POETRY

Rethinking Bitcoin

by Major Jackson

What a word, an idea, “enough,” a notion

we should uphold more, enough, we who are led

by despots and presidents, and resultingly,

led by greed and a desire to hoard,

hoard air, hoard water, hoard systems

of exchange and currencies we cannot even

imagine, enough, born in some future, some days

ahead when we will think we have not enough,

and hopefully we will not be on our knees

having run out of enough natural resources like air,

like water, the brunt reality of all of our taking

and using up, enough, the answer is in proliferating

the virtues of “enough,” as in adequate,

as in satisfactory, as in sufficient, so that

we are not on the brink of degrading

our forests, of polluting our local ecologies,

our streams with sulfur and arsenic, enough,

such a lovely word, one we can drink

with morning coffee or tea, enough like a sharp

dosage of insulin for policymakers who like

the bald truth and data-driven facts, “enough”

like a cornerstone of a beautiful cathedral,

enough like a new religion, like a new friend,

a crush, enough like a wistful, blue sky

reflected in a puddle, a dreamy counter

to oil spills and chemical plants where local residents

are likely to ingest fumes and possibly

contract some disease; enough doesn’t

harm wildlife and is more than a theory

for the bookish, but a magnificent bead

in a string of elegant solutions:

Let’s say it, together, enough.

Major Jackson’s most recent books are The Absurd Man (Norton: 2020), Roll Deep (Norton: 2015), winner of the Vermont Book Award, and A Beat Beyond: The Selected Prose of Major Jackson (Michigan: 2022). His edited volumes include Best American Poetry 2019, Renga for Obama, and Library of America’s Countee Cullen: Collected Poems. Major Jackson lives in Nashville, Tennessee where he is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities and Director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Vanderbilt University. He serves as the Poetry Editor of The Harvard Review. For more information, please visit www.majorjackson.com.

Major Jackson’s most recent books are The Absurd Man (Norton: 2020), Roll Deep (Norton: 2015), winner of the Vermont Book Award, and A Beat Beyond: The Selected Prose of Major Jackson (Michigan: 2022). His edited volumes include Best American Poetry 2019, Renga for Obama, and Library of America’s Countee Cullen: Collected Poems. Major Jackson lives in Nashville, Tennessee where he is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities and Director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing at Vanderbilt University. He serves as the Poetry Editor of The Harvard Review. For more information, please visit www.majorjackson.com.

Poetry Poetry in Translation Essay Poetry Essay Tribute Poetry Nonfiction

POETRY in TRANSLATION

Di Freyd fun Yidishn Vort/The Joy of the Yiddish Word

by Daniel Kraft

To kick off my Substack newsletter of Yiddish poetry in translation earlier this year, I shared H Leivick’s poem, “Yiddish Poets,” translated from a 1932 edition. H Leivick (1888-1962) was the pen name of Leivick Halpern, who was for a time among the most beloved and respected Yiddish writers in the world.

His biography seems mythic, cinematic: after abandoning the orthodox Judaism of his upringing for revolutionary socialism, Leivick was sentenced to hard labor in Siberian exile. As the great scholars and translators Benjamin and Barbara Harshav write, “in 1906 he was arrested by the Tsarist police. He refused the services of a famous Russian defense lawyer and declared at his trial: ‘I will not defend myself. Everything I have done I did in full consciousness. I am a member of the Jewish revolutionary party, the Bund, and I will do everything in my power to overthrow the Tsarist autocracy, its bloody henchmen, and you as well.”

In 1913, Leivick’s revolutionary comrades managed to smuggle him out of Russia, and he lived the rest of his life in the United States, writing prolifically.

Wondrously, here is a recording of Leivick himself reciting this poem.

Yiddish Poets – H Leivick

When I consider us, Yiddish poets,

such grief engulfs me

that I want to scream to myself, and to beg,

and suddenly my words grow silent.

Our poems seem grotesque,

like ears of corn devoured by a swarm of locusts.

Our consolation is to find ourselves repulsive

and to slink across God’s earth like strange, alien guests!

