EDITOR’S NOTE

By Andrew Tonkovich

The door of my office at UC Irvine was once covered in peace and justice bumper stickers, a modest provocation or unsubtle encouragement to embrace civic engagement, not to mention a way to identify the otherwise hard to find redoubt of an underpaid, undervalued adjunct Composition instructor and union activist at the end of a long hall in a building far from my classroom. My favorite sticker was the ironic if also simultaneously sincerely encouraging “Oh, no, not another learning experience!” Yes, it was funny and self-deprecating but joking about the responsibility of learning, and celebrating, assuming, and insisting that learning is a requirement, an experiment, a struggle, generally got a laugh and acknowledged our shared struggles as a community of learners.

There’s a punchline. The University sent a letter informing me that the stickers caused damage to the door and instructed (sic) me to remove them. Now there’s a learning experience.

This issue of our invitation-only in-house journal demands your attention and engagement. It’s a learning experience, for sure, and perhaps with some tough, if necessary, beautiful, even redemptive lessons.

Courage, tenacity, and stubborn commitments written about, lived, created, and realized show up in a staff member’s craft talk — “a poem might be described as the tension between the said and the unsaid“ — a newspaper commentary, a cri de coeur meets editorial manifesto, origin stories, and new poetry and nonfiction work from or about recently published and even award-winning alumni work. Thoughtful and self-aware, sincere, and empathetic, the writing here resonates with commitment, gravitas, and steady joy.

Oh, yes, please! More learning experiences! About writing, struggle, creativity, and engagement!

Andrew Tonkovich

Editor, OGQ

THE POETIC LINE BREAK

The Ear, The Eye, and the Drama of Silence

By Victoria Chang

“A sentence has any number of possibilities for grace, tension, seduction, force—the line is the poet’s opportunity to send an extra ripple through all of these.”[1]

—Carl Phillips

My friend, the poet Matthew Zapruder and I were talking about this talk and he that breaks lines by “intuition,” to which I replied: “What is intuition but knowledge set free?”

Charles Wright prefers the “making” of a line versus “breaking.” James Longenbach prefers “line ending.” Catherine Barnett takes a feminist view, preferring “break” because she says that she spends “an awful lot of time trying to fix things, trying to make things. I am glad to be able to break,” she says. She then says that line breaks are also a chance to “keep beginning.” Lately, I’ve been thinking about the line break in the context of music and visual art. And so this is how I will enter the world of line breaks, by wandering in sideways.

The Musical Rest

I grew up playing piano and the moon guitar which is a Chinese instrument shaped like a full moon. My mother sang Chinese opera and so my ear was used to the clanging of the gong, the high pitched sounds of the er hu. A Chinese Opera friend of the family from China taught me how to play the moon guitar. For the piano, I had a completely different experience. I took lessons from an older Chinese American woman whose family was many generations in America. I took lessons for 10 years, and was mediocre, but I managed to learn how to read music.

Music obviously consists of musical notes. But musical composition, along with reading and playing music consist of another essential element: silence. In a musical score, silence is called a rest. It’s notated like musical notes, and therefore, in some ways, silence is its own note too. When no music is playing, ambient sounds fill that space (your own breathing, the thoughts in your mind, the rain drops dripping out of the gutter, the laundry machine, the buzzing of the light bulb, what music came before the silence, as well as the anticipation of what music will come next).

We often think about a poem as the letters and words on a page, the actual utterance, but I tend to think that what makes a poem a poem is what’s not on the page, the silence, what might be implied or even unknown, the unsayable, the unsaid. The relief of language.

The words and lines are both an utterance on the page and a withholding of breath, an interaction with silence. Similar to music, in a poem, silence is a word too, a correspondence with words, all the words before, and all the unwritten ones after. In that way, a poem might be described as the tension between the said and the unsaid. The sayable and the unsayable.

In poetry, that silence is most easily accomplished by leaving explicit things, images, or ideas out of the poem. Poetry also operates within the figurative realm so the lacunae between the tenor and the vehicle of a metaphor is another kind of silence or gap. Another way a poem mediates silence is through caesuras which are breaks or pauses within a line (often represented by a physical gap, commas, periods, dashes, and colons).

There are eight types of rests in music. If you think about the music you listen to, rests are physical notations of those moments when certain instruments (including the voice) are not playing anything at all. In music, like in poetry, silence is not equal or arbitrary.

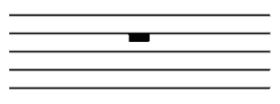

The whole note rest looks like this:

It’s called a “semibreve” rest, lasting the length of a whole note or the value of four beats. It’s a small rectangle that hangs off the second line from the top of the staff or stave (the five lines the notes are written on).

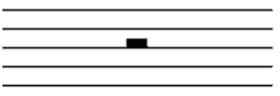

The half note rest looks like this and is called a “minim” rest. It’s a small rectangle very similar to the whole note rest but instead of hanging from the second line, it sits on the middle line of the stave. It has the value of two beats.

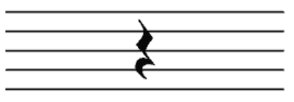

The quarter note rest is a fancy looking symbol called a “crotchet” rest, and covers the duration of a quarter note. This rest has the value of one beat.

There’s also the eighth note rest, or the “quaver” rest, which has the value of half of a beat, the same as a quaver note. I love the word “quaver” which also means to tremble.

Then there’s the sixteenth note rest, the thirty-second note rest, dotted rests (which is one and a half times the length of an undotted rest—so a dotted quarter rest would last as long as one and a half quarter rests), rests with a fermata (this means the exact length of the rest is up to your discretion).

It may be useful to think about line breaks with musical rests in mind because of how the variations in musical rests might resemble varying line breaks in poetry. What’s the difference in pause between a noun versus a verb? An article or a noun? A period or a comma? An em-dash or a colon? A colon or a semicolon? I actually think musical rests can be a useful way to think about caesuras in poetry too. What’s the difference in pause between an empty space that’s one centimeter versus four centimeters?

_________________________________

[1] Carl Phillips, “Some of What’s in a Line,” from A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line, edited by Emily Rosko and Anton Vander Zee, University of Iowa Press, 2011, p. 187.

Visual Art and Saccades

My sister was an excellent percussionist and marimba player. While I also learned how to play the drums and marimba, I preferred the pencil versus the drumstick, mallet, or fingers for piano. I spent most of my time drawing and writing.

Even though I don’t really play much music anymore, I have such fond memories of learning how to play the moon guitar with Uncle Li and of playing piano, the snare drum, and the marimba.

I don’t draw much anymore either, doodle a bit here and there. But every chance I get, I will go to an art museum or a gallery to wander around, often quietly in empty spaces large and small. I inevitably connect visual art, the art of perception and seeing, to the act of reading a poem or even writing a poem. In fact, I often think of writing a poem not as writing, but as making a poem, in the same way, one might make a painting. Because I learned music, art, and poetry all together, it’s hard for me to separate the three.

This might be more of a stretch than with music, but I think that line breaks in poetry might also be similar to the composition of a painting, for example, in how the artist, through certain visual choices, affects our seeing, the movements of our seeing, and the pacing of our seeing.

Joan Mitchell was known as an abstract expressionist whose work spanned four decades from the 1950s to the 1990s. Mitchell painted a piece called “To the Harbormaster (1957)” that was inspired by the poetry of Frank O’Hara. Small factoid, Mitchell’s mother, Marion Strobel, was an associate editor at Poetry magazine.

If we look closely at “To the Harbormaster,” we might initially think of a kind of unfettered chaos. But I think there’s organization and intention in this painting, and that intention shapes the way and the velocity of our seeing. It doesn’t matter where one’s eye might start looking—upper left, upper right, lower right, left, center; our seeing is paced by Mitchell’s compositional choices. My own eye is drawn to the largest blue shape at the left-middle—lingering there for a bit as it might hover on a word, line, or stanza, as this color shape is larger and wider. Sometimes I’ll immediately see the orange in the upper left or the reddish orange in the upper right. Other times, my looking will reverse and I’ll see the whiteish brushstrokes. Every time I look at this painting, just like a poem, I see something different and differently.

