POETRY

Self-Portrait as Nic Martinez

by Nicholas Reiner

as another person, as an other, same me or different me, smart kid

or not as smart kid, or smarter kid, beans & rice, more beans & rice

& the same walk down the street in Wilmington to Foster’s Freeze

for dipped cones so not so different me, some quiet magic, stalks of light

undone at morning & I would be grapefruit I would be starfruit

I am a kind of stonefruit. No,

I am a kind of stone. Entonces it would still be me, same gnawed me, same brown

stone

my mom’s name in this country is the one sacrificed,

laid down así que todo sería el mismo

same trees & streetlights & las mismas voces

or this: nothing would have been the same

Nicholas Tino Reiner is an American poet of Mexican heritage. His debut poetry chapbook Levitations is co-winner of the inaugural Alta California Chapbook Prize, available in a bilingual edition from Gunpowder Press. His poems appear in Spillway, Aquifer: The Florida Review Online, Western Humanities Review, Zocalo Public Square, and elsewhere.

Nicholas Tino Reiner is an American poet of Mexican heritage. His debut poetry chapbook Levitations is co-winner of the inaugural Alta California Chapbook Prize, available in a bilingual edition from Gunpowder Press. His poems appear in Spillway, Aquifer: The Florida Review Online, Western Humanities Review, Zocalo Public Square, and elsewhere.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

POETRY

Why can’t people just ask me about my manuscript?

by Crystal AC Salas

A male stranger

at a mutual friend’s baby shower

asks me when I’m next?

In my dream,

I am always looking for my son

in the park.

This time, he has run from me

to play with the others.

As I walk forward,

the park is empty,

his brown body wiped from the grass

like a fingerprint.

I hear his laughter

but cannot see him.

The layer of his absence splicing

through a life I thought I had

rendered. A photoshop trick.

I don’t go to the park after sundown

because I am a woman. I tried to forget

once, but found myself saying “no

thank you” to a man who tried

to pull me into his car.

I walked briskly, my lungs filled

with night and worrying

if I had declined kindly enough.

In my dream, I run from a man.

Sometimes one I have known,

sometimes one

I have yet to meet.

I run down the concrete,

my ankles unlacing

from my legs. I try

to scream but my throat vibrates

a library hall.

The women in my poetry class all confess

we have been having the same nightmare

for years: half-born babies

dropped into a world that eats us whole.

I dream in reruns: a goldfish

I can’t keep alive.

I forget to take it out of the carnival bag.

It decays in its own dirty water—

a floating epidermis of orange rot.

In another, it makes it to the bowl

to be remembered but ineffectively.

I fail to know what it needs

to stay alive.

I grieve

But it is not the end of all dreaming—

For my poems and their ghosts

I am a field.

I am no container

for this life.

Crystal AC Salas is a Xicanx poet, essayist, educator, and community organizer. Her poetry chapbook Grief Logic is co-winner of the inaugural Alta California Prize, from Gunpowder Press. She has work in Alta Journal, Northwest Review, [PANK] Magazine, World Literature Today, Chaparral Poetry, Acentos Review, and others. A founding member of the BreakBread Literacy Project, which elevates the voices of young creatives under twenty-five, she serves as poetry editor for BreakBread Magazine. She holds an M.F.A. from University of California, Riverside and is the recipient of a 2021-2022 California Arts Council Established Individual Artist Fellowship.

Crystal AC Salas is a Xicanx poet, essayist, educator, and community organizer. Her poetry chapbook Grief Logic is co-winner of the inaugural Alta California Prize, from Gunpowder Press. She has work in Alta Journal, Northwest Review, [PANK] Magazine, World Literature Today, Chaparral Poetry, Acentos Review, and others. A founding member of the BreakBread Literacy Project, which elevates the voices of young creatives under twenty-five, she serves as poetry editor for BreakBread Magazine. She holds an M.F.A. from University of California, Riverside and is the recipient of a 2021-2022 California Arts Council Established Individual Artist Fellowship.

ESSAY

Celebrating the Years, Turning the Tide, and Living on Sesame Street

by Jimin Han

The new year has gotten off to a shaky start. I refer, of course, to the mass shooting in Monterey Park and Half Moon Bay. I also mean the devastating number of mass shootings since the new year that continue to plague us.

In my family, both new years were celebrated. The Gregorian one and the Lunar one. My mother and her sister, my aunt, were very much on my mind through the start of both celebrations this time around.

In my family, both new years were celebrated. The Gregorian one and the Lunar one. My mother and her sister, my aunt, were very much on my mind through the start of both celebrations this time around.

First let me tell you about my mother. She always made tteok guk, rice cake and dumpling soup, and undertook extensive cleaning of the house on the day before both new year holidays, literally sweeping out the old to allow the new to enter our home. In my attempt to follow tradition, I move furniture to vacuum behind it and mop the floors, get out my broom and sweep with zeal. I did this on December 31 and again the night before January 22. I’ll never come close to my mother’s cleaning skills, but every year I try my best. My resolution—an American tradition– is to not sweat the small stuff.

In terms of American traditions, I learned them through the world around me, with television playing a big part early on. I was four years old when we immigrated to the United States from South Korea. By all accounts I was a talkative child who had the nickname “Chamseh,” which means songbird. Tells you

how much I talked, and that I sang too! My parents couldn’t afford to send me to pre-school. On our small basic television set with an antennae– this was 1970—they let me watch Sesame Street every day. The show taught me English so well that I had a seamless transition to kindergarten, a year later. Writing and reading became my favorite subjects in school right from the start.

Fast-forward fifty-three years. Melanie Schmidt, the producer of the audiobook for my new novel, The Apology, invited me to recommend voice actors. It was a challenge that required someone who could speak both English and Korean fluently, sound like a one-hundred -five-year-old and a twelve-year-old, with a variety of characters of different ages in between. I asked Theresa Choh-Lee and HJ Lee, founders of Korean American Story, for their suggestions. For a decade, their community-building creative project has documented the Korean American experience through personal stories. They immediately recommended Kathleen Kim for the role. She is the performer behind the newest Muppet on Sesame Street, Ji-Young.Who would have thought it would come full circle this way? Sesame Street has returned to my life through my new novel. My four-year-old self is jumping up and down. My mother would be happy for me too.

I promised you that my aunt, my mother’s sister, was also on my mind at the beginning of this year. She teaches line dancing in Fairfax County, Virginia. I thought of her when I learned of the dance hall in Monterey Park where eleven people perished. This was exactly the kind of place where she dances and celebrates with her friends and students. Who is to say this could not happen to her or to any of us in any social situation? We know it can because it’s been happening and continues. This kind of fear can be paralyzing. My aunt, I have to tell you, is fearless. She’s stood up to Japanese soldiers during colonization, survived displacement in the Korean War, immigrated to the United States and killed actual rats with a broom in a house she was making into a home with very little money. When I listen to her, I know this epidemic of gun violence is a tide we can turn.

Jimin Han was born in Seoul, South Korea, and grew up in Providence, Rhode Island; Dayton, Ohio; and Jamestown, New York. Her work has been supported by the New York State Council on the Arts. She is the author ofThe Apology and A Small Revolution. Additional writing of hers can be found online at American Public Media’s Weekend America, Poets & Writers, and Catapult, among others. She teaches at The Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College, Pace University, and community writing centers. She lives outside New York City with her husband and children.

Jimin Han was born in Seoul, South Korea, and grew up in Providence, Rhode Island; Dayton, Ohio; and Jamestown, New York. Her work has been supported by the New York State Council on the Arts. She is the author ofThe Apology and A Small Revolution. Additional writing of hers can be found online at American Public Media’s Weekend America, Poets & Writers, and Catapult, among others. She teaches at The Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College, Pace University, and community writing centers. She lives outside New York City with her husband and children.Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

STAFF ESSAY

Wrapping Up a Life

This essay was posted on December 28, 2022 at www.caiemmonsauthor.com.

by Cai Emmons

introduction by Paul Calandrino

Cai Emmons and I met at the Community of Writers in 1993. We were both participants, though later she occasionally worked on the staff. We were instantly drawn to each other, became close friends, and eventually lovers. We didn’t know then that we were soulmates. Cai was my hayati, my life. She lived an extraordinary life.