The blood of our word on cold fingers,

from cold fingers to colder cement–

O laughable, shameful poet,

trapped in four shameful walls!

And when a neighbor comes to us,

up from the cellar or down from the attic,

he recognizes his mute tongue within us

and avoids our ceremonies.

And we, like childish and love-drunk knights,

like Don Quixote, past all bounds,

are the companions only of our trembling

and, lonely, tremble over every letter, every word.

Sometimes, like agitated cats

dragging disoriented kittens out of harm’s way,

we hold our poems in our teeth and drag them

by their necks through New York’s streets.

When I consider us, Yiddish poets,

such grief engulfs me that I want to scream

to someone near me, and to beg,

and suddenly my words grow silent.

Leivick is writing here about the particular marginalization of Yiddish poetry, but what he says of Yiddish poets could also be said of anyone: when we really consider ourselves, and our alienation from even the people closest to us, aren’t we all sometimes overwhelmed with grief? Who hasn’t now and then felt like an unwanted guest on earth?

Maybe I’m projecting here, and should just speak for myself. But I love this poem, partly because some aspect of myself which I would prefer to stifle or ignore identifies with Leivick’s isolation. For Leivick the poet is alone, unwanted, shunned by his neighbors, able to bear nothing but deformed fruits. Worst of all, perhaps: when he is most desperate to speak, to scream, to cry out for a different life, he cannot find even a single word.

Certainly I’ve felt all of this at various points in my life, and maybe you have too.

It sounds bleak, and it is, but it isn’t only that. There is also, I think, a kind of covert joy hidden beneath this vision of the Yiddish poet’s alienation. The fact that this poem exists is in itself a triumph, a paradoxical triumph, over the poet’s loneliness, and over the silences that stalk him. Leivick has found a way to write about, to communicate, his inexpressible grief. In describing his loneliness in verse he makes himself a little less alone; the poem transcends the isolation which the poem describes. Leivick’s art conquers his suffering, even as the art and the suffering persist side by side.

A question I have about this poem: in what ways is it “a consolation… to find ourselves repulsive?” I feel a psychological resonance there, but I can’t put my finger on it or articulate it. It’s not dissimilar, maybe, from the fact that Kafka understood his Metamorphosis to be a comedy.

Well, I promised myself that I would keep these little comments short, no more than a couple hundred words, so I’ll cut off my rambling here, but I’m grateful that you’ve read this far. It’s now about 90 years since this poem was first published, and I wanted to start my newsletter of Yiddish poetry in translation with it because I love that image of the poet as a stray cat dragging its kitten through New York City. The poet as an animal nurturing the poem in its vulnerability, protecting it through an inhospitable landscape. Keeping it safe.

And that’s what we’re doing with this newsletter, “Di Freyd fun Yidishn Vort/The Joy of the Yiddish Word,” bearing these Yiddish poems through this online city, and finding a way to keep them alive.

I send translations of a Yiddish poem out weekly, and always look forward to sharing. Feel free to subscribe at https://danielkraft.substack.com/

Daniel Kraft is a writer, translator, and educator living in Richmond, Virginia. He holds a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School, where he was a Harry Austryn Wolfson fellow in Jewish studies and a resident at the Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions. He has taught about Jewish history and culture in communities across the United States and in Poland, and his poems, essays, and translations of Hebrew and Yiddish appear or are forthcoming in publications including Image, Jewish Currents, and The Kenyon Review.

Daniel Kraft is a writer, translator, and educator living in Richmond, Virginia. He holds a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School, where he was a Harry Austryn Wolfson fellow in Jewish studies and a resident at the Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions. He has taught about Jewish history and culture in communities across the United States and in Poland, and his poems, essays, and translations of Hebrew and Yiddish appear or are forthcoming in publications including Image, Jewish Currents, and The Kenyon Review.