I think that the whiteish paint strokes in between the moments of color, play a role in how my eye moves. These white gestures act as visual breaks to the calligraphic color strokes and drips. I wouldn’t go so far as to call them moments of silence or emptiness, but they are to me at least, moments of transition, full of their own visual bustle. A different kind of viewer or on a different day, I might see the white paint as primary and the colors as moments of silence. Artist Franz Kline who was known for his sweeping calligraphy-like black paintings said: “I paint the white as well as the black, and the white is just as important.”

As I began thinking about seeing and its relation to line breaks in a poem, I thought about “saccades” and the movement of the eye while viewing something like a painting. This process of seeing is very complex. A saccade is a “rapid, conjugate, eye movement that shifts the center of gaze from one part of the visual field to another.”[2] When we view a painting, our eyes move in a series of quick simultaneous movements, or saccadic movements, and travel between phases of fixation on something in the painting. The way we see isn’t singular or in a vacuum, rather, they build up toward a “three-dimensional mental map” of whatever it is we’re looking at. This description of saccades reminded me of reading poems.

In another one of Mitchell’s paintings, “Ode to Joy,” the varying blocks and strips of color feel like poetic texts to me, because of the way the painting is composed. The painting encourages the eyes to make saccadic movements. The blocks and strips of a color’s size, shape, and brushstrokes, feel like a dynamic and lively poem, with moments of transition, articulated by whiter or lighter paint. To me, these moments of transition are not all that different from line breaks or musical rests.

In another one of Mitchell’s paintings, “Ode to Joy,” the varying blocks and strips of color feel like poetic texts to me, because of the way the painting is composed. The painting encourages the eyes to make saccadic movements. The blocks and strips of a color’s size, shape, and brushstrokes, feel like a dynamic and lively poem, with moments of transition, articulated by whiter or lighter paint. To me, these moments of transition are not all that different from line breaks or musical rests.

With some of Mitchell’s paintings, like “Ode to Joy,” there’s an added artificial rest which is the canvas. Mitchell’s studio in France was small, so she painted on different canvases and attached them together. These canvases feel a bit like stanzas in a poem—the horizontal triptych of canvases complicate the vertical pull of the brushstrokes.

Maybe thinking about music and art might help us think about line breaks within poems, perhaps as being more varying (as in the multiplicity of rests in music) or perhaps more dynamic (as in the lyrical and calligraphic poetic strokes of color and whites in Mitchell’s paintings).

_________________________________

[2] Wikipedia.

Private Utterance & Public Utterance

On the most basic and obvious level, line breaks are where the line in poetry is severed and the beginning of a new line is about to begin below it. But why do poets incorporate the line break into poetry? The line break is one of the main distinguishing features that differentiates a poem from prose. What makes a poem a poem is that it is often written in sentences (or fragments) and lines, allowing it to be read in multiple ways. As an example, here’s the beginning of a poem called “Trash” which is in Joshua Bennett’s book, The Study of Human Life:

I

All the men I loved were dead

-beats by birthright or so the legend

went. The ledger said three

out of every four of us were

destined for a cell or lead

shells flitting like comets

through our heads. As a boy,

my mother made me write

& sign contracts to express

the worthlessness of a man’s

word. Just like your father,

she said, whenever I would lie,…

The first line, “All the men I loved were dead” is its own line and its own unit of thought and music. The second line is also its own unit: “-beats by birthright or so the legend…” There are double meanings here, or syntactic doubling. The men in the speaker’s lives were both being killed or died, and also were deadbeats by rumor and “legend.” This syntactic doubling mirrors the complex subject matter, leaving the reader with a sense that there’s more than one frame in the story.

The third line feels sonically and rhythmically interesting to me: “went. The ledger said three.” The period right after the first word, plus its hard accent makes “went” very accented. Then things start anew with: “The ledger.” Because of how the line breaks change the syntax of the line, it feels like the ledger both walks and speaks. This line, isolated by itself, is a dynamic line of poetry.

But each line in a poem is also a part of a larger syntactical unit, and can span multiple lines. The first stanza and one word, “went” make up a sentence: “All the men I loved were deadbeats by birthright or so the legend went.” The third line, “went. The ledger said three” participates in three possibilities: its own line as a unit of thought, syntax, and sound, and two other sentences (the one that ends at “went” and the one that begins with “The ledger” and ends at “our heads”). So that sentence spans three stanzas and reads: “The ledger said three out of every four of us were destined for a cell or lead shells flitting like comets through our heads.”

I think it may have been Marianne Boruch who called the line a “private utterance” and the sentence a “public utterance.” While I think this is interesting, I think of the line verses the sentence as different ways of seeing. A sentence is a more conventional way of viewing, while a line, depending on its unique qualities is just a different way of viewing the same thing. Maybe a sentence can be likened to a branch of a tree, and a line, a sub-branch of a tree.

I’ll also mention the horizontal and vertical aspects of the poetic line—how a line tugs the reader horizontally, while a sentence simultaneously pulls the reader downward vertically. Seeing a poem as a physical whole of stretching right, and dropping is also perhaps how I think about paintings or other objects. Heather McHugh said something similar: “The line is where the wish to go forth in words (along one axis of a journey) encounters the need to break off—or fall out—with words (along the other axis, a vertical).”[3]

The obvious question one might ask is, why do poems have line breaks at all? With formal poetry and/or through the spoken tradition of poems, the line break was determined by form, the metrical grid, usually iambic pentameter. Since most contemporary poetry is no longer tied to traditional forms, the poet thus gets to make line break choices. So the assumption in this talk is that we’re mainly focused on free verse poetry, which is what most contemporary poets are writing. Raza Ali Hasan calls free verse a “broken thing”: “What we gain from this broken thing is our ability to overload the line, and, if need be, go almost to the right margin. What we lose is the peace of mind, the assurance that we know what we are doing—but that might just have been illusion in the first place.”[4] In “On the Function of the Line,” Denise Levertov argues that free verse is a more “open” and “exploratory” form that is more suited to our modern times.[5]

The most obvious and basic reason for breaking a line at a certain point is that each choice of where to break a line changes the fundamental nature of that line in terms of the display of thought. George Oppen says: “The meaning of a poem is in the cadences and the shape of the lines and the pulse of the thought which is given by those lines. The meaning of many lines will be changed—one’s understanding of the lines will be altered—if one changes the line-ending. It’s not just the line-ending as punctuation but as separating the connections of the progression of thought in such a way that understanding of the line would be changed if one altered the line division. And I don’t mean just a substitute for the comma; I mean with which phrase the word is most intimately connected.”[6] Levertov describes a line break similarly: “[a line break] can record the slight (but meaningful) hesitations between word and word that are characteristic of the mind’s dance among perceptions but which are not noted by grammatical punctuation.”[7]

Another common and related reason for line breaks is to set the pacing of a poem or to orchestrate disclosure. Carl Phillips describes pacing in a Frank Bidart poem: “The lineation controls the speed with which we receive information, and at the same time it isolates each piece of information, throwing it into greater relief.”[8] Oppen says: “The line sense, the line breaks, and the syntax are intended to control the order of disclosure upon which the poem depends.”[9] Oppen suggests that how a poem discloses information is what makes a poem a poem. I find that word “depends” to be a very assertive word. For Oppen, a poem depends on the order of disclosure.

Going a little deeper, and to keep quoting from Oppen, he says: “The line-break is just as much a part of language as a period, comma, or parenthesis, and it shows that there are things that can only be said as poetry.”[10] Here, Oppen suggests that the line break helps a poem do what only a poem can do. When I think about Oppen’s poems, I think this sums up his poetics because I think about Oppen as a poet of hiddenness, withholding, and pacing. His poems are very dependent on disclosure or lack of disclosure, with the line break as being one of his main batons. Lack of disclosure is perhaps just another way of saying silence.

_________________________________

[3] Heather McHugh, “Tiny Étude on the Poetic Line,” in A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line, edited by Emily Rosko and Anton Vander Zee, Iowa University Press, 2011, p. 164.