Cai Emmons and I met at the Community of Writers in 1993. We were both participants, though later she occasionally worked on the staff. We were instantly drawn to each other, became close friends, and eventually lovers. We didn’t know then that we were soulmates. Cai was my hayati, my life. She lived an extraordinary life.As I write this, it has been four weeks since Cai ended her life through Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act. We were surrounded by family and friends, and those who couldn’t travel to Oregon joined us virtually. Oregon law requires that the patient administer the life-ending drugs herself. I held the syringe steady as she worked the plunger. Her other hand was wrapped around mine. And it occurred to me later that this was like the moment in the wedding ceremony when rings are exchanged and the wedded hold hands. It was as if I were joining Cai in death.

She had moved the date of her death up two weeks, due to her worsening condition and a particularly brutal visit to the E.D. on New Year’s Eve. We never made it to the getaway Cai mentions in her farewell letter. There was no “next week.” But there was love. I feel it to this day. 1/30/23

•

A good writer friend calls me a “completionist” because I insist on finishing a piece of writing even when I know it isn’t any good, whereas she is able to abandon work as soon as she senses it stinks. She is right about me; I can’t bring myself to toss something before it has a clear ending.

This completionist compulsion is in full bloom now as I prepare to die. Because I’ve known about my imminent death for a couple of years now, I’ve had plenty of time to prepare for it, to try to tie up the loose ends of my life. Initially this meant making sure I had an up-to-date will. It meant marrying the man I adore who I’d been living with for over twenty years. It meant having candid conversations with my son, sisters, and dear friends. It meant making sure Paul had all my passwords. Much of that flurry of activity happened almost two years ago, shortly after my diagnosis, and I had the illusion back then that I might move on and devote the rest of my days to thinking and remembering and dreaming while listening to music or books on tape.

What a surprise it was to see how life carried on and so did I. Those early efforts barely scratched the surface of wrapping things up. There were so many old friends, dear friends, I still needed to talk to. There was a novel-in-progress I needed to finish, a newsletter to write, two new books coming out that I needed to promote as well as I could. There were also household projects to complete, and Paul and I needed to spend as much time together as we could. I wanted to devour the world, do it all, even with the end in sight.

When I was in college a group of students formed a band called Entropy that played at many campus events. It was my introduction to the concept of entropy (I had not, to my chagrin, studied physics). But the concept—which for a layperson means gradual decline into disorder—took root in my consciousness and has colored much about how I have seen the world since then. It is the natural order of things to sink into decline, something I’m reminded of every time I walk down the road and see several sagging moss-covered buildings being reclaimed by the earth. Whoever owns them has failed to maintain them, and there will soon be little sign of them at all. It is also in the nature of living things to die and disappear. Much of our lives are devoted to pushing back against such entropy—shoring up buildings and our own bodies against their inevitable collapse. For a while it works, but in the end it’s a futile task.

When I was teaching, I emphasized—and pardon me for repeating myself, I know I have said this before—the importance of accepting uncertainty as part of the writing process. Keats wrote about this in a letter to a friend: accepting “negative capability” means setting aside “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” This is, of course, difficult to do, and one can’t do it in writing without doing it in life. When I examine my efforts to wrap up the loose ends of my life, I see that I’ve failed to fully accept negative capability. My efforts seem to be an irritable reaching for certainty and a neat conclusion to something—a human life—that will never be neat. Wrapping things up will not overcome the entropy of my own life, nor will it alter the nature of what that life has been.

What is a life, after all? It is not a novel. It is not an artifact. It is an energetic enterprise in which atoms cohere for a while before the organism they have been part of dies and decomposes, and the atoms take their energy elsewhere. If I had died suddenly in a car accident and had no time for goodbyes or clearing my inbox, would it make a difference in the life I have led? I doubt it.

Trying to wrap up my life in its final weeks has left me busier than I have possibly ever been. In addition to trying to finish the new novel in the next week, I have a list of letters and emails to write, daily Zooms or visits, a newsletter and blog to compose, a “death event” to plan, etc. Fortunately, Paul and I will going away for a few days in early January to take a deep breath together.

Part of me would like to be able to step back and say no to everything, but each time I consider that I realize I don’t really want to. I will die as I have lived, saying yes to everything, trying to bring closure despite knowing that neat endings are an illusion.

See you next week.

Love,

Cai

Cai Emmons (1951-2023) was the author of six novels—His Mother’s Son, The Stylist, Weather Woman, Sinking Islands, Unleashed, and Livid—and a story collection, Vanishing. She held a BA from Yale University and two MFAs, one from New York University in film and the other from the University of Oregon in fiction. Before turning to fiction, Emmons wrote plays and screenplays. Winner of a Student Academy Award, an Oregon Book Award, and the Leapfrog Global Fiction Prize, and finalist for the Narrative, The Missouri Review, and the Sarton awards, she taught at a variety of institutions, most recently in the creative writing program at the University of Oregon.

Cai Emmons (1951-2023) was the author of six novels—His Mother’s Son, The Stylist, Weather Woman, Sinking Islands, Unleashed, and Livid—and a story collection, Vanishing. She held a BA from Yale University and two MFAs, one from New York University in film and the other from the University of Oregon in fiction. Before turning to fiction, Emmons wrote plays and screenplays. Winner of a Student Academy Award, an Oregon Book Award, and the Leapfrog Global Fiction Prize, and finalist for the Narrative, The Missouri Review, and the Sarton awards, she taught at a variety of institutions, most recently in the creative writing program at the University of Oregon.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

LYRICAL ESSAY

Bone & Skin

by Suzanne Roberts

1.

I tell you I’m getting a tattoo to cover my scars. Some kind of tree, perhaps, the branches reaching across one scar, the roots wrapped around another. A living thing. An ancient bristlecone, a saguaro, a juniper, purple with berries. “You’re allergic to juniper,” you say, and I nod. I do not ask, “But isn’t that the point?” And it isn’t true—I don’t really want the tattoo. I trace the scars with a fingertip, the thin, hard edge remembering the blade. The evidence of fracture, wound, fragility. The fine white light, the pucker of skin, the pink star where the bone broke free.

2.

I am crying again, and you tell me you’re worried about me, that I carry too much grief. “You let it accumulate,” you say, “instead of letting it go.” Sometimes I think about this, and I am angry. Other times, I wonder if you’re right. I know with each new loss, there’s a heaviness in me, dressed in too many layers, wrong for the weather. You ask, “But what will happen to you as the years wear on? There’s nothing but loss ahead.” I do not say holding onto these losses scares me less than trying to let them go. I do not say the weight of them prevents me from floating away and disappearing. I do not say I am more alive—with pain yes, but alive—every time someone else I love has died.

3.

Sometimes when we’re making love, I can’t help but think about our skeletons, foundations beneath flesh: the jutted pelvis, iliac crest, sculpted like a seashell. Your now-fleshy hands grasp the mantle of my hips— the skeletons, fibrous and calcified, will soon enough be stripped clean without the canvas of skin, red strip of muscle, the jellied yellow tissue. These woven bones, at last, shining naked. The hips, ribs, and skull—the inside finally out. The eye sockets emptied—no longer a lookout. Like the last page of a book, holding the air of already having seen. Emptied of recognition—emptied of this moment, this brief intermission of tension and delight, the silver orgasmic quiver of the almost already dead.

4.

My mother once told me her pain felt better only when she cried out—her groaning swelled to howl as the cancer ate away her vertebrae. When the pitch of her pain startled me, my own body betrayed me, too—I had to stifle a laugh. I understand the element of surprise can shake us into tears or to laughter, but still—there is no way not to burn with shame.

5.

When I cry out in pain in the small hours following the accident, you do not laugh. But you want me to stop. “I’m afraid the neighbors will think I’m beating you.” That makes me laugh, between my cries, even if it isn’t funny. My mother was right—the screaming gives the body its distraction. And also its metaphors: I tell you the pain is a shooting star—a hot, white, bolt ripping through skin and bone. It is the inside of a creature’s jaw, the crunch of locked fangs. You beg me to take the pain pills, but I refuse the dull throb, wanting instead the sharp truth of it—the involuntary breathless howl, present and primal—the laughter, orgasm, tears.