POETRY in TRANSLATION

The Story of Light

Written by Mohamed Metwalli

Translated from the Arabic by Mohamed Metwalli and Gretchen McCullough

For my father, Mohamed Metwalli Awad

Long ago a primitive man went out to his forest

He saw the moon above

Hit it with a stone and hurt its feelings

Since then the moon leaked light

From the opening in its dim glass

Despite that, some people still get lost on their way to the light

And seek a guide

Who would capture that speck of light in their souls

Tossing it before them

They chase after it

Some drink it in bars

Or disgorge it on the chests of their beloved

And others mold it into verse,

Or draw with it a lake and some trees with flocks of departing birds

Because of a gunshot in the air

That will never hit the moon now

Since it’s a holiday

And the fish in the lake revel in its light

The poet has lit a page or two

The drunk has guzzled half a bottle of light

And the lover has illuminated a whole bosom

Meanwhile, on the park bench

An old man was telling an attractive girl

The story of the first year of light!

He said that before great groups of stars

Were dimmed by what seemed to be a grip of divine inspiration

Noisy vagabonds crowded into the park,

With their gypsy music and flashy rags

They used to drink, talk politics

And disgorge light,

Birds perched safely on their shoulders.

The park was a grazing land for pastoral poets,

And lovers, unashamed of their nudity

While a film reel, in the background,

Displayed rare black and white footage

Of a few defunct moons

There was an owl high above

Whose eyes widened

With a light friendly to everyone

It kept hovering to purify their souls of rats and scared rabbits

Let’s say that’s how the story went!

In other words, the moon’s feelings were hurt

Because of a stray stone

So it leaked tears of light

On the empty park bench

On the eyes of the owl

On the rodents revealing their hideouts

On the escape of spirit from spiritual leaders

The moon’s feelings were hurt because of a stray stone.

It leaked light in tears.

A eulogy for everyone

A eulogy that comforted the son

Made him unafraid of death

And willing to be buried next to his father’s grave,

A eulogy that transformed the desire for breeding

Into a desire for a peaceful death.

A eulogy that promised everyone

To wake the dead from their forests

So they could make love

Unashamed Of their organs

Which keep disintegrating into dust

Unashamed of their skulls, that appeal to poets,

Which smile light during kisses,

Unashamed of their stuttering when female skeletons

Admire their rib cages,

Of their bouquet of radishes that look like roses

When presented before copulation as a primitive talisman,

Of the red snapper that was baked under the sand,

When the sun dried up its sea

The sun–the ally of diurnal people, Bedouins, farmers and shepherds–

Unashamed of the poetry of city people,

And cultural metropolises, an endangered species,

Unashamed of their tailbones and their stench!

They used to kiss their women and worship the moon

Since its feelings were hurt because of a stray stone.

It leaked, then cried light over their souls,

Sustaining them and their sons

Those who fear a peaceful death

Next to their fathers’ graves

In the ancient forest

Where the owl hovers with its eyes

The poet with his light of the page

And the fathers would rise, at night, from their graves

At the rarest patch of light

And teach their sons passion like the skeletons did

Wooing women with poetry, tickles, humor

And enlightened wineglasses

The moon’s feelings were hurt because of a stray stone

It leaked light in tears

To sustain everyone’s soul in the graveyard

Yet the fish ate each other in search of light,

Poets ate the poems of their peers

The trees, their birds

Park benches, their sitters

The hideouts, their rodents

The skeletons ate the skeletons

Then it was dark in the world

And we heard from our graves a voice like divine inspiration saying

That there was just one man left

Who looked exactly like the primitive man of the forest.

He was leaning on his cane,

Searching the earth for a stone,

While the moon was trembling with fear!

(2009)

……

N.B.: The forest and the park merge since they are the past and the present of the place.

From A Song on the Aegean Sea, by Mohamed Metwalli. Translated by Gretchen McCullough with the author, Published by Laertes Press, May 2022

Translated from the Arabic

FAREWELL

I say farewell to Izmir

To the Aegean Sea

To ships seeping their light

From afar

Silver and gold on the surface of dark waters

To the prostitutes, whose giggles

Still resonate

In the air, teeming with iodine

To the fisherman, battling a storm solo

Till his umbrella was buckled by the torrents

To the carcass of a dove

Struck by lightning in front of my very eyes

Devoured, later, by the raven and the seagull

To a roving musician who sang to us

From behind the restaurant glass

For two liras

To the geranium flowers on my balcony

That waxed lyrical when I watered them

To migrants flooding from behind the mountains

Dreaming of this city

Farewell, I say,

Farewell, beloved Izmir!