[4] Raza Ali Hasan, “The Uncompressing of the Line,” in A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line, edited by Emily Rosko and Anton Vander Zee, Iowa University Press, 2011, p. 120.

[5] Denise Levertov, “On the Function of the Line,” page. 30.

[6] Ibid, 314. Selected Letters, 167.

[7] Denise Levertov, “On the Function of the Line,” page. 31.

[8] Carl Phillips, “Some of What’s in a Line,” from A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line, edited by Emily Rosko and Anton Vander Zee, University of Iowa Press, 2011, p. 188.

[9] Ibid, 314. Also, Selected Letters, 141.

The Art of the Poetic Line

The late poet and critic, James Longenbach, wrote extensively about the line in his book, The Art of the Poetic Line (2008). He focuses on the relationship between syntax and line. He writes: “The fluctuating tension between syntax and line is itself in tension with the thematic content of the speech, and there is no predictable relationship between the form and the content. In other words, the passage does not simply describe a movement of thought; it embodies and complicates that movement through the relationship of syntax and line. This is what great poems do.”[11]

In The Art of the Poetic Line, Longenbach suggests thinking of lines as either end-stopped or enjambed, with end-stopped lines usually indicated by a period, but also can be indicated by an exclamation point, question mark, colon, semicolon, or possibly even a comma. Each of these end-stopped lines is not created equal, with a period being the most final type of end-stopped line. In terms of the length of a pause, it’s hard to say whether a period or a question mark or a colon or semicolon or even a comma might engender a longer pause. I think it’s easiest to say a period might have the longest rest, but I’m not so sure without the line itself and the context of the line.

According to Longenbach, we can subdivide enjambed line breaks into another two categories, parsed or annotated, which I’ll explain in a second. Incidentally, the word “enjambment” is from the French word “enjamber” which means “to stride over, to encroach” and is derived of “jambe” which means leg, so enjamb can mean “to put a leg across,” or “to straddle or encroach.” Enjambment simply means breaking a sentence or fragment from one line to the next.

Longenbach is very clear that these divisions are for definition purposes because the power of free verse “most often depends on the interplay of these different kinds of line endings,”[12] which is basically saying that everything is interrelated. I think of poetry this way too—it’s a series of relationships, sometimes of which certain elements are working in concert with each other as a canoe might drift down a river, and other times, against each other as a fallen tree trunk that cuts across a part of a river, that makes the water flow differently. I’ve also described a poem like a grandfather’s clock, with all the little pendulums, lures, weights, and cables working together and against each other at different times.

According to Longenbach, parsed line endings are lines that are enjambed, but they “break at predictable points rather than cutting against” the syntax.[13] The parsing line “tends to emphasize the given contour of a sentence, reinforcing the way it would sound if it were written out as prose.”[14] Parsed is a bit of a funny word because it means to examine or analyze, or to analyze a sentence by its parts. I think of this kind of enjambment as “natural,” following the natural rhythms of speech and sentence, where one might naturally pause, at a comma, complete phrase, or clause, of course qualifying to say that what’s natural for one person isn’t natural for another person. Poets such as Wallace Stevens and H.D. used the parsing line more often than not, according to Longenbach. He added: “…by serving up a poem’s syntax in clearly apprehendable units, the parsing line may allow us to inhabit a syntactically complex argument more viscerally.”[15]

Here’s an example that Longenbach provides, from “Pastoral” by William Carlos Williams:

And no one knows

Whether we think good

Or evil.

These things

Astonish me beyond words!

I also tried parsing lines with Rilke’s “First Elegy” (translated by Edward Snow):

Who, if I cried out,

would hear me

among the angelic orders?

And even if one of them

pressed me suddenly

to his heart:

I’d be consumed

in his stronger existence.

For beauty is nothing

but the beginning of terror,

which we can just barely endure,

and we stand in awe of it

as it coolly disdains to destroy us.

Every angel is terrifying.

I’ve butchered Rilke’s first elegy, but I think this is a good example of how a parsed enjambed line might look (obviously there are more ways to parse the same lines than what I did here). I parsed Rilke’s line according to more singular units. We’ll go back to Rilke’s original version in a second.

James Wright’s “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota” is a poem that is mostly end-stopped. But in the two cases where the lines are enjambed, they are parsed, where the lines could be said to lineate naturally by phrase. Wright’s free verse is syntactically natural, complete, and unified.

Over my head, I see the bronze butterfly,

Asleep on the black trunk,

Blowing like a leaf in green shadow.

Down the ravine behind the empty house,

The cowbells follow one another (enjambment: parsed, complete sentence)

Into the distances of the afternoon.

To my right,

In a field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year’s horses (enjambment: parsed fragment)

Blaze up into golden stones.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk flies over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

The lines in the poem mimic the tone of the speaker who is contemplative. The line breaks flow and blow like a gentle wind might—naturally, smoothly, quietly, but not uniformly, given the different line lengths. The speaker is looking around at the world and suddenly realizing that he has never looked before. But the realization is both jarring and natural. This puncturing calm is evoked by the gentle mostly end-stopped line breaks.

Imagine a different kind of more heavily enjambed line:

Over my head, I see

the bronze butterfly, asleep on

the black trunk, blowing like a

leaf in

green shadow…

This feels very different, which brings me to the annotated enjambment. These are lines that are enjambed but “rather than following the grammatical units, the lines cut against them, annotating the syntax with emphasis that the syntax itself would not otherwise provide.”[16] An annotating line increases the tension between syntax and line as it proceeds. In this example, the annotated enjambed lines create more tension, urgency, and evoke a tone of regret.

In addition, the “more aggressive annotating line asks us to stress syllables we wouldn’t ordinarily stress.”[17] The example Longenbach uses is from Williams’s book, Spring and All and here’s just a little bit: [Can someone read this]?

The sunlight in a

yellow plaque upon the

varnished floor

is full of a song

inflated to

fifty pounds pressure

at the faucet of

June that rings

the triangle of the air

pulling at the

anemones in

Persephone’s cow pasture—…

Longenbach writes: “Williams bends his syntax relentlessly across the line, and the line endings generally do not perform the work of punctuation or emphasize the turns of normative syntax…Williams uses enjambment to determine the placement of rhythmic stress, playing the irregularity of his line endings against the chaste decorum of his three-line stanzas.”

Similarly, my friend, the poet, Rick Barot, categorizes enjambments by what he calls “function words” versus “content words.” Function words are often prepositions such as a few of the bolded words in the poem, and are harsher and more radical; they undercut sentiment. Softer content words are those such as “pressure” or “pasture.”

Longenbach goes on to talk about how sometimes Williams’s enjambments throw emphasis on the beginning of the line and other times on the ending of the lines, depending on their construction. In the first stanza, the “a” at the end of the line is unstressed, thereby throwing extra emphasis on the word “yellow” in the next line, and the same is true with the word “the” and “varnished,” in the second and third lines. While in the second stanza, “song” is a stressed syllable so the next line of “inflated” is unstressed. I think what Longenbach is getting at here is that if you stretch out the line to sentences or even just longer lines, the same syllables would be stressed or unstressed, but the spikes of stressed rhythm would be flattened. The line breaks accentuate the beginning or ending of lines.

u / u / u

The sunlight in a

/ u / u / u

yellow plaque upon the

/ u /

varnished floor

u / u u /

is full of a song

u / u u

inflated to

/ u / /u

fifty pounds pressure

/ u / u /

at the faucet of

/ u /

June that rings

u / u u / u /

the triangle of the air

/ u / u

pulling at the

u / u / /

anemones in

u / u / / u u

Persephone’s cow pasture—…

As just one example, if we elongate Williams’s line and read it aloud, “The sunlight in a yellow plaque upon the varnished floor,” the rhythmic spikes of the line become a bit flatter. Without the line breaks of the original poem, the dramatic tension is released. Even with a parsed enjambed line, the emphasis on the ending of the lines and the beginning of the lines, while still there, is diminished when compared to a more drastic annotated enjambment of the original. Here’s an example of a parsed enjambed line:

The sunlight in a yellow plaque

upon the varnished floor

If we are to bring back the musical rest, it seems that end-stopped lines might be associated with the whole rest, as I said above, while enjambed parsed lines might be quarter or half rests, depending on where the enjambments are within the syntax of the sentence, what particular words are enjambed, etc. Finally, annotated enjambments might be quarter note rests or even shorter such as eighth note rests. I might annotate these Williams lines with different kinds of musical rests this way:

The sunlight in a (eighth rest, unstressed syllable)

yellow plaque upon the (eighth rest, unstressed syllable)

varnished floor (half rest due to the stanza break and due to the noun and stressed syllable)

is full of a song (quarter rest, noun, and stressed syllable)

inflated to (eighth rest unstressed syllable and preposition)

fifty pounds pressure (half rest due to the noun, unstressed syllable, and stanza break)

These are my best guesses, meaning, there aren’t any right answers. Read the lines aloud and see how long they ask the reader to rest. Basically again, many things work together and against each other to emphasize certain words, de-emphasize certain words, pace the poem more quickly or more slowly, etc. When I read the whole section aloud, it feels jagged, full of starts and stops. But the irregular rhythms match the increasing strangeness of the imagery while pressing against more regularities such as the iambs in the first stanza and the balanced tercets.

Longenbach warns us though, of the downfalls of each way of enjambing a line: “The excessive use of the annotating line can come to seem mannered or fussy, a way of jazzing up uninteresting syntax, just as the excessive use of the parsing line can come to feel dull, a way of merely repeating what the syntax is already doing on its own.”[18]

Going back to Rilke’s first elegy, we see that his lines are longer lines, with a fair number of parsed enjambed lines. I think the longer lines fit the subject matter well, which is like a cry outward, running out of breath (often exceeding 10 syllable lines which is the length of one breath), into the void. Here are the first few lines, where I’ve notated them as end-stopped or parsed or annotated, if enjambed, and also labeled them in the context of musical rests too.

Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic (annotated) (quarter note rest)

orders? And even if one of them pressed me (parsed) (half note rest)

suddenly to his heart: I’d be consumed (parsed) (half note rest)

in his stronger existence. For beauty is nothing (parsed) (half note rest)

but the beginning of terror, which we can just barely endure, (end-stopped) (whole rest)

and we stand in awe of it as it coolly disdains (parsed) (half note rest)

to destroy us. Every angel is terrifying. (end-stopped) (whole rest)

Each longer line feels like its own unit of crying out, out of breath, slightly extended beyond the typical length of a breath (iambic pentameter) to 14 (at least in translation) syllables of the first line, 11, 10, 13, 16, 12, 12, in the others. The poem is studded with caesuras in the middle of the lines. The poem’s line breaks are mostly enjambed and thus mirror the desperate feeling of the speaker. The poem is teaching the reader the pacing of the poem as we read it. Many of the lines are parsed, meaning they break at smaller units of syntax, as if the speaker is taking a breath, emoting outward, but needing to take a break in order to breathe.

Some of the parsed lines create multiple syntactical possibilities as thinking and feeling travel across lines. As an example, line three: “I’d be consumed” can stand on its own, but gets extended in meaning by “in his stronger existence” in the next line. The same is true for the fourth line: “For beauty is nothing/but the beginning of terror” which is gorgeous as “For beauty is nothing” and equally gorgeous as “For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror.”

Obviously, such enjambed parsed lines with their extensions complicate the lines in terms of meaning. But one might also argue that such longer parsed lines create a different kind of pacing, where there’s a longer pause at the line break, perhaps a half note rest, which is breath number two, then as the reader continues to the next line, there’s a backward movement at a caesura, before another forward propulsion. The second half of the sentence or phrase needs to find its antecedent. Basically, there’s clear rhythmic pacing and work being done here due to the caesuras in the line, the longer lines, the line endings, and the line breaks in relation to the syntax of the lines. The effect is a tone of jagged urgency and desperation.

Going back to my own enjambed parsed line breaks of Rilke’s poem, I might revise my self-criticism and say that it’s not a truly terrible version, but something is gained, while something is lost. There’s a little more kinetic energy within a shorter line, but because of all the eye-turning from line to line and the pauses after the line breaks, the pacing is arguably slower and more disrupted. Different words are emphasized at the end of these short lines, as well as at the beginning of the lines.

Because of the short lines, I might argue, that the accented syllables stand out more. If we look at the first three lines, because they are so short, “Who” is stressed, along with “cried” and “out” more strongly than if they were part of a longer line: “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angelic/orders…” where “Who” is still stressed, and we can hear the “hear” a little more strongly but all the other words that stood out with the shorter lines become a little more muted.

/ u u / /

Who, if I cried out,

u / u

would hear me

u / u u / u / u

among the angelic orders?

If we go back to the Rilke example again, I have enjambed these lines in an even more annotated fashion, cutting off syntax at key moments:

Who, if I cried

out, would hear

me among the

angelic orders?

And even if

one of them pressed

me suddenly to his

heart: I’d be

consumed in his stronger

existence. For beauty is

nothing but the

beginning of terror,

which we can just

barely endure, and we

stand in awe of it as it

coolly disdains to

destroy us. Every

angel is terrifying.

I feel as if I’ve once again destroyed our beloved Rilke. This speaker feels a little more manic, a little too manic, one that might have his hands tangled in his hair, muttering these words, pacing back and forth, in a dark castle, with the wind howling outside the window. The rhythms feel jerky. It’s not an awful version, but I still much prefer the longer lines of Rilke’s poem.

I want to quickly point to an example people often use when talking about line breaks which is “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks, to illustrate line breaks as a way of calibrating velocity and emphasis:

We Real Cool

The Pool Players.

Seven at the Golden Shovel.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

This is a shorter poem, but given the dramatic annotated enjambments with the “We” at the ends of the lines, one might argue that the pacing is slightly quickened as the eye whips from the end of a line to the next, maybe, while also being heavily emphasized. Here, the line break is a suspense device and also a device of emphasis. Or we can argue that dramatic line breaks slow things down. However, if we write out the lines without line breaks and read it aloud, this line without breaks feels faster:

We real cool. We left school. We lurk late. We strike straight…

Ultimately, I think it’s hard to tell. I think the jarring break after “We” creates a pause, maybe an eighth rest. Also note that all of these words are monosyllables, and also varying degrees of stressed syllables. There are a lot of things happening in this miniature poem. Incidentally, Gwendolyn Brooks reads her own poem with a short pause after each “we” and she reads each “we” softly.

_________________________________

[1o] “A Festschrift for Burton Hatlen,” p. 314 (need to get source).

[11] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 13.

[12] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 49.

[13] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 55.

[14] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 55.

[15] Longenbach, p. 68.

[16] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 53.

[17] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 55.

[18] James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line, p. 57.

Conclusion

We could, of course, analyze poems and their line breaks forever. There’s so much more I’d love to talk about, but I’m out of time and space, and breath. Ultimately, I think about poetry as patterning, and also thus of breaking of those patterns, and the tension created by the movements between and amongst those varying patterns.

Line breaks are also about patterning and the breaking of that patterning. In this way, line breaks are constantly in conversation with other line breaks. And obviously, line breaks are just one aspect of poetry, where numerous other things are happening all at once—a testament to our mind’s capacity to absorb and process all of these patterns simultaneously. Once I began to think about line breaks as musical rests or interstitial spaces of seeing in visual art, or as parsed or annotated syntax, I began to think of line breaks as the tension between all the senses at once—of speaking and silence, of seeing and absence.

Understanding the effects of line breaks can help the poet make end-of-the-line choices. Going back to musical rests, does the line break evoke a whole note rest, a half note, quarter, eighth or something else? Thinking about visual art, how do the line breaks slow down or speed up the eye? How do line breaks accumulate, in the way saccadic eye movements accumulate into a mental map, by the end of the poem? Using Longenbach’s frame, are the lines end-stopped or enjambed? If they’re enjambed, are they parsed or annotated? And how do line break choices change the emphasis on different words at the ending and beginning of lines?

