthetic contract of close attention and deep feeling alive in Two Signatures (University of Utah Press, 2024), my first book. It is a document that traces dilations of desire and power in my life in the decade after art school as I learned to make a studio of language. I claimed poetry as an art practice, put my physical materials in storage, and set about reinventing how I recorded my attention and curiosity. By hand, in my notebooks, I began charting psycho-spiritual revelations homed in the body’s humble interface with the everyday.

There is a synesthetic contract of close attention and deep feeling alive in Two Signatures (University of Utah Press, 2024), my first book. It is a document that traces dilations of desire and power in my life in the decade after art school as I learned to make a studio of language. I claimed poetry as an art practice, put my physical materials in storage, and set about reinventing how I recorded my attention and curiosity. By hand, in my notebooks, I began charting psycho-spiritual revelations homed in the body’s humble interface with the everyday.

In addition to tableau with lovers and self discovery, the animation of desire and power is found in my experiments in the field of ekphrasis, too. Utilizing details from an artist’s biography in addition to the lively physical stance of their specific practice, I home a searching persona in the particular psychological conditions of art making. Eva Hesse and Agnes Martin are my muses, in this method, in the book. The prose poem “Window” describes: “My canvases fain shudder in the temperature like a horse’s rippling will. I believe in the horizon only. O, let me be hulled in it. A mixed pulse, a wash of, I take the pills: silent dress circle of what care I need to keep painting here.” The poem imagines a galvanized Taos studio in the footprints of pioneering abstract painter Agnes Martin, who left New York and worked for decades in the desert, for its stabilizing sensory balm, while living with a schizophrenia diagnosis. The values that foregrounded Martin’s decision to find peace in the rigid and generous structure of her studio inspire me, as a bipolar person, as I build an expressive practice with candor and insistence. This poem sings an intimate stewardship.

The valences of my book’s title reach across multiple themes homed inside:

One of the foundational questions I was working as I began writing, revising, and sequencing this book: What are signatures of trust and how might they be held, faceted in language? In the trajectory of the book, a reader will find a speaker coming to terms with their own agency. Signatures of mood, psycho-spiritual conditions, and mental illness are expressed in the first-person and also as subject through honoring the legacies of poets Marni Ludwig and Sylvia Plath, who both alchemized psychic pain and succumbed to its torment. “There is a creature just beyond my sightline. / I mark our lyric time unhanded,” (“Blue-brown Morning, I Step Though Common Starlings”) is a line that articulates signatures of time, and how these might slide, another interest animated in the book. This poem was written on the winter set of a indie horror film in Joelton, TN, and shivers in its emotional cadence.

Also, signatures present on a contractual document that articulate devotion and/or power figure; the presence of the hand of each party that reifies an understanding or agreement. In the book, epithalamia hold the signing in ceremony. “We release our signatures like horses failing their bits,” is spoken in “Receiver,” the penultimate poem. Lifting off at the end of the book with a love poem is a decision to highlight the power of a bond that brings a person alive and makes them feel known and accepted.

Two Signatures was recognized with the 2023 Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry and is being published by the University of Utah Press. I would like to express deep gratitude to the judge, Joan Naviyuk Kane for recognizing my work’s rigor and imagination. In the spirit of my early discoveries with sculpture and clairaudience, it is my intention that this book makes space for readers to explore the vulnerability and insistence that mark one’s devotion to creative exploration.

Sara Ellen Fowler is the author of Two Signatures (University of Utah Press, 2024), winner of the 2023 Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry (asselected by Joan Naviyuk Kane). A recipient of a 2023 California Arts Council Individual Artist Fellowship, Sara holds a BFA in Fine Art from Art Center College of Design and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of California, Riverside. Publication credits include: The Offing, X-TRA Contemporary Art Journal, Gigantic Sequins, and Cream City Review, among others.

Sara Ellen Fowler is the author of Two Signatures (University of Utah Press, 2024), winner of the 2023 Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry (asselected by Joan Naviyuk Kane). A recipient of a 2023 California Arts Council Individual Artist Fellowship, Sara holds a BFA in Fine Art from Art Center College of Design and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of California, Riverside. Publication credits include: The Offing, X-TRA Contemporary Art Journal, Gigantic Sequins, and Cream City Review, among others.

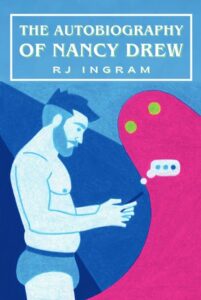

What the Original Authors are Saying

When I sat down to write the first Nancy Drew book my father Carson Keene had just passed away. Nancy was an opportunity for me to continue our adventures. Now after almost 100 years her adventures  continue. The Autobiography of Nancy Drew is one of the many adventures I had no part in creating. The poet uses Nancy & dozens of other “divas” to investigate his own relationships & struggles w/ the tools of a great detective: patience, a keen eye & a tall glass of presumption. The Autobiography of Nancy Drew opens w/ a dedication to the poet’s recently deceased mother who putters in a handful of times throughout the book. However, framing this collection of sonnets & thirst traps (whatever that means!) as both odes & elegies might better equip the reader for doing their own investigating. I’m glad Nancy’s stories are still being told & I encourage the author of The Autobiography of Nancy Drew to read a few more of them!

continue. The Autobiography of Nancy Drew is one of the many adventures I had no part in creating. The poet uses Nancy & dozens of other “divas” to investigate his own relationships & struggles w/ the tools of a great detective: patience, a keen eye & a tall glass of presumption. The Autobiography of Nancy Drew opens w/ a dedication to the poet’s recently deceased mother who putters in a handful of times throughout the book. However, framing this collection of sonnets & thirst traps (whatever that means!) as both odes & elegies might better equip the reader for doing their own investigating. I’m glad Nancy’s stories are still being told & I encourage the author of The Autobiography of Nancy Drew to read a few more of them!

-Carolyn Keene, author of The Nancy Drew Mystery Stories

* * *

The last time I read a sonnet America was openly at war & smoking was good for you. When my dear friend & collaborator Carolyn Keene sent me a copy of The Autobiography of Nancy Drew inscribed w/ “What do you think, Frank?” I thought I was once again falling for a Nigerian Prince scam. Alas it was not a scam, but just a collection of poems. Fine poems. There was one about Baba Yaga on holiday that I quite enjoyed. But the whole time I kept asking “Where’s Nancy?” I asked Carolyn for help & she wrote back (the imaginary still send letters) “Read it again.” So I did & on the second read through I stopped looking for Nancy & started to pretend I was her. Sharp, smartly dressed, bursting w/ questions. And there she was! All of us become detectives when those around us die, the literary fiction industry is sure of that. And w/ every loss each of us gets closer & closer an understanding of who we really are. I very much liked what I found when I got there, if only I had a cleaner map to help me along the way.