June 10, 2014

Meditation on Collaborative Translation, An Excerpt from the Introduction of A Song on the Aegean Sea, Published by Laertes Press, by Gretchen McCullough

We first started translating together shortly after we met in 2008. Mohamed thought my short stories, which were inspired by the Caireen district of Garden City, where I spent seven years of my life among a wide range of urban characters, would resonate with an Egyptian audience. He was the main translator of the collection, Three Stories from Cairo, published by Afaq Publishers, Cairo, in 2011. More comfortable translating from Arabic to English, I started translating his poems into English. Many of these translations eventually found a home in: British Banipal, Brooklyn Rail In Translation, Washington Square Review, and World Literature Today.

Typically, I translate cold without a dictionary to understand the general meaning. Then, I do another draft, using an Arabic-English dictionary if there are words I want to check. Mohamed and I then look at the draft, line by line and discuss the meaning in Arabic and try to negotiate a translation that balances meaning with a poetic sense. The other consideration is audience and linguistic register. Educated in British English, he may choose a word that is more commonly used in the U.K. If his audience is American, I will suggest words that are used more often in the United States. Another important issue would be the musicality of the word in English. Perhaps the word sounds flat or cliché in English. That is when we consult the thesaurus and the dictionary. If it doesn’t mean exactly what he wrote in Arabic, then we will go back to the Arabic-English dictionary. Besides assessing the words, the line breaks must make rhythmic sense in English. Translating poetry is like performing an acrobatic feat since Arabic syntax is completely different from English. If a single word or line break is wrong, it might feel stilted, or the word might land with a thud.

Quite simply, the literal translation of a poem will mangle a finely-honed text. Translation of poetry is time-consuming and cannot be mechanical in any way. It requires a similar artfulness to the care a poet takes when he/she writes a poem.

After graduating from Brown University in 1984, Gretchen McCullough taught English in Egypt, Turkey, and Japan. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Alabama and was awarded a teaching Fulbright to Syria from 1997-1999. Her stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in The Barcelona Review, Archipelago, Story South, Guernica, The Literary Review, The LA Review of Books, and on National Public Radio. Translations into English and Arabic with Mohamed Metwalli have been published in: Nizwa, Banipal, Brooklyn Rail in Translation, World Literature Today, and Washington Square Review. Her bilingual book of short stories in English and Arabic, Three Stories from Cairo, also translated with Mohamed Metwalli, was published in July 2011 by Afaq Publishers, Cairo. A collection of short stories about expatriate life in Cairo, Shahrazad’s Tooth, was published by Afaq as well in 2013. Her novel, Confessions of A Knight Errant, is forthcoming from Cune Press, Fall 2022. Currently, she teaches writing at the American University in Cairo.

After graduating from Brown University in 1984, Gretchen McCullough taught English in Egypt, Turkey, and Japan. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Alabama and was awarded a teaching Fulbright to Syria from 1997-1999. Her stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in The Barcelona Review, Archipelago, Story South, Guernica, The Literary Review, The LA Review of Books, and on National Public Radio. Translations into English and Arabic with Mohamed Metwalli have been published in: Nizwa, Banipal, Brooklyn Rail in Translation, World Literature Today, and Washington Square Review. Her bilingual book of short stories in English and Arabic, Three Stories from Cairo, also translated with Mohamed Metwalli, was published in July 2011 by Afaq Publishers, Cairo. A collection of short stories about expatriate life in Cairo, Shahrazad’s Tooth, was published by Afaq as well in 2013. Her novel, Confessions of A Knight Errant, is forthcoming from Cune Press, Fall 2022. Currently, she teaches writing at the American University in Cairo.