Line breaks are like anything else. Once you notice them, you might never be able to un-notice them, as a poetry maker, breaker, ender, and maker of new beginnings. I’m a tryer. I always try my hardest, but I also love trying everything. My best advice about line breaks is my general approach to life—just start trying different ways to break, cut, interrupt, make a line and ask yourself what effects that particular kind of line break has on the poem—discoveries that the sentence and the poet might not have seen before the line break. There’s no “right” way to break a line, but once you start playing around, you’ll see all the different ways a line can exist within itself, within the poem as a whole, and within an entire era of our lives. Ultimately, a line is a smaller unit amongst other larger units of fragment, sentence, thought, poem, life, and world.

Be a rebel, like a line is a rebel to the sentence (I think Marianne Boruch said that too), and allow your lines and sentences to be free-er, stranger, and thus making new discoveries into the unknown, as the lines negotiate and renegotiate our thinking, seeing, and hearing. I’ll end with a few quotes, the first one a process one by Joanie Mackowski: “More productive line breaks develop in conversation with the poem taking shape on the page: as one observes the developing images and structures and bends with them to yield multiple resonances.”[19] I love the idea of a poem in process, in motion, and line breaks as part of that movement and act of discovery and multiplicity. In some ways, a line break activates the poem and the reader, engaging the participation of the reader.

Going back to music, musicians often describe silence in music as important loci of expressivity. I like to think of line breaks as important loci of a poem’s expressivity too. Once we reframe silence not as relief or absence, but a presence, and a presence in relation to everything before it and everything that hasn’t happened yet, silence becomes a note, as its own signifier, as a main part of a composition, a dramatic vehicle in a poem’s music and syntax, as an instrument not only to convey the particularities of our fraught times, but also to liberate us from the particularities of our fraught times.

I’ll end with a quote from Alice Fulton: “The blanks of poetry are its loudest moments. They are silence multiplied, shaking the bars of language [free]. And as we read, we become the space where lines [and our lives] fibrillate and multiply.”[20]

_________________________________

[19] Joanie Mackowski, “And Then a Plank in Reason, Broke,” in A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line, edited by Emily Rosko and Anton Vander Zee, Iowa University Press, 2011, p. 156.

[20] Alice Fulton, “As a Means, Shaped by Its Container,” from A Broken Thing: Poets on the Line, edited by Emily Rosko and Anton Vander Zee, University of Iowa Press, 2011, p. 96.

Victoria Chang’s forthcoming book of poems, With My Back to the World will be published in 2024 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Her latest book of poetry is The Trees Witness Everything (Copper Canyon Press, 2022). Her nonfiction book, Dear Memory (Milkweed Editions), was published in 2021. OBIT (Copper Canyon Press, 2020), her prior book of poems received the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in Poetry, and the PEN/Voelcker Award. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Chowdhury International Prize in Literature. She is the Bourne Chair in Poetry at Georgia Tech and Director of Poetry@Tech.

Victoria Chang’s forthcoming book of poems, With My Back to the World will be published in 2024 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Her latest book of poetry is The Trees Witness Everything (Copper Canyon Press, 2022). Her nonfiction book, Dear Memory (Milkweed Editions), was published in 2021. OBIT (Copper Canyon Press, 2020), her prior book of poems received the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in Poetry, and the PEN/Voelcker Award. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship and the Chowdhury International Prize in Literature. She is the Bourne Chair in Poetry at Georgia Tech and Director of Poetry@Tech.

NO BETTER REVEALER OF TRUTH

On Founding A New Journal, Frozen Sea

by William Ward Butler

Frozen Sea is a new online poetry journal with an emphasis on publishing exceptional work from early-career poets in a mobile-friendly format.

Frozen Sea is a new online poetry journal with an emphasis on publishing exceptional work from early-career poets in a mobile-friendly format.

Franz Kafka once wrote, “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.” Before he died, one of Kafka’s last wishes was to have his work burned. We’re only able to read Kafka because his friend, Max Brod, refused this instruction and thought his work was worth sharing with the world.

I started Frozen Sea in October 2023 with Jackson D. Moorman; we got to talking about the landscape of literary journals today and acknowledged that most of our friends primarily read work from journals on their phones—we wanted to create a reading experience that was formatted so as to be easily read on a phone’s screen.

There’s a few reasons for this. First, we want the work of our contributors to be shared as widely as possible, so we wanted to create a reading experience that made it simple for work to be shared widely: that’s why social media is such a big part of our strategy. As of this writing, we’ve received a little over 2,000 unique visitors to the Frozen Sea website and poems published in Frozen Sea have received nearly 20,000 combined views on Instagram Reels. Frozen Sea also maintains a presence on X, Bluesky, and TikTok. We’ve found that social media drives a majority of visitors to our website.

Additionally, we want the work we publish to be accessible. Frozen Sea is free to access, free to submit to, and we run audio recordings of all accepted poems so that readers can hear authors read their work. We also publish visual art, acknowledging that there’s not a hard division between poetry and art.

Jackson and I have seen many promising online journals suddenly disappear, along with all the work they’ve published. It’s sad when this happens—one strength about online publishing is that the internet is an archive, so the work that’s published can stay up in perpetuity. We make a sincere promise to our contributors to maintain our website and internet presence so that their work doesn’t go away.

Frozen Sea offers ongoing support of contributors through promotion on social media—we like to celebrate the achievements of our contributors and keep in touch! We’re building a community—Frozen Sea is beginning to feel like our own small slice of the internet, a meeting place where people can read and celebrate work from new and exciting authors.

Our focus is on publishing and promoting exceptional work from early-career poets. Submitting to journals and publishing can often be a demoralizing experience: as writers ourselves, we’ve experienced plenty of submission fees, slow response times, and journals that are print-only and limited in distribution or online-only and formatted poorly (or, disappear without a trace). Frozen Sea has no submission fee, we aim to reply within 30 days or less, we write personal rejections as often as we can, and we take our mission of elevating new voices seriously.

Jackson and I read submissions together and we have to agree unanimously to accept work in order to publish—we have to like it enough to want to format it for the website, format it for social media, and make an ongoing commitment to promote that contributor. Unless a piece gets a “no” from both of us, we tend to talk about the merits of the piece and how we see it fitting in with Frozen Sea. We’ve received a lot of incredible work so far; when we send a rejection, it’s all about fit rather than any determination on whether the piece is objectively good or not. We encourage all submitters to send work for future issues of Frozen Sea if they’re rejected at first—so far, we’ve accepted multiple contributors who’ve previously had at least one submission rejected.

We have a commitment to the contributors we publish to be a good home for their work, and we have an emphasis on publishing work from queer writers—we’re both queer ourselves, and find that queer voices are often marginalized in publishing in different ways. We hope to be a journal that is known for championing work by queer writers and under-represented voices.

In terms of our values, we aspire to, and work towards anti-imperialism, anti-capitalism, anti-fascism, anti-racism, anti-misogyny, anti-transphobia, and anti-homophobia through publishing and in our personal lives. As my co-editor-in-chief Jackson D. Moorman writes, “Poetry is not apolitical. Art is meaningless without a commitment to human dignity and autonomy; poetry is meaningless when stripped of its ability to interrogate the world as it is and its capacity to dream of a better one.”

We’re committed to using our platform as much as we can in order to speak on social issues. In 1963, James Baldwin opened “A Talk to Teachers” by saying, “Let’s begin by saying that we are living through a very dangerous time.” That’s still true—we live in a world with rising fascism, accelerating violence, and state-sponsored genocide. Poetry is political because truth is political, and there is no better revealer of truth than poetry.

We’ve received submissions and support on social media because of our clear statements speaking out against Israel’s ongoing genocide of Palestinians with the vigorous support of the United States. We’ve expressed solidarity with editorial staff who have resigned from positions in literary organizations that have failed to meet the moment and unequivocally condemn genocide. Anne Boyer’s resignation letter from her position as New York Times poetry editor speaks volumes: “I can’t write about poetry amidst the ‘reasonable’ tones of those who aim to acclimatize us to this unreasonable suffering. No more ghoulish euphemisms. No more verbally sanitized hellscapes. No more warmongering lies. If this resignation leaves a hole in the news the size of poetry, then that is the true shape of the present.”