-Franklin W. Dixon, author of The Hardy Boys Mystery Stories

* * *

Unavailable for comment.

-Edward L. Stratemeyer (1862-1930), creator of Nancy Drew & The Hardy Boys

THE SUITE WITH THE YELLOW HAT

VII THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAT

RETURNS FROM A WORK TRIP

She cuts her hair w/out a mirror in a cabin

Aboard a large boat named after Calypso

The tin panel reflects enough of a face

Torn & ran to rags barely woman anymore

The Hat remains her only clean feature

Propped up on the bed a secret lover

Nearly lost both of them should be happy

But The Hat only knows as much happiness

She allows it & tonight they drink bitter

Water & eat stale smuggled crackers

She nearly lost The Damn Thing yesterday

In a series of events drawn like illustrations

She came to Africa looking for trophies

Curiosity sleeps all tied up under her bed

VI The Woman With The Yellow Hat

Sleeps Through Boarding

The same dream: floating alone in a raft

In an infinity pool on the roof of a hotel

Cheap champagne rains down like darts

The glass surface disrupted like war zones

Ink blots fill the balloon less sky & men

Can be heard arguing about micro-dosing

Or micro-aggressions you can’t really tell

It’s one of those dreams where the smells

From the pretzel stand seep in like an Evil

Twin hair pinned to the side just the way

You try to do yours & she’s eating her way

Thru an artisan sourdough masterpiece

A kind they would never sell at airports

The beast spits gin right into your mouth

V THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAT

CRASHES YET ANOTHER BIRTHDAY PARTY

Sneaking into a party is easy w/ a monkey

Everyone wants to see you perform tricks

You oblige the little ones until they grow

Tired & bored hey! try to mingle w/ adults

Mr Martini makes chitchat about weather

A topic only Long Island Iced Tea indulges

Rum & Coke want to ask about monkeys

As if you’re some kind of fancy authority

You tell them monkeys can be dangerous

The horrible legends & stories are all true

Someone says they knew a man’s monkey

Wreaked havoc on an entire subway car

Yours looks like he wants to go after cake

The same party: always leave after cake

IV THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAT

CAN’T HELP BUT FEEL A LITTLE AFRAID

The big city tucked into bays a fitted sheet

Men circle along the park sidewalk riddles

Drip out of their mouths the way precut

Proceeds a dreaded onslaught of How

Come you ain’t looking this way you’re so

Good looking but whey don’t you wear

Makeup god you’re just another tease real

Classy ignoring Do You Know Who I Am?

Mr Who I Am retreats after a year or so

His lot in life is to be condemned writing

The same obscenities at more woman

Your monkey does nothing to stave his calls

If anything monkey encourages behavior

Best suited for greasy dive bar bathrooms

III THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAT

PASSES TIIME WITH YET ANOTHER GAME

OF LOTERIA

The Barflies have been staring at The Hat

Like a trophy to be won at a carnival game

A stetson w/ a secret the color of fictional

Lemonade mere cartoon of hat & woman

I used to let men win me prizes like the hat

Would let them toss rings until the bottles

Topple onto linoleum wet w/ carney piss

Would watch guns squirt right into the eye

Now the monkey is keeping men at bay

Frolicking too frilly for their grit & grime

I knew he was good for at least something

Like shuffling packs of cards & cockblocks

The lady passed a cemetery & finds herself

Do not miss me sweetheart: Hat of Queens

II THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAT

EXPERIENCES SEMANTIC SATIATION

When you said monkey all I heard was

Mommy as in the woman who nearly killed

Me before bringing me back to life w/money

For lessons to swim to ski to sail to drive

To type out Shakespeare on a typewriter

For all the shitty things not exchanged

As in the only way I could dress that way

Was to join a monastery bc even monks

Get more action bc keys evolved from cage

The same way many still deny our own

Moments alone minutes alone minuets

To play on the church basement piano

Listen I know the woman you’re talking

About the small one who refuses to smile

I THE WOMAN WITH THE YELLOW HAT

FREES HERSELF FROM SLEEP PARALYSIS

The room shut off stacked like candles un-

Ignited yet the smell of cream & berries

Seeps in thru wax dripped on the dresser

Can he smell them? the golden monkey

A visitor his slant nose cut as if w/ twine

No which is why he presses his black hand

On my chest so much weight so much fire

In his sexless eyes as try as I try to scream

My body to wake but I cannot yell just spit

Gurgle & spit until sleep the monkey still

Presses his tiny spider hand that weighs

On like a stack of stones a cairn carried

Here from the bottom of the mountain

A stone for every moment stacked until

During the height of the pandemic, when the days were dull, anxious, and cloistered, I

found myself casting around for something that would scratch a particular itch in my brain,

an itch for short, pithy bursts of emotion. Twitter could reliably do just that, but the

emotions it provoked were always anger and anxiety. Frankly, I was generating quite

enough of that on my own. No, I needed something else, something that would jolt me out

of my brain’s circular patterns.

Then I remembered poetry.

If you’re like most people, you probably don’t read much poetry. I’m a poet, and I read less

than I would like. But poetry deserves a place in your reading life beyond the special

occasion moments (think weddings and funerals) when nothing else will do. Poetry offers a

hyper-distilled reading experience: sharpened linguistic and imagistic focus combined with

a crystalline burst of insight, observation, or clarity.

In those dark days of the pandemic, it was poetry that offered a respite from the circularity

of my own thoughts, served up in small doses that were perfect for the short-attentionspan

mood of that moment. And, as I researched and wrote Accountable, it was poetry that

gave form to the feelings and questions that I was still trying to bring to the surface of my

understanding.

I’ve written here about the thoughts and techniques that informed one of the poems that I

wrote for the book, Four Kinds of Justice. But today I’d like to share a few of the poems that

shaped the book as a whole.