Suzanne Roberts is the author of a collection of lyrical essays, Animal Bodies: On Death, Desire, and Other Difficulties(Longlisted for the 2023 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay), an award-winning travel memoir in essays Bad Tourist: Misadventures in Love and Travel(2020),and a memoir Almost Somewhere: Twenty-Eight Days on the John Muir Trail (Winner of the National Outdoor Book Award, 2012), as well as four collections of poems. Named “The Next Great Travel Writer” by National Geographic’s Traveler, Suzanne’s work has been listed as notable in Best American Essays and included in The Best Women’s Travel Writing. Her work has appeared inThe New York Times, CNN, Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, The Rumpus, Hippocampus, The Normal School, River Teeth, and elsewhere. She holds a doctorate in literature and the environment from the University of Nevada-Reno, teaches in the low residency MFA program in creative writing at UNR-Lake Tahoe, and splits her time between South Lake Tahoe and an old green van named Shrek. More information can be found on her website: www.suzanneroberts.net

Suzanne Roberts is the author of a collection of lyrical essays, Animal Bodies: On Death, Desire, and Other Difficulties(Longlisted for the 2023 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay), an award-winning travel memoir in essays Bad Tourist: Misadventures in Love and Travel(2020),and a memoir Almost Somewhere: Twenty-Eight Days on the John Muir Trail (Winner of the National Outdoor Book Award, 2012), as well as four collections of poems. Named “The Next Great Travel Writer” by National Geographic’s Traveler, Suzanne’s work has been listed as notable in Best American Essays and included in The Best Women’s Travel Writing. Her work has appeared inThe New York Times, CNN, Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, The Rumpus, Hippocampus, The Normal School, River Teeth, and elsewhere. She holds a doctorate in literature and the environment from the University of Nevada-Reno, teaches in the low residency MFA program in creative writing at UNR-Lake Tahoe, and splits her time between South Lake Tahoe and an old green van named Shrek. More information can be found on her website: www.suzanneroberts.net

TRIBUTE

Gerald Stern: Words of Life in Him

by Robert Lipton

Gerald Stern was a great, ruffled, profane/elegant poet from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He recently passed away and there have been and continue to be stirring, profound things said about him. He was from the “old” generation, just about emerging at the same time as the Beats but a different, more global sensibility, informed by being one generation away from the early twentieth-century eastern European/western Russia Jewish immigrant wave. His was the Depression, WWII, holocausts, cold wars, McCarthyism, the ‘60s. He wrote like Chagall painted, without the pixilating religious iconography, colorful, disorienting, surprising, familiar — because he was an oracular uncle, like a Walter Cronkite of the soul — the news you didn’t know you needed to hear.

But most of all, with a deep sense of agape, Whitman as sung by a sideshow barker, strange colors and flying goats. And the damn wars, all the wars. He was an actual boxer and a figurative one as well as a labor union head, and he could lull you in — give you a sense that you were going to hear another story about the good-old-days, HA! He would tell you that your granny was a sadist, his too – that memory, if it didn’t destroy you, it would abandon you or beat you to death with inexhaustible obsessions.

Let’s take a look at one of his classics, also the name of one of his most known books, Lucky Life. The first line: “Lucky Life isn’t one long string of horrors.”

Instead of a listing/narrative description/affirming exaltation, we get the low-rung “optimism” of life not being one long string of horrors, which begs the question “Perhaps it is?”

This is a self-soothing, super-observed revery with the ultimate sense that it’s lucky we have a life, recursively, that we can crabwalk, stumble between observations that seemed whispered, shouted, silent. And the specificity of place linked to feeling.

My dream is I’m in the Eagle Hotel on Chamber Street

sitting at the oak bar, listening to two

obese veterans discussing Hawaii in 1942,

and reading the funny signs over the bottles.

My dream is I sleep upstairs over the honey locust

and sit on the side porch overlooking the stone culvert

with a whole new set of friends, mostly old and humorless.

This is a “noticing” with extreme prejudice. His is the dream of the quotidian, twisted into desire, rueful acceptance, and he THEN asks the ocean’s waves for his memories.

His work is pretty much in line with how he lived. I hadn’t met Jerry before, didn’t know he was even called Jerry, knew exactly six of his poems, and that he was the opposite of couth, seemed elemental, garrulous. I went to the Community of Writers poetry week that time, 2002, (my second time) drawn to the workshop, to him – a bit of the Zorba the Greek, Jerry the Jew, American non-practicing/cultural lefty vibe, but not just….

I’d had a very intense year, processing my tiny experience of war — I had spent one million years (six weeks) doing humanitarian work in Palestine — and here was a place to rest, with a rumpled man who sang and snarled, laughed in his workshops. Things happened there that first time, crying (not him), a poet walking out, a slammed door, a scream, a stupid amount of embarrassed guffawing (not him). Wasn’t sure what/how to think.

I helped run the Beyond Baroque weekly poetry workshop in the late 1980’s, early ‘90s, in Venice, California. Some days there would be chairs thrown, police called, laughter. In other words, Jerry was home cooking for me. He cared way more than then the typical, and in a place of poetry, where one was to care, this was bracing! Poetry mattered far more than poet’s even.

This isn’t what I thought then.

I’ve put the story together here, I suppose, to explain the inexorable pull/comfort I felt. Jerry, in his poetry, in his reading of his poetry, allowed me into a secular Jewish American vernacular that I, a generation or so removed, also experienced. We became friends, as if we had always been. We had things to talk about apparently. This conversation is now over twenty years old, a third of my life, about one-fifth of Jerry’s. He had a whole world, worlds of life in him, which I only dimly knew about.

About a year or so after the Poetry Week, Jerry and I set up a reading and seminar at Live Oak Park in Berkeley, part of the Berkeley Art Museum’s literary arts director (I was the founding director). His friends came from all over, poets, his students, people who needed him to read manuscripts, (Did I mention poets?). As I drove him to and fro he’d mention things like boxing, being shot in the neck, union leadership, bowling — “Jerry, what was that middle thing, the getting shot in the neck?” — and he would be, “Well, it was no big thing, hit the fleshy part of my neck….scared the hell out of the woman I was with, she had beautiful eyes…” I also organized another reading in 2014, (Albany Library and Poetry Flash sponsored) his last time on the West Coast, and hundreds showed up. Bob Hass elegantly introduced him. Although Jerry had a bad back, he was in hog heaven, we visited his friends out here, and there was an indoor swimming pool he loved. We even went up to the late Jane Mead’s vineyard/house on Atlas Peak in Napa.

There was Jerry’s major street cred, but his lefty politics (something we also shared) was worn lightly, not the commitment, but the eschewing of strident endorsement, between the laughter and raised middle finger to totalizing power. It shadowed his poetry as well. And that’s Jerry forever, his poetry, his broken, bawdy stories, the power of his words, his secular rabbinic sadness/joy. Of course, I’ll miss his laughter in real time, but man, oh, man, his life, his words, his “Get off the sidewalk if you don’t like my driving,” his Mr. Magoo crazy, his laughter still, his friendship.

Robert Lipton was a recent poet laureate in Richmond, CA. His poetry book, A Complex Bravery, from Marick Press, has not received a bevy of awards. He works as a spatial epidemiologist.

Robert Lipton was a recent poet laureate in Richmond, CA. His poetry book, A Complex Bravery, from Marick Press, has not received a bevy of awards. He works as a spatial epidemiologist.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

When I attended the Community of Writers, the person who saw me most—and I mean qualitatively here, not quantitatively—was Gill Dennis. I was enrolled in his famous workshop, which compelled us into uncomfortable territory in the name of good character development: we were asked to write down our moments of greatest fear, shame, and pride as adults, then look for the thematic threads that bound those moments together, weaving tightly our life’s code of values. Then, taking a step back, we could note more globally what makes for credible character work.

It was before we even got into this exercise that Gill saw me most, however. He saw me most in a pre-class moment, when he complimented me on something or other and, leaning in conspiratorially, I said, “Well, this means a lot, you know, because you wrote the screenplay for one of the most important movies of my youth.”