Frozen Sea publishes Issue Three on February 15, and has committed to a quarterly publication schedule of four issues per year. It’s been wildly fun to make Frozen Sea so far—I feel that I’ve gotten to know my co-editor-in-chief Jackson as a friend and as a collaborator on the journal, and we’ve been so excited to publish new and incredible writers; being on the publishing side of things has been rejuvenative to my own poetry, and I’m looking forward to putting together more issues of the journal in the future.

The literary landscape is always in need of new publishers—if you’ve ever considered joining a journal’s staff or creating your own journal, go for it. Now’s the time.

William Ward Butler is the poet laureate of Los Gatos, California. He is the author of the poetry chapbook Life History from Ghost City Press. He has received support from the Community of Writers and the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference. He is a poetry reader for TriQuarterly and the co-editor-in-chief of Frozen Sea: frozensea.org

William Ward Butler is the poet laureate of Los Gatos, California. He is the author of the poetry chapbook Life History from Ghost City Press. He has received support from the Community of Writers and the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference. He is a poetry reader for TriQuarterly and the co-editor-in-chief of Frozen Sea: frozensea.org

THE STORY BEHIND THE STORY

by Amanda Churchill

The day before my Japanese grandmother’s death in March of 2014, we watched sumo. When I walked in, my father was perched in the corner chair, my grandmother small in her bed. The basho was turned up loud and I know that the other residents in the assisted living community probably wondered what was happening inside my grandmother’s room. Between the grunts of the wrestlers was the applause, the announcers and then the drumming.

The day before my Japanese grandmother’s death in March of 2014, we watched sumo. When I walked in, my father was perched in the corner chair, my grandmother small in her bed. The basho was turned up loud and I know that the other residents in the assisted living community probably wondered what was happening inside my grandmother’s room. Between the grunts of the wrestlers was the applause, the announcers and then the drumming.

I kissed her forehead and her eyes fluttered. This was her fourth time in hospice care. Each time the nurses had declared it the end, she had miraculously come back around, sitting up in bed, demanding breakfast or, sometimes, a cigarette.

I was hopeful this time would be the same. That she was just playing us again.

But the room felt strange, electrified. I thought it was maybe the sumo, the whisper of the salt the wrestlers were tossing to ward off evil spirits. A buzz from the television’s speakers, maybe. My father had been there all night and he looked tired. He joined me at her bedside and gently swabbed Grandmommy’s mouth with a damp cloth, put Carmex on her lips. He ran his fingers through her hair.

“Look at her, Mandy, look at all that hair. Look at her skin. She doesn’t really look like she’s dying, does she?”

She didn’t. Her skin was still taut, oily even, nothing was sunken in her face, her jaw was set firm and she simply appeared to be dreaming. But, it was strange for me to be touching her like this, running my hands along her face and hair. Had she been not dying, she would have slapped our hands away.

The television exploded in applause. My dad explained that the crowd favorite was 39-years-old, ancient in the sumo world, and he was about to win again. I watched as the man waddled into the ring, a white rope looped around his expansive waist. He turned his back to the camera and I saw his muscular butt and his diaper thong.

I asked where the match was being held and my dad finally smiled. Osaka. Of course.

***

I had often asked my grandmother about her village outside of Osaka as a teen, wanting to know where we came from, but she had waved me off like I was a pigeon in her way. It was the best place, she’d say. Very pretty. Go play with your cousins.

I was past playing age by then and in that strange land between childhood and adulthood, giggling one moment and crying the next, saddened by everything, delighted by just as much. My grandmother was not one for emotions and I was basically a ticking time bomb of feelings. As a parent of a young teen now, I fully forgive her forcefulness. Sometimes you just can’t.

But cancer softened her slightly and by the time I was pregnant with my first child, Grandmommy was willing to talk about the before. Before Texas. Before my grandfather, an American soldier who was complicated with demons, an abusive man who died before I knew him. Before the war. So I sat in her sunny living room, asking her questions. My father was sometimes with me, able to pull information out of her. She’d talk for a while about her sister and her brothers, the one she called “Pharmacy” because he always claimed to be ill with something, the one who teased her mercilessly and, finally when she couldn’t stand it, whose hand she had grabbed so hard she’d broken his thumb.

On accident? I asked.

She sputtered.

Oftentimes, she’d suddenly put her hand up, demand a snack and flip on the television. Like an interview with a reclusive movie star, our conversion was over. Full stop.

But once, just once, she spoke of a boy. He was a family friend, a boy with glasses. He was shy, smart, but scared of so many things. He thought she was brave and quirky. She thought he was sweet and gentle. He was not exactly from her village, but nearby. When she put on a play using the neighborhood kids as actors, he came and helped with the costumes.

They were engaged. Then he was drafted into the war.

I inched physically closer and closer to her in the room as she told this story, moving from one end of the couch to the other, then to the floor, then to the edge of her chair. She stuck one of her feet on my lap and kicked my pen that I was using to take notes.

I inched physically closer and closer to her in the room as she told this story, moving from one end of the couch to the other, then to the floor, then to the edge of her chair. She stuck one of her feet on my lap and kicked my pen that I was using to take notes.

“No ma’am. You tell me what happened, Grandmommy!”

My grandmother closed her eyes. She shrugged.

“Mandy, that’s all.”

***

At home I quizzed my mother and my father, did y’all know about this? They both did, but not any of the details. I asked my aunt. She had seen her mother crying once (only once… Grandmommy was not a crier) and it was because she had a dream about the boy. That he was on one side of a river, and her the other. He told her to go on, that he couldn’t cross and neither could she. It was impossible.

***

It seems funny to me now, but we let it go. Growing a family was keeping me busy, a perpetual motion machine of activity. I kept the notebook with my grandmother’s memories in a safe. My daughter was born. My grandmother healed and then became sick again. She could no longer be on her own in her home and the constant caregiving was exhausting my aunt and father. My grandmother was moved to an assisted living just four miles from my house. My son was born. I brought the baby to her and she smiled, touched his ears, his nose.

“Look like your daddy,” she said. She inspected his head where there was a double cowlick. “Uh-oh. Busy, this one.”

***

My grandmother died the evening after the sumo wrestler won his big match. I had just nursed the baby-who-would-be-busy and had put him back in his crib. My father called. I knew immediately what had happened.

“Just about thirty minutes ago. I’m with her now. Don’t come up. We’re waiting for the coroner. She loved you.” He hung up and my phone rang again immediately. This time it was my mother, from the hallway of the assisted living. I could imagine this scene. My aunt June and dad in the room, my uncle Bill and my mom merely feet away outside.

“Oh, honey, I just have to tell you something. She asked for a photo to be cremated with her before she died. Maybe a month or so ago. Daddy didn’t think much of it. She told him where the photo was and he thought it was of the family.”

I heard my uncle Bill whistle and say something like, “Tell her.”

“We found it and it’s the boy. The boy she was engaged to. How do I take a photo with this phone, Mandy? I’ll send it to you. Can you believe it?”

The photo showed up on the screen in my hand a second later. It was sepia-toned, a young Japanese soldier stood in the center. He wore wire-rimmed glasses and a plumed hat sat next to him on a stool. A banner in Japanese was behind his head. His bottom half was blurry, like he had been moving when the image was taken, almost like he was trying to leave.

***

The funeral was graveside and small. Her ashes were interred in the Gann family plot, next to my grandfather. Those on the outside of the family said how fitting it was that she could be with her husband again. Those of us on the inside said nothing.

I imagined it, her bones were mixed with a burned photo of this boy, laying next to my grandfather. Of course she knew it would be like this. I had to smile.

***

My debut novel, The Turtle House, features a grandmother very much like my own. A grandfather who is distant at best, abusive at worst. There is a granddaughter, begging to know more. There are an aunt and a father, Americanized, accidentally separated from their mother, not by geography, but by memory and culture. And there is a lost love. The one never forgotten.