Every book I write gets a dedicated notebook in which I scrawl everything from my

thoughts as I’m working to my lists of people I need to call. I also tend to add ephemera that

feels relevant, like the two fortune cookie fortunes you see here, which embody the forking

paths posed by the racist Instagram account: appearance vs. character.

The initial pages of my notebook for Accountable includes quotes from Hannah Arendt,

Jamelle Bouie, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Jia Tolentino, James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, and

Isak Dinesen, as well as business cards from people I had interviewed, lists of experts to

call, books to read, and similar cases to investigate.

The first poem I pasted into the pages was this one by Emily Dickinson:

After great pain, a formal feeling comes –

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs –

The stiff Heart questions ‘was it He, that bore,’

And ‘Yesterday, or Centuries before’?

The Feet, mechanical, go round –

A Wooden way

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought –

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone –

This is the Hour of Lead –

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow –

First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go –

The Hour of Lead was a title I considered for the book, as it summed up the state I found so

many of the young people in when I first met them. The poem beautifully encapsulates the

numbness that follows trauma, using words like ceremonious, still,

mechanical, and Wooden to conjure the way that those who had been targeted by the

account went through the motions of returning to school and “moving on,” without actually

being able to do so. I was struck by the out-of-body sensation of those mechanical Feet

traveling “Ground, or Air, or Ought,” not knowing if they were moving across solid surfaces,

dreams, or obligations. And, I hoped, there would be an end to this phase, remembered

eventually (if outlived) in stages: trauma, numbness, and eventually, recovery: “First – Chill

– then Stupor – then the letting go –”

But how long would it take to get there? The girls who had been targeted were still in the

chill and stupor. Neither they, nor I, had a map for how they might let go.

The next poem in the journal is Rita Dove’s incisive “Pedestrian Crossing,

Charlottesville,” which captures the varying lenses a Black observer uses when observing

the antics of a group of young white people while simultaneously taking stock of their

latent power and capacity for harm.

Pedestrian Crossing, Charlottesville

A gaggle of girls giggle over the bricks

leading off Court Square. We brake

dutifully, and wait; but there’s at least

twenty of these knob-kneed creatures,

blond and curly, still at an age that thinks

impudence is cute. Look how they dart

and dither, changing flanks as they lurch

along—golden gobbets of infuriating foolishness

or pure joy, depending on one’s disposition.

At the moment mine’s sour—this is taking

far too long; don’t they have minders?

Just behind my shoulder in the city park

the Southern general still stands, stonewalling us all.

When I was their age I judged Goldilocks

nothing more than a pint-size criminal

who flounced into others’ lives, then

assumed their clemency. Unfair,

I know, my aggression—to lump them

into a gaggle (silly geese!) when all

they’re guilty of is being young. So far.

The poem lyrically and meticulously documents the layers of annoyance, generosity, fury,

and self-protection that Dove feels while watching these gamboling girls in the wake of the

white supremacist violence in Charlottesville. While researching the racist Instagram

account and its aftermath, which took place in the same time period as the violence in

Charlottesville, I watched Black parents wrestle with these same emotions. Was each

person who followed the account a “pint-size criminal/who flounced into others’ lives,

then/assumed their clemency?” because they believed “impudence is cute?” Were they

simply “guilty of is being young?” Or was the present misdeed a prologue to something

even worse? The deep wariness and weariness captured in the last two words of the poem

hits hard. So much history summed up in those words. So many lessons learned the hard

way.

As the reporting process continued, my notebook filled with poems about the beauty and

power of girls, and about all the ways that this beauty survives despite trauma, misogyny,

and misogynoir. One of the hardest thing about researching the book was seeing how the

bright flames of the young women who’d been targeted by the account had been dimmed

by the experience.

Here’s a note I wrote after a conversation with one of them:

“I get off the phone feeling broken-hearted. [X] is such a spark, so beautiful and funny and

smart, and she remains flayed by this experience.”

That call brought to mind these lines by Sonia Sanchez, which I also scribbled in my

notebook:

there is no place

for a soft / black / woman.

there is no smile green enough or

summertime words warm enough to allow my growth.

It was for this reason, I think, that I began pasting in poems that celebrated survival and

resilience. Alison Luterman’s Some Girls, for instance:

Some girls can’t help it; they are lit sparklers,

hot-blooded, half naked in the depths of winter,

tagging moving trains with the bright insignia of their

fury.

I’ve seen their inked torsos: falcons, swans, meteor

showers.

And shadowed their secret rendezvous,

walking and flying all night over paths traced like veins

through the deep body of the forest

where they are trying on their new wings,

rising to power with a ferocious mercy

not seen before in the cities of men.

Having survived slander, abuse, and every kind of exile,

they’re swooping down even now

from treetops where they were roosting,

wearing robes woven of spider webs and pigeon

feathers….[follow this link to read the rest]

Again and again, I found myself drawn to poems about overcoming, about girls who refuse

to be defined by those who don’t see their beauty and their magic, like Barbara Jane

Reyes’ ‘Track: “A Girl in Trouble (Is A Temporary Thing),” Romeo Void (1984)’:

Brown Girl Sings Whalesong

When they say you are as big as a lumpy, blubbery whale,

you may go ahead and bellow deep. Creak,

croon, and trill, moan low. Go ahead, open your mouth so wide, that

you can swallow the sea. Know that your blood pulls you through

what your oldest ancestors committed to heart. Remember

you have touched the ocean floor, and you have made your garden there.

Remember, your skin is thick. Remember, no one has tamed you.

Yes, you are immense, your lifespan and memory long,

your heart larger than a full-grown man. Your lungs carry air for us all.

Your ribcage could be a refuge. Your skull is a cavern of deep song.

Through murk and poison, you move true with the moon.

Your body lights a million lanterns. Your deep pitched song finds your sisters,

your mother. They say the earth’s most unruly parts sing like you.

Poems like these were sustenance for me during the years I worked on the book. I needed

their visions of female power and resilience, needed to be able to picture how the young

women I was writing about might be when they reached the other side of this experience.

And all this time, the girls themselves were still in the deep freeze that Emily Dickinson

describes. There were times when their despair and their feelings of powerlessness almost

convinced me that they would never emerge.

In the end, I chose Tracy K. Smith’s We Feel Now A Largeness Coming On as an epigram to

the book because it so gorgeously captures the process of becoming mighty in the wake of

being shamed, of finding the power to take up space in a world that wants to shrink you

down to nothing. The book uses the first lines of the poem as its epigram, but I want to

leave you with the last ones:

. . . What Black bodies carry

through your schools, your cities.