Mohamed Metwalli was recognized as a poet in the Arab world at a young age. Shortly after his degree in 1992 from the English department of Cairo University, his volume, Once Upon a Time, won the Yussef El-Khal prize for the best first collection by a poet in the Arab-speaking world, conferred by the Lebanese publishers, Riad El-Rayyes Books. He co-founded an independent literary magazine, El-Garad, in which his second book appeared: The Story the People Tell, Here, in the Harbor, and in 1997, he was selected to represent Egypt in the International Writers’ Program at the University of Iowa. The year after, he served as Poet-in-Residence at the University of Chicago. Metwalli compiled and co-edited Angry Voices:An Anthology of the Off-Beat New Egyptian Poets for the University of Arkansas Press in 2002. His third collection, The Lost Promenades, was published in 2010 by Al-Ketaba Al-Okhra, and A Song by the Aegean Sea came out in 2015 with Afaq Publishers. His poetry has been translated into French, German, and English, and his own translations have appeared widely in literary journals. In 2018 he was commissioned by the British Museum to render their conference publication, Asyut, Guardian City, into Arabic.

Poetry Poetry in Translation Essay Poetry Essay Tribute Poetry Nonfiction

STAFF ESSAY

All My Thoughts are Second Thoughts

by Karen Joy Fowler

I have spent the last few years working on a historical novel about the family of John Wilkes Booth. There is a wealth of material. I’ve looked at primary sources and secondary – letters, memoirs, unpublished manuscripts, testimonials, newspaper articles, theatrical reviews, playbills, and, of course, books written by better researchers than myself. I would guess that I spent roughly equal amounts of time on this novel reading and writing. I enjoyed the reading completely – it was full of wonderful surprises. There was a romance involving a lion tamer whose act displayed his well-muscled legs. Research simply cannot get better than that.

Readers tell me they like historical novels because it’s a painless way to learn history. I like them for the same (and many other) reasons. But a novel is a narrative. It’s been given shape, coherence, an agenda beyond a set of facts. Caveat lector.

I’m not talking here about the work of historians. I prefer to assume most of them are aware of the pitfalls and careful in their conclusions until I learn otherwise. I am talking instead about the project of historical fiction and how it makes me uncomfortable, even as I do it and love it.

I’ve always told readers of my first novel, Sarah Canary, that the most outlandish parts are the parts I didn’t make up. But also, that this doesn’t mean that those parts are true. Among the things I didn’t make up: a toddler taken in for some months by a motherly badger who did a better job raising the child than his human mother had done.

In the 1960s, I was part of the antiwar movement. I participated in any number of demonstrations, sit-ins and marches that were covered next day in the papers and on the news. Never once did I find coverage that didn’t contain significant errors. And I should know. I was an eye-witness to these events.

Of course, eye-witness accounts are notoriously unreliable.

#

When I was a child, I was told that my paternal grandfather had once wished to join one of those Sons of the Civil War clubs. In order to do so, he had to have an ancestor who’d been a soldier. Enter Tom Burke, conscript for the Union. Only there were two Tom Burkes, each equally likely as a progenitor. If our ancestor was the Tom Burke who died of malaria before seeing a single battle, Grandpa could join his club. If it was the Tom Burke who was shot for desertion, he couldn’t.

I didn’t hear this story often, only once or twice. I don’t remember how it ended, with Grandpa in the club or out. I only remember the details that interested me, mainly the two Tom Burkes.

And then, some years ago, my sister-in-law developed an interest in genealogy. Saliva swabs were collected. Research was done. She found that the first of our ancestors to immigrate from Ireland was a man named Patrick Burke. He arrived in the U.S. in the 1870s. If we ever had an ancestor named Tom, he most definitely wasn’t a soldier in the civil war.

I was shocked to learn that the earlier story had been a complete fabrication. I had questions, questions ultimately more interesting to me than whether Tom died of illness or execution.

Who made up the Tom Burkes? And why?

#

There is a fantasist in my family tree. S/he could have appeared in any generation after the war, telling any kind of story. A hundred years pass and no one is left to dispute it.

But I have three suspects closer to home.