I started writing it after my grandmother passed away. I was sleepless, hormonal, waiting for a baby to wake up and cry to be fed. A few times I could smell her as I wrote. Cigarettes. Coffee. And an umami scent that permeated every inch of her kitchen. She was there.

***

One afternoon during those interviews, on a rainy day and when I was good-and-pregnant, my belly now so far out I couldn’t see my tennis shoes, my grandmother had yelled out to me after I left her house. I was already down the steps, my hair getting wet. I climbed back up onto the porch and opened the storm door.

“What, Grandmommy?” I thought she needed something. Maybe she wanted me to reheat her tea, get her a blanket. She was in her recliner and her cat was on her lap. When I think of her in her older years, this is how I picture her, resting after a long, hard existence. A bowl of snacks nearby, the Japanese satellite beaming down life in her own language. She grinned at me and pointed her finger, wagged it a little.

You know, my stories. They make real good book one day.

Amanda Churchill is a writer living in Texas. Her work has been featured in Hobart Pulp, Witness, River Styx, and other outlets. She was a Writer’s League of Texas 2021 Fellow and holds a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of North Texas. The Turtle House is her first novel.

Amanda Churchill is a writer living in Texas. Her work has been featured in Hobart Pulp, Witness, River Styx, and other outlets. She was a Writer’s League of Texas 2021 Fellow and holds a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of North Texas. The Turtle House is her first novel.

EXCERPT

From The Resurrection Appearances: A Daybook

by Jay Aquinas Thompson

Below is a selection from a lyric memoir in progress, The Resurrection Appearances: a Daybook, a manuscript that began its life in workshops with Kazim Ali, Robert Hass, and Mónica de la Torre when I was a Gravendyk Memorial Scholar at the Community of Writers in 2018. Resurrection is an account of a grief year, told through narrative, lists, dreams, poetry, fantasy, and recollections of childhood, and beginning with the sudden death of my mom, Patty, in 2016. It’s a book of meaning-making, picking through the shambles after loss; it wouldn’t be the book it is today without the incitement and inspiration I found at the Community of Writers.

A chapbook-length selection from this manuscript was published by Gold Line Press in January 2024.

from The Resurrection Appearances: a Daybook

Winter evening in 8th grade, reading to her after she got home from work (this was the year she gigged as a carpet cleaner and fill-in special ed teacher) as she cooked pollo borracho: Douglas Coupland’s Life after God, austere Gen X fables of first-person pilgrims, all lonely and all somewhat interchangeable, seeking wholeness or homecoming out on the ragged edges of their lives. Nuclear-annihilation fable, divorced dad inventing fairy tales for his kid on a long drive into northern British Columbia, drug dealer lost in the California desert, one-time addict recounting his hotel year. The whole set of linked stories decorated with Coupland’s little doodles: a leaping salmon, a McDonald’s baked apple pie, a jammed-up sweltering overpass, a hand in silhouette. A little precious and a little lightweight, maybe, in retrospect—the characters’ ache isn’t news to anyone in our frantic, appetitive, young-souled culture, and their epiphanies don’t cut especially deep—but Life after God was the first account of spiritual fumbling and ardor I felt was mine. Why did we start reading them? Did I volunteer, was that right, to keep my mom company in the kitchen when she was too mad for NPR and too mentally staticky for music? I remember her pausing in coring a tomato and coming over to sit at the table and just listen. I finished the nuclear-war ghost story: “It’s like waking to find a demon sitting on your chest,” she said.

*

August 10: A dad reading to his daughter at the library in a dusty lilac fluorescent glow; the rooted self-sufficient glowing trees with their throbbing sheets of sap just under the bark; the buzz of a dog’s fur brushing my knees, the myopic persistence of my gut flora, the slow knotted-up ache of desire even in stone; nerves in my neck prickling; the runners, sporty and indomitable, passing each other without a smile down along the lake; and You, shining not vividly out from all of it but with a dim light, a damp heat, like a stir of the morning’s coals in winter or the half-shut eyes of a sleeping bear.

*

You’re resurrected in my frail aesthete’s bliss in a song—teenage Ella Fitzgerald singing “Betcha Nickel,” Johnny Guitar Watson striking out those first few notes of “I Want to Ta Ta You Baby,” Stan Getz’s soft exhaling sax solo on “Vivo Sonhando”—or the rum’s skinny legs or the frugal decent Trader Joe’s cheese specials I eat with an apple over the sink.

Resurrected in that hungry hurting latch-on shadow I’ll always carry, the child of your crying inside-child.

Resurrected in that tightening knot of fury I feel when the cops—they should be at home reading to their kids—move down the locked-in line blocking the street, tugging their bandanas down so the pepper spray gets a better shot.

Resurrected in my newborn sense of style, the same beaten-up thrifted antique hardwoods and flowering windowbox jasmine.

Resurrected in the sun-warmed syrup aromas of ponderosa pine when I get my nose close into the cracked bark.

*

I remember pinning this photorealistic poster of the Milky Way to my ceiling, falling up into it some nights when I’d slip into sleep.

I remember learning to come up with chit-chat to cover over the swear words in my music (Sublime, Public Enemy, Green Day, Cake with that one song whose chorus was shut the fuck! up! learn to buck! up!) when I would play it on my mom’s stereo. I remember talking over the murder threats that’d come up from time to time in the records (Lou Rawls crooning “C C Rider,” Aaron Neville singing “Over You,” Dylan croaking out “You’re Gonna Quit Me”—how many songs in the canon about guys promising to kill the women they loved?) she’d play over dinner.

I remember being alone in the world: holding on tight up on the high deck of a state ferry, first time through the San Juan Islands, ninety miles north of Seattle—I was seven—on our way to visit cousins. Washington’s ferries are big, companionable, noisy, and slow: inside were splitting plastic seats, smells of coffee and hot dogs and solvent, tourists, grownups playing cards by the big bay windows, radio personalities on the intercom paid by state government to cheerfully repeat safety bulletins. But whenever our family took a ferry, I’d always dash for the outdoor front deck, even on the short-run ferries hopping to and from downtown Seattle. My little body loved the wind strong enough to snap my windbreaker out behind me; seagulls riding our wind current; the shoe-sole throb of the big (diesel-foul I knew but mighty) engines through the metal deck floor; the rich wind-cut green-maroon surf splitting against us. This time, though, when I got to the deck half an hour out from the harbor on the mainland, I froze just past the big swinging doors. Outside, our boat was the only sign of civilization I could see in any direction. Nothing else but humanless islands, heaves of stone coated by clambering forests of madrone, hemlock, cedar, fir, all still from this distance as granite, receding into the secret colossal mutable shapes of water and sky that held them. Woozy with height and the rush of solitude, I squeezed the railing: would it be better if our boat never docked? Or if the captain (a mythical outline in a blue peacoat and cap) pulled us in to some deserted inlet and we splashed down to disembark, the adults all children again, scrubbed bare by the passage out of our reality into this one? Or if—I thought of looking behind me and refused myself—I was actually alone now on the boat, too, suddenly and definitively alone? First pilgrim, last child, heart knocking, living on hot dogs and Coke until it was time (I’d find a way) to dock my grumbling carriage and climb ashore and dance in admiration and obeisance to these wind-carved slow-pulsed madrones and cedars, to the bunched and tumbled and washed-out earthshapes—kames and kettles and wide mountains and messy moraines—left behind as the glaciers of the last Ice Age drew back? It had ended not so long ago: 10,000 years or so, I’d read it in a book, and it had all sat empty (the feeling was a tightening thrill all along my nerves) until the nobody-but-us arrived from our adult-world nowhere. Our little boat alone in the world: a world in its little hundred-century rest.