He leveled a Gill Dennis gaze at me, a Cratchit-did-you-just-ask-me-for-coal arch gaze, huffed playfully, then replied, “Don’t even say it. I already know.” We proceeded to talk about Return to Oz for the next ten minutes, without ever naming the film or its actors.

I watched Return to Oz so much as a kid that it worried my mother. At the time, I couldn’t say why I deeply identified with it, but now the parallels are apparent enough. When the movie opens, Dorothy’s being assessed for shock therapy to deal with her memories and visions of Oz, and when she manages to escape this fate and Kansas for a second time, she lands “safely” back in an Oz that’s been overrun in her absence, full of ruins and rusty, squeaky monsters. I was sick a lot (allowing me even more opportunity to watch the movie), I was an anxious only child with a rich internal life that mapped onto nothing externally and landed me outside the social circles of my peers, and my home territory was the arroyo at the end of my street, a riverbed that connected eventually to the LA River and flooded every couple years, the El Niño rains clawing downstream everything from old TV sets to ovens to Pontiacs. My playground was sand, invasive stands of bamboo, an ever-present threat of tetanus, and the artifacts of other lives. It was alien and beautiful, a museum for me to curate for the owls that roosted along the cliffs skirting the arroyo, for the lizards that wriggled out from under the sand when I unknowingly stepped on them, for the ravens and summer tadpoles. When I ran home from playing there, Return to Oz helped me believe it was OK that I felt more comfortable walking a post-human landscape than the halls of civilization.

This trash river romance of my childhood is not unique to me, but I do think it holds a special significance for people here in Los Angeles County. The LA River—this strange, essential thread woven through the heart of the city—is a cement cipher onto which we’ve projected our feelings about nature, animism, folly, torrent, wrath, apocalypse. Building it turned a floodplain into a city, but in the process helped ensure that a drought-prone region would flush 100 billion gallons of stormwater directly into the ocean annually. It is our only thoroughfare not beset by traffic: in movies, it’s often the only place in the city to go if you want to go fast, either to race roadsters or to escape the Terminator. One time, a volunteer clean-up crew found a human skull in the LA River and, having no clearly better alternative, put it back. Our civic priorities when it comes to the LA River have frequently been a metonymy of our civic priorities at large. It is at turns our city’s moment of greatest fear, shame, and pride.

Growing up, I had another reason to find connection with the LA River: a substantial portion of the water feeding the river in non-rainy seasons, allowing kayakers to safely paddle the Elysian Valley stretch in the summer months, comes from Tillman Water Reclamation Plant in Van Nuys, a wastewater treatment plant where my father worked as a mechanic for more than two decades. Before Affirmative Action was struck down at the state level, the City of LA annually sponsored Bring Your Daughter to Work Day, which the guys in the tool shop lovingly renamed Drag Your Daughter to Work Day, and once a year I would get up with my dad at 4:30 AM to make the drive into work with him. He would take me around to see the water screws, the blower room, the open vats and labyrinthine tunnels of the plant, then when he needed to do some work he would release me into the Japanese garden next to the plant’s administration building, which over the years has also served as Starfleet Headquarters and Pauly Shore’s entry into Bio-Dome. One time, parked in front of a computer terminal while he completed a work order, I typed out a story about a duck that lived in the Japanese garden. Someone found it later and ran it in the plant newsletter. So, you could argue my life as a writer began inside the wastewater treatment plant feeding the LA River.

In the years—if we’re lucky, decades—to come, LA will be forced to reckon with its greatest immutable truths and unsustainable choices, and looming large among them, always, is the subject of water. The state’s water table has dropped so much that California’s entire Central Valley has sunk almost thirty feet in the last century (for a truly breathtaking look at the history of water usage in California, I recommend Mark Arax’s The Dreamt Land: Chasing Water and Dust Across California). LA is pulling half our water from the Colorado River at this point. We split that dependency with five other states, all of which the water has to traverse first in order to reach us. For half the water we consume, then, we are the last state in line. Attempts to use recycled water here in the past have been foiled by “Toilet to Tap” propaganda, which my father, as a cleaner of water, always took personally. Water recycling technology is so good at purifying water at this point that facilities have to add minerals back into the water afterward in order to make it easier for our bodies to absorb.

Then, again, there’s the LA River, and that little matter of the 100 billion gallons we shunt out to sea annually. There’s a very real reason to gaze across this massive concrete channel, which some rankle to call a “river,” and see a post-human landscape reflected back in it. We literally built ourselves a highway to drought. And there’s an equally real sense, in the stories we tell about this city, that we aspire toward that post-human landscape. Call it penance, warning, or a basic desire for closure. I just finished a short story collection called Cataclysm County, CA, and the general thesis of it is that thanks to drought, fire, and earthquakes, Los Angeles County was already surreal as hell before pandemic and climate change, but now, truly, all bets are off. (It doesn’t abate the surrealism any to grow up in places you then rediscover, time and again, as the backdrops to apocalypse in film and TV.)

Happily, in this current surreality that we all share, a lot of very smart people are navigating a gargantuan system of authorities, departments, districts, counties, cities, even coagulating their voices at the state level to address our city’s tenuous water future. One of them is my friend, Lauren Ahkiam. Lauren is the director of Water Justice LA, a project of LAANE, the nonprofit where we work together. She’s been advocating tirelessly with partners across the region for policies like Measure W, which passed in 2018 and taxes non-permeable land in LA County (those big asphalt parking lots that dump oily rainwater into the LA River, for example) to pay for stormwater capture projects. She spent the better part of last year deconstructing and demystifying the state budgeting process so that we and other ally groups across six counties could advocate for money for water, and it worked: we won $2 billion in dedicated funds for drought resilience, water affordability, and clean drinking water, with another $1 billion for other water investments. Before that advocacy, the initial January budget proposal had just $500 million dedicated to drought resilience, a number nowhere near commensurate with the crisis. What that extra money buys us is a shot at a future where we can capture and recycle water at a scale that is both sustainable and equitable, a shot at a future that is a little less rusty, a little less squeaky, a lot less post-human. Whether we capture that shot, and build something that takes a lesson or two from the LA River, will largely be a matter of relentless perseverance and imagination, two things a writer can certainly appreciate.

Gill Dennis of course couldn’t have known the particular parched landscape of my childhood imagination, but it was enough to be clocked by him and his eyebrow as a weird solitary girl of a certain age who, at a critical stage of her development, found and loved another weird solitary girl he’d helped write into the world. This is the glorious kinship of writers: the recognition that, even if we haven’t met before, our imaginations have. It’s sustaining, enough to keep me fighting for something more.

Kristen Leigh Schwarz grew up in Newhall, California, and holds an MFA from UC Irvine, where she received the MacDonald Harris Award for Fiction and a travel award from the International Center for Writing and Translation to work in Mexico. Previous stories have appeared in One Story, the Santa Monica Review, The American Literary Review, and Collateral, among others. Her story, “Emperor of Umbrellas” reps Santa Ana, California in the anthology Orange County: A Literary Field Guide.

Kristen Leigh Schwarz grew up in Newhall, California, and holds an MFA from UC Irvine, where she received the MacDonald Harris Award for Fiction and a travel award from the International Center for Writing and Translation to work in Mexico. Previous stories have appeared in One Story, the Santa Monica Review, The American Literary Review, and Collateral, among others. Her story, “Emperor of Umbrellas” reps Santa Ana, California in the anthology Orange County: A Literary Field Guide.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

MEMOIR

Self Portrait as a Human Interest Story

Excerpted from Longreads

by Emi Nietfeld

If you’ve read a newspaper, you know me: I was the high school senior who overcame unbelievable odds to win swell prizes.

They could have shot a made-for-TV-movie: gone dad, hoarder mom, foster care, homelessness, so much adversity the Horatio Alger Association gave me $20,000. I snagged $10,000 more in a writing contest, won $3,000 to visit Europe, and landed a full ride to Harvard (valued at approximately $210,000, plus $1.6 million in expected extra lifetime earnings, and 27 free, corporate-branded water bottles).