Do you see how mighty you’ve made us,

all these generations running?

Every day steeling ourselves against it.

Every day coaxing it back into coils.

And all the while feeding it.

And all the while loving it.

New York Times-bestselling author Dashka Slater has been described as a “triple threat” for her success in journalism, fiction, and children’s literature. The author of fifteen books of fiction and nonfiction for children, teenagers, and adults, her work has been translated into more than fifteen languages and has won numerous awards, including the

2024 J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize from the Columbia Journalism School and Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for her nonfiction narrative, Accountable, the 2023 Kurt Vonnegut Speculative Fiction Award for her short story, “The Jeanines of Summer,” and the 2018 Wanda Gág Read Aloud Award for her picture book, Escargot. A 2024 Pushcart Prize nominee and the recipient of a 2005 Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, Dashka is a frequent speaker at schools, conferences, colleges, and universities. She lives in Oakland, California and teaches at Hamline University’s MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults program. Learn more at www.dashkaslater.com.

WHY DECIDED TO WRITE MY MEMOIR AND SHARE MY STORY

by Rosa Lowinger

A version of this essay was published on October 10, 2023 in Women Writers, Women’s Books.

In 2009, I was a Rome Prize Fellow at the Academy in Rome, researching the history of vandalism to art and public places. I had spent three decades working as a conservator of art and architecture, and I finally had time to write and think about a topic that was vexing me constantly- why people deliberately damage things of value.

Day in and day out I pondered the duality of damage and repair. Was there a common thread between unauthorized attacks on works of art? A connection between graffiti and the systematic destruction of monumental Buddhas, mosques, synagogues and churches? One day, while prowling through the Academy’s library, I came upon Primo Levi’s memoir “The Periodic Table.” Primo Levi was an Italian Jewish chemist who had written several books about his time in Auschwitz. The Periodic Table used his work as a chemist was an organizing metaphor for telling stories about his ancestors.

I was immediately struck by Levi’s book, and excited by the possibility of using the same structure for a memoir about art conservation. No one in my field had ever done this before. Those of us who repair works of art occasionally show up in fiction; but we’re mostly depicted as part-time sleuths, or spies, or dewy-eyed ingenues who succumb to torrid passions with the owners of old master canvases. We are clichés in literature, but none of us had ever tried to counter those narratives by penning a memoir of our own about the way we think, plan, approach a treatment, or manage limitations. Levi’s book was the perfect model. Now all I needed was to tease out what the story was going to be about.

My first published book Tropicana Nights: The Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub had been a sort-of memoir. Written with Ofelia Fox, the octogenarian widow of the famous cabaret’s owner, it told the history of 1950s Cuba, the time and place where I’d been born, through the lens of its most glamorous performance venue. My editor, Tim Bent at Harcourt, suggested that I weave my relationship with Ofelia into her stories about dazzling nights of mambo, Celia Cruz, and mobsters in the place known as the “Paradise Under the Stars.” Ofelia’s so-called “housemate” Rosa Sanchez liked to hover around us as we worked, pouring martinis and coyly steering my inquiries away from anything that touched upon the well-documented fluid sexuality of Tropicana’s denizens.

Just as we got to the end of the writing, Ofelia and Rosa trusted me to tell the truth about their four decades of love and devotion to each other. “People can be more than one thing,” Ofelia explained sagely. “I just needed to be sure we could trust you.”

Around the time that Tropicana Nights came out, my 25- year marriage fell apart. So did my relationship with my business partner- the third such failure in two decades. I left for Rome, fell in love again, and started a new conservation practice upon returning to Los Angeles. Eventually RLA Conservation, LLC became the largest woman-owned conservation firm in the United States, and the only one Latina-owned.

Then, in 2019, my father died. Six months later, the world went into lockdown. To fill my days that summer of the virus, I began writing a novel about 1950s Havana. A fictionalized version of the Tropicana story, Paradiso Cabaret’s main characters are a showgirl who was been raised in an orphanage under destitute conditions, and a Romanian Jewish immigrant to Cuba who trained as an art restorer in 1930s Rome. One day during the dark days of the lockdown, I realized that the showgirl and the art restorer were stand-ins for my parents. Their fraught backgrounds and tumultuous marriage formed the emotional core of the novel. My father had wanted to study architecture in Cuba, but his Romanian immigrant father refused him. My fictional art restorer had his heart and personality.

Every night during the years of the pandemic, I ‘d call my widowed mother in Miami. She’d wail, beside herself: “I am alone, alone! No one cares about me. My life is worse now than when I lived in the orphanage!” She kept repeating stories about her terrible days of trauma. One of the most vivid was about having to clean 10 marble tables each day in the orphanage.

One morning, I wrote the words, “A five-year old’s hand drags a soapy rag across a marble table.” And then: “I, too, am an expert in cleaning marble.” That was the beginning of Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair, a book in which I explore the way repair of the material world can provide guidance for personal and societal healing. Last summer, before Dwell Time was published, I workshopped Paradiso Cabaret I am back to writing about paintings conservation in 1950s Havana.

Rosa Lowinger is a Cuban-born writer and art conservator working in Los Angeles and Miami. A Fellow of the American Institute for Conservation and the Association for Preservation Technology, Rosa was awarded the 2009 Rome Prize at the American Academy in Rome to research the history of vandalism to art and public space. Rosa’s books include Tropicana Nights: The Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub (Harcourt: 2006), Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure, American Seduction (FIU Press, 2016), and Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair (Row House: 2023), winner of the American Institute for Conservation Kress Publication Grant and recipient of a Kirkus starred review. Short stories include Repairing Things and Buried Treasure for Bridges to Cuba, published by University of Michigan Press, and The Empress of the Waves for Una Isla en La Luz (TraPublishing: 2017). Her first play The Encanto File, was produced in 1991 by the Women’s Project and Productions at the Judith Anderson Theater and published in Rowing to America and Sixteen Other Short Plays, edited by Julia Miles (Smith & Kraus, 2002). Rosa is the author of the 2023 Lithub essay Life as a Conservator: Learning to be Grateful for Failure and many articles on Cuba, art conservation, vandalism, and contested monuments. She co-curated Concrete Paradise: Miami Marine Stadium at the Coral Gables Museum (2013), and Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure, American Seduction at the Wolfsonian Museum. Rosa’s work has been featured in dozens of magazines and newspapers, including a November 3, 2023 feature in The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town.