Jay Aquinas Thompson (they/he) is a poet, essayist, and teacher with recent or forthcoming work in Essay Daily, Adroit, and Poetry Northwest, where they’re a contributing editor. Their memoir The Resurrection Appearances: a Daybook is available now from Gold Line Press. They live with their child in Seattle, where they teach creative writing to public school students and incarcerated women. Substack: @jayaquinas, IG: @freshwater_merman

Jay Aquinas Thompson (they/he) is a poet, essayist, and teacher with recent or forthcoming work in Essay Daily, Adroit, and Poetry Northwest, where they’re a contributing editor. Their memoir The Resurrection Appearances: a Daybook is available now from Gold Line Press. They live with their child in Seattle, where they teach creative writing to public school students and incarcerated women. Substack: @jayaquinas, IG: @freshwater_merman

I was in college the first time I tried to write the story. The true story of my big brother and his friend. I’m not sure how they got the idea, what kind of drugs they were on, but in high school they came to believe they were the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, that God had chosen them for a special role in the End Times. I wrote about this episode in a course I took on memoir. My teenage self writing his memoir strikes me as funny now, but that was the idea. The trouble with my submission was, there was hardly any “I” in it.

I was in college the first time I tried to write the story. The true story of my big brother and his friend. I’m not sure how they got the idea, what kind of drugs they were on, but in high school they came to believe they were the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, that God had chosen them for a special role in the End Times. I wrote about this episode in a course I took on memoir. My teenage self writing his memoir strikes me as funny now, but that was the idea. The trouble with my submission was, there was hardly any “I” in it.

The story started with our parents’ divorce. For my brother the early years, with Mom at home still married to Dad, were an idyll, and he felt abandoned, shut out of his story-book childhood. He had a hard time making friends after we moved; I think a neighborhood kid actually spat on him. But it seemed to me he had a superpower in his laser focus. He would use it to create an impregnable force-field around him, shooting baskets at the Catholic school all day long. He got so good that for a time he became an all-American boy. A legend on his high school Varsity team, almost certainly headed for a scholarship to college. But he toppled from grace after breaking his arm and spiraled down from there. It must have been a lifeline for him, discovering himself in biblical prophecy. And Revelation’s fire and brimstone provided combustible fuel for his adolescent rage. The Antichrist would burn 666 into our foreheads. Torture us until we begged to die.

As for the “I” in my memoir, he got the hell out of there. Disappeared into school, where he became president of his class.

*

The second time I tried to write the story I was getting my MFA at UCI. In workshop we discussed where novels come from. The instructor told us hers had started with a single image. I can’t remember her prompt exactly, but in essence it was: don’t think too hard, just write a moment of resonance.

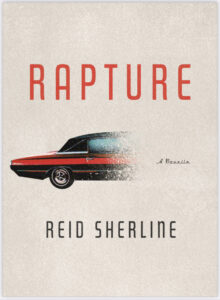

Writing exercises were difficult for me, but this one came easy. I wrote about a day in junior high. A Wednesday, two days before the Rapture would occur, according to my brother. He and his friend, and my little sister too, would all be taken, and I would be left behind.

All my life my brother and I had been locked in existential warfare, and I refused to cede him any ground. But I secretly prayed, at night in bed, that Wednesday walking home from school. I prayed for faith, in case my brother was right. I prayed not to be left behind.

I found our front door standing open, which did not happen in our house. My mother lived in terror of the Hillside Strangler, the serial killer terrorizing LA at the time. She believed she’d had a run-in with him in the dark parking garage at her work, and not even my brother wanted to see her scared like that again.

Inside the house, I called for my siblings but got no reply. I found the back door open too, the washing machine churning in the laundry room. I went from room to room, and there was a quality of interruption to each scene. The faucet running in my sister’s bathroom. My brother’s basketball slowly rolling in the yard. I heard the sound of distant sirens. In the book my brother had given me, The Late Great Planet Earth, that would be a tell-tale sign.

I knew the world would not end simply because my brother wanted it to, but it seemed my logic was no match for my fear, and by the time I found them, studying the Bible in my brother’s car, I was completely freaked out. I saw through the windshield my brother behind the steering wheel, his long hair a wild fringe beneath his sweaty Panama hat. My little sister in back, leaning forward between him and his friend, listening. We had been close growing up, and I started crying. My brother’s window was open, and I rushed it and yelled into his ear, “It’s not going to happen! God doesn’t give a shit about you.”

I left off there. The instructor asked if it was the start of something.

Rapture is Reid Sherline‘s first work of published fiction. He worked on the story in one form or another for many years, starting in undergraduate courses at Stanford, during his MFA at UC Irvine, and nights and weekends throughout a 25-year career in digital and educational publishing in New York and Philadelphia.

Rapture is Reid Sherline‘s first work of published fiction. He worked on the story in one form or another for many years, starting in undergraduate courses at Stanford, during his MFA at UC Irvine, and nights and weekends throughout a 25-year career in digital and educational publishing in New York and Philadelphia.

Bird Call Koan with Glossary

In memory of Dr. Ibrahim Farajajé

TOOLOOL, TOOLOOL

What if I were beautiful, what if I were enough?

TOOLOOL, TOOLOOL

What if I were beautiful, what if I were enough?

My child whispers that when the moon is a crescent, she can see the

shape of the whole outlined black against the blue-black sky. I tell

her there’s a side of the moon we never see. She lies in the dark

contemplating this, cycling her Fisher-Price lullabies over and over

into the night.

Across the hall I lie in the dark contemplating this, the infinitely

expanding universe of what I don’t know. Stars exploding and being

born. Moons in our own solar system still uncounted. And yet some

things I think I know with certainty: I’m not pretty. I don’t deserve

to be loved.

If I trill my mating call, who will answer me?

I forget the moon is always whole.

WHEEDELEE, KUEU KUEU KUEU

What if I were less than the fluff of milkweed, greater than the Milky Way?

WHEEDELEE, KUEU KUEU KUEU

What if I were less than the fluff of milkweed, greater than the Milky Way?

Ibrahim Baba, when you were in a coma I prayed this prayer: Don’t

let too much love and too much suffering burst your heart. But once

you tasted death, you couldn’t put it down. Too tempting to escape

the limitations of an ill-fitting body, the cruel politics of academia,

all the places a 6’5” Black Muslim tzitzit-wearing orange-bearded

pierced tattooed genderqueer father trying to save the world can’t

squeeze.

The basket you brought, once full of apples, still waits by the door.

When my father was dying you told me you were holding us in the

cave of your heart. I kept the voicemail as if to capture you in it like

a firefly in a jar. You were too much light.

Now that you can skate Saturn’s rings and vibrate the constellations,

can you hear your son’s Persian melodies on the tanbur without ears

to telescope eternity into song?

Can you recite Rumi where you are if Rumi is the object of a question

about desire to be made whole?

CHICKADEEDEE, CHICKADADEEDEEDEE

Is anyone looking, is anyone looking for me?

CHICKADEEDEE, CHICKADADEEDEEDEE

Is anyone looking, is anyone looking for me?

The map of my brain realigns itself, more water between islands

now.

I lie awake. I trust the boat. I trust the boat.

I trust the boat will come to take me back.

Experiment in drowning. Rest in cling. Drown again.

The half-moon reflects so brightly it knocks the stars out of the sky.

I feel I rose to see it, as if called.

Sometimes there’s a knowing and a nothing. A know and a no.

Do we love the moon any less when it’s not full?

CHIRUP CHIREEP CHIRUP

Hush, my babies, time to sleep

CHIRUP CHIREEP CHIRUP

Hush, my babies, time to sleep

נומי נומי ילדתי נומי נומי נים

Numi numi yaldati numi numi nim

Hush the lullabies, my chickadee.

Let me hold you.

Numi numi chemdati numi numi nim

נומי נומי חמדתי נומי נומי נים

You who taught me the moon is always whole,

let me hold you in the nest of my heart.

_________________________________

Glossary

TOOLOOL, TOOLOOL

Blue jay: A bell-like call of two parts, both

on the same pitch. Call and response in

courtship flocks.

WHEEDELEE KUEU KUEU KUEU

Blue jay: Given during courtship and nest building.

CHICKADEEDEE CHICKADADEEDEEDEE

Black-capped chickadee: Given by a bird

that has become separated from the flock, or

given after a disturbance has dispersed the

flock; has the effect of bringing the flock

back together.

CHIRUP CHIREEP CHIRUP

House sparrow: Given by the male when he is