They called me “one-in-a-million.” I was proof of the American dream. On May 24th of 2010, when I smiled in my gray cardigan in the Saint Paul Pioneer Press, I carried the torch of an eternal narrative.

Until five weeks later, when I was raped.

***

What does it take to become a success story?

Start studying for standardized tests as soon as you leave home at 14 years old. After the narrow paths littered with dog shit snaking through your house, marvel at the institution’s clean floor. Shock yourself with your focus when no mice dash across the room. Decide not to feel sad when your mom can’t get her act together; the foster family lives in a good school district.

They could have shot a made-for-TV-movie: gone dad, hoarder mom, foster care, homelessness, so much adversity the Horatio Alger Association gave me $20,000.

Please a parade of adults: the guidance counselor in shiny pants who lets you take three Advanced Placement classes sophomore year, the doctor who sends you to summer camp, the camp instructors who help you get a scholarship to boarding school. Write letters to your teachers that you’ll never send. In them, vow to win all the awards. Swear that you will become the greatest student of all time so that one of them will take you home and keep you.

Play a good house guest during breaks so your friends’ parents and your mentor put you up.

When you run out places to stay the summer you’re 16, curl up in the backseat of your rusted-out ‘92 Corolla. Clutch the gray cardigan you carry everywhere.

Remember the bedtime story your mom used to tell about a stuffed animal that became real when loved. Pray that becoming a human interest story will make you human.

***

If you assumed I always knew the rules, you’d be wrong. The summer before my senior year of high school, I sat in the library and pored over stacks of advice books. They described the admissions committee as a room full of benevolent grown-ups. “Just be yourself,” they instructed, “Show the committee who you are.”

Who was I? I was sick all the time back then. Once, I stood up in Calculus and puked into a trashcan; I sat back down and no one said a word. I got sick while staying with a cousin and woke up on an air mattress 16 hours later, SAT book propped open next to my face. During a week with my mentor, I fell off a bike and went to AP Chemistry camp six days later, concussed. I never took a day off. But when I got the flu, I longed to have someone sit beside my bed and read me vocabulary words and assure me I was good enough even when I wasn’t productive.

I couldn’t imagine a better fate than revealing myself to The Committee and having them accept me. When I wanted to give up, The Committee was my conscience, urging me on. When no one in the world knew where I was, they were my guardian angels. And if it all worked out, they would be my saviors. The fat envelope they sent would lead to so many hugs, so many warm congratulations. The desire felt like an explosion causing my chest to cave in.

But when I got feedback on my essays, I learned my shot at upward mobility hinged on the correct marketing. The girl who hadn’t showered in a week and stank of anxious sweat — she wasn’t going to cut it. I had to embody overcoming.

I flattened my past into a one-page Letter of Extenuating Circumstances. I stripped my essays of potential red flags such as depression, loneliness, and poor personal hygiene. At the interviews for Harvard and Yale, I wore my gray cardigan and told the rehearsed version of my life story. I shed neat little tears at all the right times, exhibiting remarkable composure coupled with the appropriate degree of vulnerability.

By the time I applied for the awards described by the Traverse City Record-Eagle, I wasn’t just detached: I’d bought into the narrative they’d tell. I stuffed manila envelopes for writing contests, filled with each trauma and secret I’d once held sacred. In 500 words, I compared myself to Buzz Aldrin, second man on the moon. I completed a checklist of challenges I’d faced. I called this “adversity bingo” and every time I described it, I laughed, giddy on the hope I could cash in on my sorrow.

***

What do you do when you get into Harvard?

Scream. Let it echo in the computer room. Run down the escalators of the Seattle Public Library, out into the drizzle. Scream, “Yes! Yes! Yes!” Let the passersby stare.

Visualize your new life: a Frappuccino every day, snow boots that don’t leak, air conditioning, vacations in France, people looking at you and seeing a Harvard student instead of another greasy-haired street kid.

Pull your sweater tight around you as it gets damp from the rain. Jump up and down until it exhausts you. Jump up and down some more. Slump on the floor of the library entryway. Go back to the hostel where you’re staying alone over spring break.

The next night, sleep in the airport before your flight back to boarding school. Wrap your cardigan around your face to block out the lights of the baggage claim. Pray that no one hurts you. Let your loneliness baffle you: you won the college-admissions lottery. Shiver considering the odds. Promise yourself this joy will never fade.

***

“Stick to the awards,” my boarding school’s publicity guy instructed me before I talked to the reporters. He warned me not to mention my family or the contents of my prize-winning essays. He suggested I smile into the receiver to sound friendlier.

I did as I was told. By the end of May, I felt like a champion had replaced the old me.

That spring, even strangers gave me things. An elderly Republican bought me a Crimson sweatshirt and photographed me wearing it for her charity’s promotional pamphlet. A businessman gifted me a set of luggage for all the traveling I’d surely do. I told a banker my life story and she wrote me a check for the most money I’d ever seen.

My life felt like a parable of the rewards of hard work. My doctor and I exchanged happy emails filled with exclamation points. My mentor bought me a green gown. The Scholastic Art and Writing Awards flew my mom and me out to New York. In our fancy hotel room, we were a family reunited. I bowed on stage at Carnegie Hall. When a judge hung a gold medal around my neck, the weight of it completed me.

At the afterparty for the donors, I gabbed while smiling effortlessly. I gushed about my summer plans backpacking Europe to a reporter from The Observer. The CEO of Scholastic Books gave me his business card. “I read your stuff,” he said, “It’s brave.”

“All I have are my secrets,” I replied. Secrets soon to be anthologized in The Best Teen Writing of 2010. We shared a laugh.

Then, I saw my mom gesturing wildly, bragging about her daughter. It seemed my coup had accomplished the impossible and turned me into a child she could love.

***

How can things fall apart so quickly?

Board your first international flight. Everything you own is in your backpack, but now that makes you a backpacker instead of a homeless minor. Marvel at Europe: the Little Walking Light Men in Berlin, the sleek red train to Munich, the Soviet-era train to Prague. Watch the Danube shimmer as it comes into view out the window of your bus to Budapest. Believe your life, from then on out, will be a parade of wonders, each more fascinating than the last.

Then, three months after getting into Harvard, sit down in the kitchen of your hostel. The 30-something-year-old man working there corners you. No one is around. No one even knows you’re in Hungary.

Fear blazes through you as he pulls his pants down. Picture all the people you’ve placated before. Search his face for any empathy. Plead, “I’m a virgin.”

Hear your voice shake as you say it. Hear your chair bang against the wall as you realize you’re trapped. Hear your whimper as he grabs you, the rapist’s groan as the pain tears into your throat. Hear the echo as he yells at you, “Bitch.”

Statistically, it should have happened sooner: someone’s boyfriend or father, anyone, could have attacked you anywhere, in any airport or guest room. But here? Now? After all of that?

Gag. Choke. Imagine your body bloated with water, floating down the Danube. Wonder if they’ll only look for you because you got into Harvard.

Struggle to breathe. Stay calm. Conserve air. As everything gets dark and blurred around the edges, tally up your winnings. Bargain them away with God, one by one, to make it stop, to breathe again, to live.

The rapist ejaculates on the cardigan you wore in the newspapers. He lights a cigarette and asks, “What’s your name again?”

If the reporters’ questions made you real, the rapist’s question erases you.

“Just kidding, Emi.” He laughs.

Spit hangs from your chin. Tears and saliva coat your cheeks. Snot dangles from your nose in strings. Realize how you look: you’re the opposite of the girl in the newspaper, dignified by her achievements. You feel worth less than a chew toy, less than the pile of trash in your mom’s bathtub, less than a stack of moldy magazines. Worry that this is who you were all along, that all the rapist did was strip you of your packaging.

***

I woke up the next morning the loneliest I’d ever been. My throat hurt so bad I worried I’d never speak again. There’d be no more smiling into the phone, no more men jotting quotes on notepads, no more beaming on the local Fox News. Maybe it was for the best: when I saw a picture of myself on TV, I felt mystified; how could anyone look that elated? Anyway, the news cycle had moved on to the octopus predicting the World Cup.