- My grandfather.

He appears in the 1951-52 edition of The International Blue Book of World Notables, self-identified as an economist. He is said to be gathering materials for two books he is about to write. He does have the book titles; he’s gotten that far. It goes without saying that the books never materialized. I never saw this as dishonest so much as movingly aspirational. He was a man who had a lot of dreams.

My grandfather died sometime around my fifth birthday. I met him only once. He’d been a schoolteacher; my grandmother one of his pupils. They married, had three children, the third born with heart problems and a cleft palate. Then he deserted the family, leaving them in a state of such poverty my father’s cousin told me the children came to them every summer so that, for at least three months, they would have enough to eat.

After an absence of some duration, Grandpa did reappear. He’d decided to be a lawyer, tried and failed three times to pass the bar though my father insisted he was brilliant. He then suffered some sort of breakdown. By that time he was a member of the printer’s union, which funded a home into which he checked and never left. He was afraid if he gave up his bed, he wouldn’t get it back. I’m not sure how often he even saw his wife and children.

He didn’t like salads; he called them cow food.

And that is absolutely everything I know about my grandfather.

(How much of it is true?)

- My aunt Alvera.

Alvera contended that my father’s brother, Uncle Bob, the one with the heart problems, had a torrid affair with Georgia O’Keefe. She shared this gossip only after Bob had died, the soul of discretion. She claimed to have read letters documenting the affair. Unfortunately, they were so explicit, so, in fact, filthy, Alvera was forced to burn them without ever showing them to anyone else.

Alvera is an excellent suspect, though the Tom Burke story is a little modest to be hers. I feel the Tom Burke of Alvera’s invention would have more derring-do. Instead of malaria, I feel there would have been amputations.

Alvera often told me we were descended from Spanish royalty.

- Me.

I have only the vaguest recollection of having been told about Tom Burke.

At some point in my childhood, something someone said gave me the impression that my grandfather was a suave riverboat gambler and I spent a few years believing that until corrected. I am clearly capable of completely misunderstanding the situation.

In addition, I am what my loving mother always called a born storyteller. This actually means I am a born liar, but let’s go with her version. All of us shape our memories into narratives; we lie to ourselves all the time without knowing we’re doing so. I just turned professional.

And cleaned up my act. I’m a pretty reliable adult. I don’t really think it’s me.

But it could be.

#

Here is a story from the Booth family. Shortly after the birth of John Wilkes, on a cold and colicky night, his mother sat rocking him before the fire. On a whim, she asked to know what his fate would be. In answer, the fire shaped itself into an arm and sword. On the sword, the word country was written in letters of flame.

John’s sister Asia wrote a poem about this incident. She appears to believe wholeheartedly in it. But. Give me a break. This is a story someone made up. I wish they were all so easy to spot.

I think the fantasist this time must be John’s mother. An older son, Edwin, was the seventh child and born with a caul. The night Edwin arrived, meteor showers streaked the skies above Baltimore; stars fell from the heavens. There is outside corroboration for this – newspaper articles noted the remarkable celestial events. Maybe Mother was trying to correct the injustice of Edwin’s storied birth and John’s ordinary one. Maybe she didn’t want one son marked as special by the heavens and the other not.

One can only wonder about the effect on John of having been told his whole life that he was destined to be a fiery sword in defense of his country. Although a fiction, this story had consequence, became itself a part of American history. A lot of fictions have done so. Thanksgiving. The Maine. The Lost Cause. The Gulf of Tonkin. The Big Lie.

#

Here is another story intertwined with the Booths. It concerns the death of a young confederate soldier, a friend of John’s named Jesse Wharton. Jesse was shot by a prison guard while sitting in a window in a Union prison. I found two accounts of his death.

In one, he was peacefully reading his Bible, in fact, was meditating on his own mother’s favorite verse, when he was suddenly and inexplicably killed. This is a narrative trying too hard. Not content with the Bible itself, this fantasist has thrown Jesse’s sainted mother into the mix.