Rosa Lowinger is a Cuban-born writer and art conservator working in Los Angeles and Miami. A Fellow of the American Institute for Conservation and the Association for Preservation Technology, Rosa was awarded the 2009 Rome Prize at the American Academy in Rome to research the history of vandalism to art and public space. Rosa’s books include Tropicana Nights: The Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub (Harcourt: 2006), Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure, American Seduction (FIU Press, 2016), and Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair (Row House: 2023), winner of the American Institute for Conservation Kress Publication Grant and recipient of a Kirkus starred review. Short stories include Repairing Things and Buried Treasure for Bridges to Cuba, published by University of Michigan Press, and The Empress of the Waves for Una Isla en La Luz (TraPublishing: 2017). Her first play The Encanto File, was produced in 1991 by the Women’s Project and Productions at the Judith Anderson Theater and published in Rowing to America and Sixteen Other Short Plays, edited by Julia Miles (Smith & Kraus, 2002). Rosa is the author of the 2023 Lithub essay Life as a Conservator: Learning to be Grateful for Failure and many articles on Cuba, art conservation, vandalism, and contested monuments. She co-curated Concrete Paradise: Miami Marine Stadium at the Coral Gables Museum (2013), and Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure, American Seduction at the Wolfsonian Museum. Rosa’s work has been featured in dozens of magazines and newspapers, including a November 3, 2023 feature in The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town.

ON TITLES

by Jaclyn Moyer

I can no longer remember when I first gave a name to the manuscript that eventually became On Gold Hill, only that at some point midway through what would turn out to be a decade-long process I gathered up an unwieldy assortment of material— half-finished essays and sketches of scenes, lists of questions and passages quoted from other books— corralled them all into a single Scrivener document, and labeled the file: “On Wheat.”

At the time, I didn’t think of those two words as a title, more of a framing device to guide the contents that made its way inside the document. Nor did I consider the document to be a book. Instead, I thought of it simply as a project. Had I set out to write a book from the beginning, I almost certainly would have been too daunted to proceed. But a project I could undertake. A project had no definitive end point, no expected output, but was instead expansive, experimental, process-oriented. A book was a thing one made, while a project was a thing one did.

For the bulk of the ten years I worked on On Gold Hill, this way of thinking served me well. It kept me writing through periods of intense uncertainty, kept me at my desk in the throws of self-doubt. (It didn’t matter that I could not write a book, because I was not trying to write a book, I was just working on my project.) But at some point, when I had a completed narrative and was ready to have other people’s eyes on it—mentors and readers, potential agents and editors—I had to start thinking of “the project” in more concrete terms. Though it was well over 100,000 words, the prospect of calling it a book felt no less unnerving than ever, the noun struck me as both intimidating and pretentious at once. So I got comfortable instead with the word “manuscript.” A manuscript, like a project, exists in-progress, unfixed. A manuscript did, however, need a name.

At first, I considered sticking with “On Wheat.” After all, it had been there, faithfully heading the document all these years, and seemed deserving of a promotion to title. I liked the classic simplicity, how it payed homage to the essay tradition, they way is suggested an act of turning this one thing—wheat—over and over in ones hand to examine it from all angles.

My early readers did not agree. “You can improve the title, I think” wrote one.

“What will you call it?” asked another, to whom I replied, “The title is on the manuscript.”

“Oh, I guess I didn’t see it.“ She said.

“Its on the first page.”

“Where?”

“Right there,” I pointed to the words On Wheat, centered in the title position at the top of the page.

“Oh,” she said, and then, “That’s it?”

I began to cast about for a new title. One day, while reading about wheat morphology, I came across a passage describing the distinctions between various plant parts. “Roots,” a sentence read, “are underground organs.”

I wrote those words out on a sticky note and stuck it to the wall over my desk. Roots Are Underground Organs. That’s it, I thought, that’s my title. I liked the way the fact, out of context and isolated in that way, read like poetry. It fit the genre of my book—which was partly a heavily researched inquiry into aspects of the history of agriculture, and part-memoir—and it alluded to the main theme of a search for heritage. I erased “On Wheat” and replaced it with those four words. And for a few years, they remained.

But at some point the manuscript seemed to squirm out from under this name too. The title no longer fit in the way it once had, it struck me now as too narrow, too specific. Though it had come to me unsolicited from the pages of that textbook, it now sounded to my ears as contrived, over-wrought.

I erased the title, reverted once again to “On Wheat.”

It was in the course of another revision, that I found what I believed was the true and most perfect title of the project. The line was right in front of me, in a passage I had written about advances in plant breeding at the start of the 20th century: Laws of Inheritance. For one, those three words strung together just sounded like a title. The line had that solid, full ring to it. But it was the double meaning, the deft joining together of the two threads of the manuscript that I found most beautiful. In one sense, the phrase evoked the project’s central questions: How are we bound by our personal and collective histories? What does it mean to loose, or to regain, ones heritage? In another sense, it referred to Gregor Mendel’s Laws of Inheritance, the groundbreaking biological theory that described, for the first time, the workings of genetic inheritance thus forever changing the trajectory of plant breeding and agricultural development.

I imagined the satisfaction a reader would feel, mid-way through the book, when she encountered the passages about Mendel and the second meaning of the title emerged. I imagined it would feel like the moment when, looking at one of those duplicitous images, what had been a duck suddenly becomes, with a shift of perspective, a rabbit.

I erased “On Wheat” and placed “Laws of Inheritance” at the top of the manuscript, where it remained through the process of finding an agent and, later, a publisher.

Over the many months my editor and I worked on final trims and revisions to the manuscript, we didn’t talk about the title. Though I’d been warned that editors tend to have a lot to say about titles, I assumed she, and everyone else at the publishing house, found mine just as perfect as I did. It remained on the title page as I made my last revisions in the weeks before we planned to transmit the manuscript to the production team, after which no more substantive changes could be made.

The date of this transmission loomed large in my mind. If I thought about it too much, it terrified me. For this would mark the moment when this thing that had been for so many years a malleable, fluid, work-in-progress would harden into its final and fixed form. Like a clay pot entering a kiln, I knew once we transmitted the pages to the production team, outside of fixing errors or typos, they would no longer be changeable.