I wrote my doctor a desperate email. For the rest of the day, I staggered around Budapest, stunned.

I felt like such a failure. I thought I’d bombed the biggest test of my life by not being able to stop the rapist. I stood on a bridge over the Danube. I pressed my belly against the railing and stared down at the shimmering water. I knew that if I fell far enough, all my bones would break at once. Then, I remembered the donors and my mentor and The Committee. Obligation overwhelmed me. I stepped away.

When I checked my email, I found requests for financial aid forms and line edits of “tremendously powerful” poems and confirmation on the right address to send the five-piece set of luggage. But my doctor didn’t reply.

Two days later, still in pain, I called my mom. “I want to go home,” I cried. I felt pathetic as I said it. That was the wrong story. My life wasn’t The Wizard of Oz.

In the story my mom told, The Velveteen Rabbit, the toy gets taken away but as a consolation prize comes to life. At the end of the book, he’s frolicking with the other bunnies in the grass when he sees the boy whose love made him real. The rabbit watches but can never go home.

That’s how I felt when I read my mom’s reply to the news that I’d been assaulted. She emailed me a list of my accomplishments. She paraphrased a quote from The Incredibles: “Stop acting that way, remember who you are!” I had to cheer up.

I knew my success obligated me to respond a certain way. Back in Minnesota, when my doctor asked if I had contemplated suicide, I answered: “I owe too much to too many people.”

When my mentor asked me, “What were you expecting?” I balled my fists and stared at the floor. “It’s not safe. A girl, alone?” As if I’d never felt unsafe during those years on my own. But I couldn’t defend myself: I needed a place to stay. By then, I knew how this human-interest-story stuff worked. When I succeeded, I exemplified triumph. When someone hurt me, I was held responsible for my vulnerability all along.

***

What do you do next?

Wash your sweater. Thank your mentor for her advice. After a week on her sofa, board a bus to Chicago for one friend’s house, followed by another’s. Play a good houseguest. Smile. Say, “Thank you.” Say nothing about the attack. When people ask about your background, say, “I went to boarding school.”

Jolt awake in the night, heart pounding, suffocating. Lay awake replaying, “What’s your name again?” Try, and fail, to figure out why this question upsets you. Take Benadryl and Melatonin, as prescribed, to knock you out. Fail at sleep, too.

Confess as much as you can muster to University Health Services. Complain about your poor sleep and your bad mood and your negative attitude. In response, receive time-management coaching. After exhibiting so much resilience and self-sufficiency, experience the consequences as moral failures.

I knew how this human-interest-story stuff worked. When I succeeded, I exemplified triumph. When someone hurt me, I was held responsible for my vulnerability all along.

Berate yourself for not getting Phi Beta Kappa. Hate yourself for not becoming a Rhodes Scholar. Chastise yourself for not founding a charity.

Do the only thing you know how to do: work harder. Study computer science. Smile behind a laptop in The Harvard Gazette. Pantomime “girl brainstorming with multicultural team” on the School of Engineering website. Get a job at Google. Line up your eyebrows with your Ivy League husband for The New York Times wedding section.

See your photograph and remember how wet the spit felt smeared across your face. Remind yourself you were an archetype all along, valuable only as long as you fit the narrative.

***

After the rapist mocked me, he made me kiss him, as if I appreciated what he did or owed him for letting me go. I think about his lips on mine every time someone implies that the adversities I overcame indebted me to eternal gratitude for my good fortune.

Thank you for this place to sleep. Thank you for not slamming the door in my face. Thank you for this oxygen.

“It sounds like you’re complaining,” a lady who helped me in high school said recently, after learning about the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that made me wish I could die without shirking my obligations by killing myself. The woman listed the things Harvard gave me: an address, a partner, a job. She wrote, “It WAS worth it!”

Each time I’m told I’m lucky, the message is the same: you don’t deserve this. We gave it to you, you ungrateful bitch, and we can take it away. So shut up. Stop whining. Wipe the spit off of your face and eat an oyster.

Even the prototypical success story grappled with the cost of victory. Early in his journey, the Velveteen Rabbit lay on a heap on the playroom floor while a washed-up rocking horse explained that becoming real was brutal. Most playthings could never endure it: either their sharp edges made them impossible to love or they fell apart before their transformation. The ones who made it became ragged. The rabbit asks, “Does it hurt?”

“Sometimes,” the mentor admits. He adds, “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt.”

Like the toys with missing buttons and bulging eyes and matted fur, my body remembers what I went through. I used to wonder what was wrong with me that I minded. Why, when asked what I expected, did I expect more? What gave me the right to think I deserved better?

When I declare, “It was worth it,” the reader will sigh with relief. I’ll absolve you of your guilt about all those kids sleeping in cars and on sofas who can only expect to be brutalized.

Inspired by the triumph of the human spirit, perhaps you’ll declare, “If she can do it, anyone can!”

Look at me. Listen: I am one-in-a-million. I am proof of the American dream. And when I wake up in the morning, I’m startled to be safe in my own bed. I rest my head on my husband’s shoulder. I will myself to relax. I bask in the three minutes of rest I get before the things I overcame come back to haunt me.

“In 2019, I’d been working on a memoir for four years, querying dozens of agents to no avail. I began writing the essay version of it and then came to the Community of Writers. That very intense week at Lake Tahoe boosted my confidence, giving me the courage to edit and send it out for publication. It ran in Longreads and a year later I sold Acceptance: A Memoir to Penguin Press, following the path the essay laid out for me.” Portions of the essay appeared in different form as “Self Portrait as a Human Interest Story” in Longreads, December 19, 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Emi Nietfeld.

Emi Nietfeld is the author of the memoir Acceptance, detailing her journey from foster care and homelessness to Harvard and Big Tech. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Rumpus, and Boulevard, as well as other publications, been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and noted in The Best American Essays. She lives in New York City with her family.

Emi Nietfeld is the author of the memoir Acceptance, detailing her journey from foster care and homelessness to Harvard and Big Tech. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Rumpus, and Boulevard, as well as other publications, been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and noted in The Best American Essays. She lives in New York City with her family.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

ESSAY

The People Who Read Me

by Susanne Pari

Years ago, the writer Molly Giles, who became my mentor and friend after we met at my first CoW conference, urged me to submit a chapter of my first novel-in-progress for a prize for writers of color. This was so long ago, the acronym POC wasn’t in the lexicon. I burst out laughing. “Have you not looked at me?” I said. “I’m as white as they come.” This did not dissuade her. I chalked it up to a certain sensibility (maybe ignorance?) I’d encountered in California, a “type” I was still trying to figure out since my arrival a few years earlier.

The identity box I always checked on forms was “Caucasian’.” This, because my father is from the actual Caucuses. Smack in the middle: Tabriz, Iran. Why Caucasian has been interchangeable with white in the U.S. is still not clear to me. The definition of “race” in America is a wobbly nonsensical concept that, in my opinion, takes up way too much time and not enough space. This is what happens when people think identity can be made sweet and simple when it is in fact, savory and complicated. I looked white, so I was white. My mother was a blue-eyed redhead from the Bronx. If I’d been browner, like many in my family, I may have thought differently. To put myself up for a POC prize would be, in my mind, gaming the system, and I was not a rule-breaker. Molly was simply misguided.

Except she wasn’t, at least not entirely.

I was what my Persian family called a double-veined girl; in English, that’s a “half-breed,” like the old Cher song. Half Iranian, half American. In those days, the hyphenated phraseology we now employ ad nauseam hadn’t been created. My identity was based on choices I made about whether I would do/think/believe in ‘the American way’ or in “the Iranian way’.” And they were never mixed, always intentionally bifurcated. But after the Islamic Revolution in 1979, our family was permanently exiled from Iran. I could no longer claim dual citizenship, and because I was born in the US, I couldn’t even claim I was an immigrant. I was an American, an identity that is so muddled and fluid, even Alexis de Tocqueville struggled to get it right.

During the Hostage Crisis, and later after 9/11, and later still after Trump, my light skin and eyes protected me from the discrimination that plagued so many, including my own son. It gave me the opportunity to call out the bigotry, explain and defend Iranians who had no association with the Islamic regime. I was fearlessly vocal about my politics, which was also often critical of US government actions. In this, I was what foreigners would label “very American.”