In the second, Jesse was leaning from the window, taunting the guard, shouting that the guard didn’t have the guts to shoot him. This is a narrative concocted to defend the indefensible, the killing of an unarmed prisoner of war.

I can’t know how Jesse died. But common sense tells me it was in neither of those ways.

#

America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.

Frederick Douglass

#

History is a powerful tool in understanding the present and creating the future. It wouldn’t be so contested if it weren’t so powerful.

I used to say that I didn’t believe in nonfiction at all. Once we understood the unreliability of memory; once we saw history as a form of the children’s game of telephone with its constant slippage during communication; once we acknowledged the human tendency toward story and also the proliferation of liars amongst us, this seemed the easiest way through. You are all just a pack of playing cards.

But I can’t do that now. Awash as we are in alternate facts, preposterous conspiracy theories, floods of carefully targeted misinformation, and threats of violence in support of lies, I can’t continue to suggest that it is all just up for grabs.

A sizable part of the American population is now demanding that children be taught a falsified history, a history that won’t make children uncomfortable or unpatriotic. I’ve read that among the things proposed as too sad for children to learn about are slavery, the genocide of the first peoples and, most recently, the internment of Japanese Americans.

The truth is under assault at school board meetings and all the way up the political ladder. We can’t defend the truth by arguing that there is no truth. So, in my 72nd year, I’ve made a U-turn.

Truth remains, as ever, messy and elusive; there is no way around that. As a historical novelist, the best I can do is proceed cautiously. In Booth I have done my inadequate best to tell a true story. The impossibility of distinguishing the true from the untrue is no excuse for not trying. Indeed, I believe now that the pursuit of the truth is an essential form of activism. Given that We cannot escape history. (Abraham Lincoln) – it’s imperative that we look critically and often suspiciously at our past, but all in service of working to get it right.

Karen Joy Fowler is a novelist and writer of short fiction. Her work ranges from literary to science fiction, from contemporary to historical. We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves won the 2013 PEN/Faulkner Award, the California Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Man Booker in 2014. Her novel Booth was published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons in 2022. She is currently sheltering at home in the beautiful city of Santa Cruz, California. www.karenjoyfowler.com

Karen Joy Fowler is a novelist and writer of short fiction. Her work ranges from literary to science fiction, from contemporary to historical. We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves won the 2013 PEN/Faulkner Award, the California Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Man Booker in 2014. Her novel Booth was published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons in 2022. She is currently sheltering at home in the beautiful city of Santa Cruz, California. www.karenjoyfowler.com

Poetry Poetry in Translation Essay Poetry Essay Tribute Poetry Nonfiction

POETRY and a VIDEO

On The Long Devotion

by Sholeh Wolpe

I sit at this kitchen table in Los Angeles and take account: There is my childhood house becoming smoke, friends scattered like storm-blown dandelion seeds, my mother tongue ripped blue from my throat.

See the man I used to call husband sinking into the twin lungs of an ice beast, a love murdered by his own pallid hands;

see vein shades of lovers who came and went, a homeland community in jail, my cousin’s husband graying on the run, my school principal and his wife hanging from beryl ropes.

Thatwechoosethecolor

of our loss, like a blue

sash draped across

mourners’ black. That

eyes follow blind

towards thecobaltmoon,

will slant us over and

down, crooked toward

mud on our graves.

چشم من آبی روی من آبی موی من آبی خون من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی آه من آبی دست من آبی خون من آبی جای من آبی زبان من آبی چشم من آبی روی من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی موی من آبی فکر من آبی روی من آبی موی من آبی خون من آبی چشم من آبی روح من آبی آه من آبی دست من آبی موی من آبی جای من آبی زبان من آبی چشم من آبی روی من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی خون من آبی روح من آبی روی من آبی موی من آبی خون من آبی فکر من آبی چشم من آبی آه من آبی دست من آبی زبان من آبی جای من آبی موی من آبی چشم من آبی روی من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی خون من آبی آه من آبی روی من آبی موی من آبی خون من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی چشم من آبی دست من آبی جای من آبی زبان من آبی چشم من آبی روی من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی موی من آبی خون من آبی روی من آبی چشم من آبی فکر من آبی خون من آبی موی من آبی روح من آبی آه من آبی دست من آبی زبان من آبی جای من آبی موی من آبی چشم من آبی روی من آبی فکر من آبی روح من آبی خون من آبی

(from Abacus of Loss, Chapter: Color of Loss, Bead 6)

Abacus of Loss is a memoir in verse in which I use prose, poetry, reportage and art to tell a story—that of my nomadic life. The book is constructed like an abacus: an ancient instrument with rods and beads used to calculate gains and losses.