A week or two before the deadline, my editor wrote to say the marketing and publicity team had some issues with the title. They found it too abstract, not evocative enough, not compelling. In short, they wanted something different.

At first, I pushed back. Maybe they just didn’t understand the title, after all not everyone had read the manuscript. I explained the double meaning, how it alluded to the central themes and to the history of plant breeding. They were not impressed. A title, they explained from the marketing perspective, had to do its work before a word of the book had been read. It didn’t matter if, halfway through the book, it’s meaning was suddenly revealed in a satisfying way: If a title failed, a reader would not get halfway through the book because she wouldn’t pick it up at all. A title must pull a reader in on its own.

I remained convinced. In part, I couldn’t get behind this idea because I still wasn’t ready to conceive of what I’d made as a book, to imagine it as an object on a shelf. Though the words would, of course, come at the very beginning, choosing the final title, I realized, was for me a kind of ending. Each of the former title iterations had served its time before eventually sloughing off like a shed skin, allowing space for the manuscript to grow, to change shape. But this one would remain, sealing the manuscript into its present form, transforming it from a fluid project to a static book.

Up until this point, the practice of writing this manuscript had been, foremost, a form of inquiry. From sketching the first scenes, to wandering the winding corridors of research, to puzzling out the structure, possibilities abounded. Even the last line edits offered up unexpected insights: While searching for a better adjective to replace one that didn’t land quite right I recalled a long-forgotten memory of my childhood home; when I called my Dad to fact-check a detail about the car he drove when he met my mother, the question sent him down a rabbit hole of memories and I found myself listening to family histories I’d never before heard; in re-writing a clumsy sentence, I arrived at a deeper understanding of the idea I was trying to express. Each time I read the manuscript, something new emerged, revisions were called for: how could I consign the project to an unchangeable state? I thought of a taxidermyed animal, a once-living creature rendered stiff and glass-eyed.

The days ticked by and I could not come up with a new title. My editor and I bounced ideas back and forth, some seemed to have potential but then, a day later I’d read them again and cringe. Nothing fit. The deadline loomed. I could not bring myself to settle on a name.

One day, with a flurry of unsatisfactory titles swirling in my thoughts, I took a tablespoon of sourdough started from the jar on my counter and began to mix a leaven. Perhaps baking bread would clear my head. For the past 15 years I’d made sourdough bread every week. At times, I’d baked professionally in batches as large as 120 loaves per day. Other times, I’d made only enough to last my family the week, three or four loaves.

The act of choosing a title, it occurred to me as I coaxed water into flour with my hands, reminded me of cutting the slash into an unbaked loaf before loading it into the oven. After the two-day process of preparing the dough—the precise measuring of flour, water, salt; the long bulk fermentation; the careful stretches and folds; the shaping; the second rise—the slash marked final moment in which my hands would alter the outcome of the bread. It was a small thing, yet it would have significant consequences for the final loaf: the depth and shape of the cut would dictate how and where the dough would swell as it rose, defining not just its outer appearance—the ears and pattern of the crust— but also the internal crumb structure. It was a swift action, occurring in less than three seconds, but its mark on the bread would be indelible. Titling my manuscript felt similar: it marked the last tweak, the final touch before things were out of my hands and what had begun as a blank page—all possibility—would become only exactly what it was.

This comparison sent a quake of nausea through my gut. Immediately I recognized the feeling: when I first started selling bread, each time I slashed a round of loaves and loaded them into the oven, a similar wave of anxiety filled me as I waited to see the bread in its final form, to pull the loaves out of the oven and slice a serrated knife through the crust to inspect the crumb. When a bake disappointed me—a batch left to ferment too long turned out flattish and overly sour, or another, proofed at too cool a temperature failed to fully swell in the oven, the crumb uneven and overly chewy—I was devastated, furious and overcome with a sense of failure. I determined to avoid this feeling by getting better, by mastering every aspect of bread. But as my skills as a baker increased, so too did my standards: I could not avoid disappointment.

The only way out of this mental minefield, I found, was to focus not on the outcome but on the process. Though each loaf I pulled from the oven had reached its final and fixed form, the larger project of baking remained a work-in-progress. Saturday’s loaves, imperfect as they might have been, would be eaten and soon enough next Thursday would roll around and I’d take my starter out of the fridge, feed it with warm water and fresh flour, and begin again. The starter itself evidenced the ongoingness of the process, a through-line that threaded each loaf to the ever-evolving practice of baking bread.

Perhaps I could think about writing in these same terms. A book had an endpoint, a final form, but the larger project continued. Of course I would look back upon these pages in a year—or five, ten—and see them differently, find them imperfect, riddled with changes begging to be made. But maybe that wasn’t evidence of fault, only proof of the ongoing evolution of myself and my work as a writer.

With only a few days remaining before the deadline, I considered again what my publishing team had advised: a title must do its work before a word of the book is read. It must compel a window shopper or library goer to pause, must evoke an image or feeling or question, must, as one writer told me, promise something.

I wrung my brain for ideas, to little avail. I wrote out the names of my favorite books—The Far Field, Lila, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Salvage the Bones, The Grapes of Wrath. This, I found, was equally unhelpful: Once I’d read a book, I could no longer read the title without hearing echos of the book itself, could no longer imagine what effect the words might have had on their own.

So I rode my bike to the library and walked the stacks, reading spine after spine. Some titles were poems in themselves: A Heart is A Muscle the Size of a Fist, others just a stark word or two: Aftershocks. The Orchard.

I wrote lists of possible ideas that spanned the spectrum from a sentence (Every Seed Contains a Root) to a single word (Diaspore) to actions (Saving Seed). I tried the classic phrasing of The ____ (The Common Field). I sent my ideas to my editor, and she shared hers. At some point the phrase “Gold Hill” entered our list. This was the name of the region where most of my manuscript was set. I recalled a piece of writing advice I’d once been given: When stuck, start in place. It was a trick I’d used over and over in the course of writing the manuscript. Perhaps this could work with the title, too. Perhaps “Gold Hill” was the place to begin. Still, something about this name wasn’t quite right, lacking somehow. My editor suggested “Grown on Gold Hill,” but this sounded to me more like a marketing slogan for regional produce than a literary title. So we scratched “grown” to find ourselves left with, simply: “On Gold Hill.”