When I arrived at CoW that first time, in 1989, I knew no fiction writers and had never shown my timid chapters to anyone. I had no illusions about the work that was in store for me. And when, after the Conference, Molly invited me to join her workshop in San Francisco, where I met the writers who are now my closest friends, I understood that the road ahead was going to be long and not necessarily fruitful. It was the writing that mattered. I’d found my people.

What I didn’t expect was that those very writers—such close readers—would, over time, tell me who I was. It’s right there: in the subtext, in the deleted pages, in a character’s gestures, language, and relationships, in the stories we choose to tell: Iran, revolution, theocracy, fascism, female rebellion, patriarchy, family, exile, belonging. What Molly saw was my otherness, a thing I didn’t believe I had the right to feel. Identity in America is about appearance, the veneer: skin, voice, mannerism, costume. These are not on the page. On my page are the stories of a people whose birth country is often loathed and whose culture is misunderstood or dismissed. These truths would be borne out by my first novel’s unspectacular sales and by an arduous twenty-year journey to publish a second one.

I still have a hard time considering myself a person of color; my whiteness has offered me too many privileges in this America. But as my readers have shown me: my identity is complicated. And this seems more acceptable now than it did that first time around. Demographics? Maybe. Tolerance? Curiosity? Yes. But what I like to think is that they’re just catching up to Molly.

Susanne Pari is a novelist, book reviewer, essayist, and interviewer. Her first novel, The Fortune Catcher, told the story of a young woman caught up in the aftermath of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. Her second novel, In the Time of Our History, about the entangled lives of an Iranian-American family grappling with generational culture clashes, was published in January, 2023.

Susanne Pari is a novelist, book reviewer, essayist, and interviewer. Her first novel, The Fortune Catcher, told the story of a young woman caught up in the aftermath of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. Her second novel, In the Time of Our History, about the entangled lives of an Iranian-American family grappling with generational culture clashes, was published in January, 2023.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

MEMOIR

Playing the Long Game

by Christopher Upham

In 1974, I thought I could escape my time as a medic in Vietnam by roaring through Europe in a VW van for a year, but that dream died on a cold Norwegian lake, when I sank so impossibly low that I rowed out to throw myself into the dark, watery oblivion. Lying in the bottom of that boat, I felt like dying, then somehow felt a little better and returned to the world. The question then became: why? A little voice inside said: Write.

I decided that going to law school and having a family could save me, but when I lost my love and nearly failed out, I was forced into self-reflection, which somehow led me to Som Ranchan, a CSU Professor who taught graduate seminars on Durga Goddesses and J.D. Salinger’s work as Buddhist texts, which were inspiring and exotic. It was 1976, and to purge the war, I wrote a four-hundred-page, single-spaced typescript of autobiographical Vietnam stories. “These are not stories,” Som told me, “But a novel.”

After I finished law school, passed the California Bar, and worked at MacGillivray-Freeman Films in Laguna Beach, CA, I continued to rewrite A Theft of Fire. In 1983, I met Poet Bruce Weigl, and writer Gloria Emerson at a USC conference, Vietnam Reconsidered. Gloria encouraged me to submit my manuscript to acclaimed Simon and Schuster editor Alice Mayhew, who said my book “showed promise,” but “was not for them.”

I continued to work on A Theft of Fire, got married and moved to Berkeley. In 1987, my Vietnam novel was finally accepted for representation by Ben Camardi at Harold Matson Company, whose stable had included D.H. Lawrence, Malcom Lowry, and Flannery O’Connor. I was elated!

But after several years, A Theft of Fire did not sell. I kept writing, while also studying acting with Jean Shelton and Jim Cranna in San Francisco. Every year, I read (and rewrote) A Theft of Fire. My rule for that novel became if I didn’t see any improvement, I would shelve it. I never did.

In 1992, I returned to Vietnam as a guest of the Hanoi Writer’s Union with poet Bruce Weigl, to photograph a Vietnamese/English poetry translation project, which became the book, Poems From Captured Documents. After my marriage dissolved, I moved to San Francisco, and began acting in theater, features, television, commercials, and educational film. I continued to write novels, including A Theft of Fire, even during a bout of throat cancer, courtesy of Agent Orange, the gift that keeps giving.

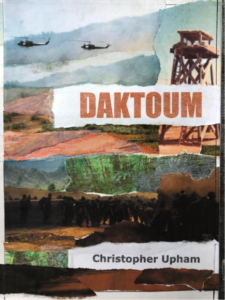

In 1998, I met Diana Fuller, and attended and then worked in the Community of Writers Screenwriting program, running an afternoon workshop that staged and filmed new writer’s scenes. With ongoing inspiration from the CoW, I continued rework my Vietnam novel, now called Daktoum, while writing plays, novels, and screenplays for myself, and for hire, as well as acting in a dozen professional stage productions and fifty films.

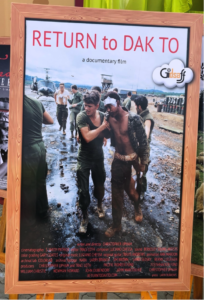

In 2004, I took four veteran comrades back to Vietnam for my documentary film, Return to Dak To, which played two dozen festivals world-wide, was distributed educationally, and screened at the National Gallery of Art. My documentary is a non-fiction exploration of the same terrain as my novel, Daktoum.

In 2006, my story, “Nothing to Crow About,” a story of mine was published in Veterans of War, Veterans of Peace, edited by Maxine Hong Kingston. In 2008, I met writer-publisher, Holly Payne, (2008 CW Screenwriting alum) who loved Daktoum. After engaging editors Maisie Cochran and Joaquin Lowe for two major rounds of editing, Holly agreed to publish Daktoum through her imprint, Skywriter Books. Unfortunately, Holly’s startup, Booxby, was funded by the National Science Foundation and, being a single mother, she had to close Skywriter. Disappointed, I was also deep into producing and directing my documentary and,

once again, Daktoum sank back into my dreams.

I continued working on Daktoum with a fierce determination and belief in the novel. When the pandemic hit, I was in Vietnam, filming my latest documentary, Soldier, Poet, Friend, about Bruce Weigl, translating Vietnamese poetry, the War, and the city of Hanoi.

After I moved from San Francisco to Santa Fe, New Mexico, I became determined to publish Daktoum before I die, so I formed an imprint, Cereus Press. I engaged Laura Duggan of Nicasio Press to shape, design, proof and guide me through the self-publication process. Daktoum is now available on Amazon in soft cover and e-book formats. I am currently sailing through the endless dark forests of social media promotion, finally a published author, with more novels to come.

Christopher Upham is a writer, filmmaker, photographer, and actor living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Return to Dak To, his prizewinning documentary about the long-term effects of combat, won prestigious Pacific Pioneer and Fleishhacker grants and is in educational release with Collective Eye Films. It centers on his experiences as a medic traveling back to Vietnam with four Army comrades. His Vietnam War novel on the same subject, Daktoum, was published in 2022. In addition to staffing the CoW Screenwriting Program, Upham has taught screenwriting at San Francisco State University, filmmaking at the San Francisco Film Society, and was Artist in Residence at MVLA Academy.

Christopher Upham is a writer, filmmaker, photographer, and actor living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Return to Dak To, his prizewinning documentary about the long-term effects of combat, won prestigious Pacific Pioneer and Fleishhacker grants and is in educational release with Collective Eye Films. It centers on his experiences as a medic traveling back to Vietnam with four Army comrades. His Vietnam War novel on the same subject, Daktoum, was published in 2022. In addition to staffing the CoW Screenwriting Program, Upham has taught screenwriting at San Francisco State University, filmmaking at the San Francisco Film Society, and was Artist in Residence at MVLA Academy.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

NOTES

Mirrors of Gigantic Shadows

by Matthew Zapruder

DREAMS

A poem is a dream made manifest in the world, not only for oneself but for others. In dreams begin responsibility. In poems responsibility continues. Like dreams, poems push back against that pressure of the real, which comes both from outside — the constant influx of opinions, information, news, content, that threatens to overwhelm — as well as from within. Writing poems makes a different space, and regardless of what the product of that writing is, the act of sitting down to make or read a poem in and of itself protects me, at least for a little while.

Nathaniel Hawthorne: “To write a dream, which shall resemble the real course of a dream, with all its inconsistency, its eccentricities and aimlessness — with nevertheless a leading idea running through the whole. Up to this old age of the world, no such thing has ever been written.” Apparently, he never read any poetry.

VOICES

Poets have always heard voices. For some reason we trust singers more than poets, when they say “the answer is blowing in the wind” or “I’m a radio,” or even when they tell us directly they are guided by voices.

Jack Spicer said he was a radio, tuned to alien messages. Emily Dickinson needed to be alone, in her room or the garden or walking her dog, Carlo, so she could hear them. James Tate sat quietly in his room, before his typewriter, waiting. Every night James Merrill and his partner David did the Ouija board, spirits of the dead came to them, and they wrote the great cosmological epic Changing Light at Sandover. Whitman stops doing anything, so he can become the sleepers, the darkness, everyone, and everything. All speaks through him. He says to Night, “Why should I be afraid to trust myself to you?”

“My quietness has a man in it,” writes Frank O’Hara. Adrienne Rich drives her internal Orpheus around in a black Rolls Royce, allowing it to learn to “walk backward against the wind/ on the wrong side of the mirror.” James Cagney (the poet from Oakland, not the actor) asks his mother what the lines in his palm mean, and she tells him he is an instrument of that which is the living force with in all of us, that his hand “takes the shape/ of the last thing spirit reaches for in its last darkness.”

This might be why poets are so often sheepishly astonished by what they make. We feel secretly guilty, like it wasn’t even really us. And it wasn’t. It was the collective knowledge of language, speaking through us. So when it’s time to try to write the next one, we can never remember how we did it. We know we need to make ourselves ready, but how? We write words that we don’t understand, wrote Percy Bysshe Shelley, and become “mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present.” This passivity makes poets oddly suited to the most dramatic moments in one’s own life, and in history. Our poems can reflect, in real time, that which no one in the middle of can truly understand.

QUESTIONS

When people think they don’t understand poetry, in my experience, the main problem is they are looking for the poem to be an answer. I like to think of the poem as a physical space, like a giant machine or a museum or a forest, into which one goes and emerges with better questions. Alejandra Pizarnik: “It is not true that poetry resolves enigmas. Nothing resolves enigmas. But to formulate them by way of the poem … is to unveil them, to disclose them. Only in this way can poetic inquiry become an answer: if we are willing to risk that the answer become a question.”

Poems can begin to clarify the questions that must honestly be asked if we are going to start to find real solutions. It seems to me that no matter how much information and how many facts and how much reason comes from the outside, nothing can change us if we do not change ourselves.

When life is most confusing and difficult, it most needs to be encountered directly. There are many ways to do this. I do it through poems. I have always learned something from writing poems: the poems are often far ahead of me, and help me see and begin to get past my fear. Sometimes they painfully collect that fear into nearly intolerable questions.

NEVERMORE

Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Philosophy of Composition” supposedly explains how he wrote “The Raven.” Here is how he describes deciding on nevermore:

“These points being settled, I next bethought me of the nature of my refrain. Since its application was to be repeatedly varied it was clear that the refrain itself must be brief, for there would have been an insurmountable difficulty in frequent variations of application in any sentence of length. In proportion to the brevity of the sentence would, of course, be the facility of the variation. This led me at once to a single word as the best refrain.

The question now arose as to the character of the word. Having made up my mind to a refrain, the division of the poem into stanzas was of course a corollary, the refrain forming the close to each stanza. That such a close, to have force, must be sonorous and susceptible of protracted emphasis, admitted no doubt, and these considerations inevitably led me to the long o as the most sonorous vowel in connection with r as the most producible consonant.

The sound of the refrain being thus determined, it became necessary to select a word embodying this sound, and at the same time in the fullest possible keeping with that melancholy which I had pre-determined as the tone of the poem. In such a search it would have been absolutely impossible to overlook the word “Nevermore.” In fact it was the very first which presented itself.”

That last sentence reveals precisely what happened: “nevermore” was the first word he thought of. The choice instinctive, the explanation retroactive. His explanation is so obviously reverse engineered that it almost seems like a joke.

Poe goes on to explain that he realized having a person say “nevermore” over and over again would be weird, so he decided it would have to be a “non-reasoning creature.” His first idea was a parrot. Person – parrot – raven. I can’t tell if I’m disappointed or relieved.

ENDINGS

Audre Lorde calls a poem “a bridge across our fears of what has never been before.” We can walk on it together. It is made out of the stuff of our collective knowledge. It is simultaneously private and public. It uncertainly crosses the distance between what I think and feel, and what you, mysterious reader, understand of me. It is an impossible act, doomed to failure. Yet it somehow crosses, and for a moment we feel alone together: simultaneously with others, and also deeply protected in our privacy and individuality. Anyone who has ever read and loved even a single poem knows this feeling.

Paul Valéry wrote that a poem is never finished, only abandoned. And yet, there is something about the final version of a poem. A click. Not as if great problems have been solved, which is of course impossible, but that they are newly visible in their clarity.

These notes were adapted from a forthcoming memoir, Story of a Poem, which you can preorder from Unnamed Press here.

Matthew Zapruder is the author of five collections of poetry, most recently Father’s Day (Copper Canyon, 2019), as well as Why Poetry (Ecco, 2017) and Story of a Poem (Unnamed, 2023). He is editor at large at Wave Books, where he edits contemporary poetry, prose, and translations. From 2016-17 he held the annually rotating position of Editor of the Poetry Column for the New York Times Magazine and was the Editor of Best American Poetry 2022. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing at Saint Mary’s College of California.

Matthew Zapruder is the author of five collections of poetry, most recently Father’s Day (Copper Canyon, 2019), as well as Why Poetry (Ecco, 2017) and Story of a Poem (Unnamed, 2023). He is editor at large at Wave Books, where he edits contemporary poetry, prose, and translations. From 2016-17 he held the annually rotating position of Editor of the Poetry Column for the New York Times Magazine and was the Editor of Best American Poetry 2022. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing at Saint Mary’s College of California.

Poetry Poetry Essay Staff Essay Lyrical Essay Tribute Essay Memoir Essay Memoir Notes Essay

ESSAY

The Writer

by Keenan Norris

In the interviews that I’ve done for my new book Chi Boy: Native Sons and Chicago Reckonings, I’ve been asked more than once what the most surprising discoveries of my research for the book were. I’ve told audiences about learning that America’s largest cities were founded by people of African descent (yep, Manhattan, Chicago, Los Angeles) and about the coloration of Chicago’s mid-twentieth century nighttime light-scape. What I haven’t told anyone until now is that in researching Chicago and the lives famous and unknown that traversed it, I found that Barack Obama at one time wanted to be a writer.

Yes, once upon a time the former POTUS tried to publish his creative writing in small literary venues and entertained dreams of making his way in the world as an ink-stained scribe. The story of Obama’s nascent literary dreams can teach us, or remind us, of a truth fundamental to the task, the toil and beauty of writing.

Barack Obama finished his bachelor’s degree in the spring of 1983. After a year working in financial services for Business International Corporation, where colleagues interpreted his dreamy mid-day reveries as indicative of a soul tempted more by literary ambition than a desire for a chief executive suite, the Columbia graduate found a job that he actually wanted, a community organizing gig in Chicago, the Developing Communities project. Impressed by his resume, the hirer, an experienced community activist named Jerry Kellman, telephoned Obama in New York. The questions Kellman asked were ones that Obama would field repeatedly in the coming years. Why Chicago? Why leave New York? Why leave his Hawaiian home, for that matter? Why serve as a community organizer in a place as gritty and downtrodden as the south side of Chicago? The work, after all, was, in the main, tedious, and frustrating, its excitements fleeting, its successes incremental, its failures continual. If Obama was so inspired by the city’s election of its first Black mayor, Harold Washington, why not work for Harold himself instead of doing community work at the distant periphery of power?