I did not immediately love this title. There was no ah-ha moment, no instant feeling of “yes, that’s it!” It was not earth shattering, not even particularly catchy or poetic. It did, however, evoke something. It prompted a bit of wondering, some intrigue. All this pleased my publishing team, but what I found most compelling about “On Gold Hill” was the way those three words formed an incomplete sentence, one in which the ending remained unwritten. In place of resolution, it offered only possibility.

GROWING UP IN CHICAGO HOUSE MUSIC

by Marguerite L. Harrold

This essay appeared originally in the February 3, 2020 issue of Chicago Review. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Some people go to church, I go to the disco. I was baptized by Chicago house music back in 1983. Yes, I am a heathen, in the purest sense.

For those of us who live in it, those of us who were born in Chicago between 1964–1980, house music was an ever-present staple on Saturday night radio. If you were too young to get into a club, WBMX, Saturday Night Live, Ain t No Jive, Dance Party, featuring “The Hot MIX FIVE,” was the club. Me and my cousin Carol would turn up the radio and practice our best moves. Grandma Gert would peek her head in and sometimes come in to show us how to really get down. Sometimes a group of us were all hanging around, sitting on somebody’s car, in Markham, IL, and the mixes would start. All of us would be dancing in the street. It was a party.

By the time I turned fourteen, I was allowed to go out to Markham Skating Rink on Saturday nights. A friend named Derrick would shuttle carloads of us back and forth. There was a tiny little disco, with an even tinier dance floor in the back of the rink that played some of the best house music I’ve ever heard. I couldn’t really dance back then, but I had to be there.

Some of these dancers had Soul Train moves, I mean twists and kicks and the high jump kick and twirl! People made a circle, taking turns, one at a time, showing off what they could do. Sometimes they turned into battles, not as aggressive as break-dance battles, which were also happening then. These were more sensual and stylistic. I never reached that level, but there was a point, when a song dropped, where everyone got on the floor and the place was so small, there was no wall to stand on. You just got swiped up and you had to move something. Our bodies were so jammed together, it was easy just to follow the beat of the one in front and the one in back of you. Sometimes I was sandwiched between two boys and sometimes it was two girls. Yes, there was humping, but it wasn’t lecherous. It was just people, eyes closed, hips pumping, swaying, hands in the air, high on the rhythms in the music. You felt that beat from the ground up.

When an older friend, Johnny Williams, told me about this place underground that played the best house music he’d ever heard, I had to go. I was fourteen and the party didn’t even get started until 2 a.m., and it was in the city. It was The Muzic Box on Lower Wacker Dr. and South Water St. It was literally a long black box, with nothing but a strobe light, steam, and bodies moving. I had to sneak out. I went to the Muzic Box a total of six times, each time grounded for a month, but it was worth it. Eventually, I learned how to “spend the night at a friend’s house.” When I met Honey Dijon in high school, she took me to all the house music parties at The Playground, The Power Plant, Club LeRay, Medusa’s, and Smartbar. By that time, I was completely obsessed.

House music validated my experiences as a Black person, as an oddball, as a bisexual, and as a human being. The music put my pain into healing song. The songs reflected love lost, liberation, and freedom. The people, mostly Black gay men, were welcoming and supportive. They cared for me as if I was part of the family. Way too young to be in the club, they watched me to make sure I stayed out of trouble. I was pretty straightlaced. I didn’t smoke or drink. All I wanted to do was dance to the music.

When I found house music, I found something that my soul needed. I found a space where the anger and pain, the brewing sexuality and violence in me could be soothed. I found a place where the abandoned oddball, the freaky nerd, could be free and accepted. I’d lose myself and find my heaven in a black box in a basement with sawdust on the floor. The center of me, dancing on a speaker, dancing all over the room, with everyone and no one in particular. Just as comfortable in a silky dress as I was in cutoffs, a Fishbone T-shirt, and five-holed, steel toe Doc Martins. I was there for the music. To dance and sweat until it ran down my face like a sun-shower. Until my arms and legs felt like wet noodles. Stop. Drink water. Repeat.

Born in Chicago, house music is the granddaughter of gospel and soul, the daughter of disco and blues, the sister of jazz, funk, and new wave. Her children are techno, freestyle, jack, juke, trip-hop, EDM, trap, and all the others who claim her.

House music originated at The Warehouse circa 1977. It was created by Black gay men. Combining city innovations, southern roots, and African heritage, it was a culture within a culture, yet it was not exclusionary. If you knew where the party was, you were welcomed in. Come as you are. Wear what you want. Be as you are or who you want to be. At a house music party, everyone is a freak and all the more precious for it. House music is what we want to be in the world and how we want the world to be.

Originally, house music was not necessarily about resisting or restructuring the dominant culture. It was about creating a space where Black gay men and other gay men of color could be free, safe, and expressive among themselves. It was a communal space, a safe haven in Chicago, which was often oppressive and repressive of gay and Black people. White gay culture was not accepting of Black gay men, despite a common otherness. Black gay men were often required to present three forms of identification in order to gain entry into North Side white gay clubs. It was necessary for Black and Latino gay men to create spaces of their own. In doing so, they made spaces for all of us. The music quickly spread throughout Chicago, New York, London, and Detroit.

Different from house music in London or New York and from the rave scene, Chicago house music was not about drugs. The music is the drug itself, and in Chicago it is the drug of choice. The feeling of music moving through you is the kind of euphoria people who do drugs are trying to get. There is an almost surrealist style to the way people move: legs kicking in the air, spinning, back bends, grinding, jacking, and jerking. There is someone with a tambourine, a whistle, a hand drum. To an outside observer it may look ritualistic, tantric; these bodies, this communal art. The energy is so addictive. The release so complete.

House music is ecstatic, in the way a Black Baptist or African Methodist Episcopal church service can be. It is participatory. The bass pops pieces of asphalt up off the street and you feel the music before you even get to the door. The kick drum surges your heartbeat. The cymbals rustle the butterflies in your stomach. It’s rapturous and the waves overtake you. It is the church choir, a juke joint on fire, a sonic tattoo. House music etches itself into your skin. Bodies ribbon together in the savory heat.

Like church, Chicago house music was and continues to be a central force for social interaction, spiritual liberation, and community. For those of us who grew up in Chicago house music, it is very personal. You’ll hear the phrase, “Some call it house. We call it home,” and in Chicago that is the truth. To be called a house head is a badge of honor and a way to locate your own people. Like church, the Black church in particular, house music parties are accepting of all who come through its doors, hear the 4/4 beat, feel the bass coming up from the street into the soles of their feet, and find their body moving.

Like a preacher, the DJ is the leader. The congregation and the crowd feed the service. When the preacher’s sermon causes him to bounce on his heels, the congregation bounces with him and the vibrations shake the room. He calls out his refrain and the congregation responds with an Amen or a Yes Lord. As the choir sings, something within you is released in the rhythm and the assembly of voices. The creaking of the floorboards and the heat of the congregation swaying together, rocking side to side, hands clapping, feet stomping, creating a wave of sound and movement that takes a singular body and pulls it into the collective. At a house party, you will hear the same call-and-response, though it may be a collective, Oooh Shit, or an Alright, or a Hell Yeah. There will be hands raised in the air in praise and eyes closed as bodies move in unison.

If you listen to the lyrics in most house music songs, you’ll see that they are about love and finding peace and freedom. They are about people finding their way out of stereotypical roles, or bad relationships. It’s about coming out, yes, sometimes out of the closet, but in more ways than sexuality or gender identification. It’s about coming out of the walls society has built for us. Songs of triumph over the pain in the world. Songs of loss and grief and survival. Songs that truly represent the Black experience, the gay experience, the human experience, such as “Promised Land” by Joe Smooth:

Sisters, brothers. One day we will be free from fighting, violence, people crying in the streets. When angels from above fall down and spread their wings like doves. As we walk, hand in hand, sisters, brothers, we’ll make it to the Promised Land.

Many house music songs are actually gospel songs, such as “I Want to Thank You” by Alicia Myers, or “I Get Lifted” by Barbara Tucker. People are likely to get the Holy Ghost on the dance floor just as they would in the church aisles, often with the exact same dance moves. In church you shake your neighbor’s hand or hug your neighbor. At a house party, you dance up close, juke or jack your neighbor, or the nearest speaker, body pressed up against it, feeling literal wind from the vibrations of the sound. The Spirit is unleashed in the gathering. People who’ve never met one another hug, smile, give dap, dance arm in arm, sing in unison, and raise their hands in praise. This unifying energy is the essence of Chicago house music.

At a house party, someone either drags you out on the dance floor or the DJ plays a song that has you tapping your feet, and before you know it there are people dancing around you and you are swept up in the crowd. When you go to a house party, you are part of something, not just a bystander. You are part of the creation of the work of art happening at that moment. You are welcomed and encouraged to participate.

House music is a place, a state of being, but it is not tied to any particular venue. A house party can pop off anyplace. It could be in any neighborhood in town, an underground black box room with only a strobe light and steam, a hotel ballroom, an abandoned warehouse, a beach, or a car radio with seven teenagers dancing around it.

The party followed the DJ, no matter where it was. (We still call any house music function a party.) Sometimes a club didn’t even have a name, or it wasn’t quite a club at all, but a restaurant rented out on a slow night, turned into disco heaven. There was a place called Kings & Queens, which was an empty loft space on Lake St., that literally had a giant hole on the dance floor where you could see three stories down. We just danced around it. This spot only lasted a month.

Chicago house music traveled the world and came home to show us all the things she has in her bags. The first time I heard house music played by a live band, I lost it. It was a dream musical collaboration on the level of Kate Bush making a record with Prince, or Anthrax together with Public Enemy. There was Peven Everett and Tortured Soul (from New York) and the New Orleans brass band The Soul Rebels playing an entire set of Chicago-style house music. It was a whole new level of experience. The live drums vibrating against my body, the walls, the floor. An electric bass grooving a house lick. I was filled up and taken over as I watched the room explode with the kind of shared energy that can only be described as spirit.

“Oooh shit,” I said out loud, bouncing up and down, waiting for the bartender. A beautiful, hefty queen my mom’s age looked over at me. “Sorry,” I said, realizing I nearly screamed in her ear. She smiled, laughed, and said, “That’s all right baby. That’s what it’s all about.” She was bouncing too and gave me a big hug before she swished her way to the dance floor.

House music is constantly in motion and ever changing. It is a dynamic art form. It does. It makes. It becomes. It takes hold of your insides and finds brightness. It finds your pain and brings you joy. It finds your weirdo and brings out your sassy, your funky, your truest you. There is freedom and liberation and hope in this music. Created out of marginalization and segregation it continues to bring people of all walks of life together.

To say what house music is can never really be completely accurate because house music means something unique to every person who experiences it. But once it takes hold of you, it will never let you go. And I am truly grateful.

Marguerite L. Harrold is a poet, writer, educator, community activist and ecologist, originally from Chicago. She is the author of Chicago House Music, Culture and Community. She earned an MFA in Poetry from Columbia College Chicago. She is an Associate Editor for Prairie Schooner, and the Educational Promotions Manager for African Poetry Book Fund at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where she is pursuing her PhD in Creative Writing. Her work has been published in Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora, Chicago Review, RHINO, Anti-Heroin Chic and other journals.

WHY PEOPLE HATE MIMES

by Ismet Prcic

Portland. Pioneer Square. Polite precipitation. People.

People just being people: alone, in duos, trios, in groups. Alone people in duos, trios, groups. A larger gathering slowly assembles around the square’s center, eyes up from their I- phones, giving reality a chance. Not a long one. The phones are not off. The phones are still in hand and at the ready, facing up, gaping still. But the eyes are off the screens for the moment.

In the center, on the cement, a street performer. Female, forties, sinew leaching on bone, agile. Sensible loafers, navy blue pants, latitudinally-striped T-shirt, white caked-on face make-up topped with a French beret—a uniform. Eerily make-uped white eyelashes. Three small black triangles drawn upon each cheekbone, each pointing back to the irises, watery blue them. Beautiful. Other face orifices dark places as if hacked and punched into dried papier-mâché face-like surface with angular objects. Keep Portland Weird button where her left boob isn’t, pinned upside down to be weird. An amputee perhaps, or just naturally like that. Only stripes where her right boob isn’t.

She seems to be inside an invisible box, the old popular. Wherever she turns, in every direction, she’s limited by the edges of what people cannot see but it’s really there for her to feel. Despite the fact that the box cannot be seen people can gauge, glean that the box is there. So to speak. She is helping them gauge the borders of where the box ends and reality begins.

I’ll believe it when I see it, people sometimes say, blinking their fallible, human eyes.

__