Each chapter is a rod, and every story within it, a bead. The book is constructed to mimic the way memory functions, in other words, it is not chronological. Each chapter is a chunk of memory and memories are not always solid; they are both fuzzy and clear, abstract and concrete, literal and metaphoric, all at the same time.

In Abacus of Loss I invite the reader to step in and take the journey. It is my hope and intent that the reader recognizes our commonality and let the story become his or hers as well.

At the invitation of OGQ, I present to you a film that uses much of the text from chapter 2: This Coffin to further the experience of its journey.

(All drawings by Edvarda Braanaas created for Abacus of Loss)

I use film I have shot myself in various parts of the world, my own voice, and original music composed by Aida Shirazi and Sahba Motallebi as well as art created for the book by Norwegian artist Edvarda Braanaas to extend my scheme of prose/poetry/art storytelling.

I invite you to darken the room, close the door and join me in this 15-minute journey.

Sholeh Wolpe is an Iranian-American poet and playwright. Her most recent book, Abacus of Loss: A Memoir in Verse (Univ. of Arkansas Press) is hailed by Ilya Kaminsky as a book “that created its own genre—a thrill of lyric combined with the narrative spell.” She is the author or editor of more than a dozen books, several plays, and an oratorio and is currently a writer-in-residence at UCI. Sholeh lives in Los Angeles and Barcelona. For more information about her work visit her website: www.sholehwolpe.com.

Sholeh Wolpe is an Iranian-American poet and playwright. Her most recent book, Abacus of Loss: A Memoir in Verse (Univ. of Arkansas Press) is hailed by Ilya Kaminsky as a book “that created its own genre—a thrill of lyric combined with the narrative spell.” She is the author or editor of more than a dozen books, several plays, and an oratorio and is currently a writer-in-residence at UCI. Sholeh lives in Los Angeles and Barcelona. For more information about her work visit her website: www.sholehwolpe.com.STAFF ESSAY

Why I Couldn’t Quit

by Vanessa Hua

In the fall of 2009, I never knew when hives would descend upon me.

At dinner with friends, my lips would numb and swell, as if I’d been stung by wasps. I sipped ice water, trying to make the puffiness go away and hoping my friends wouldn’t notice.

Or, as I drifted off to sleep, the skin on my arms and back would begin to itch. My scratching raised angry red welts. I bought unscented laundry detergent and tubs of moisturizing cream, but nothing eased the stress after the rejection of my first novel.

The flare-ups would go on for years. Though I never received a formal medical diagnosis, I suspected that my book worries triggered the hives.

Over the summer, I’d received helpful feedback at the Community of Writers, incorporating revisions in the version that went out on submission. Though the novel came close to selling, it didn’t.

I was devastated, but I started other writing projects. Yet I always returned to my first attempt, unable to quit, driven by the same determination I had when I began to write fiction as a child.

Still, a part of me wondered if I’d made a huge mistake quitting my job in daily journalism. Some days, I wanted to chuck all my scrawled-over printouts into the recycling bin.

My immigrant Chinese parents were puzzled by my attempt at a career change. They’d sacrificed so much to give me and my siblings stability. But I couldn’t promise them that anything I tried would work out.

After the San Francisco literary magazine ZYZZYVA published the first chapter of my novel in 2011, my father was so pleased that he bought a two-year subscription; he hoped the editors would publish the rest of it serially.

He was ailing, and every day my novel went unsold was another day I feared he might never see it. He never did, in what remains one of my deepest regrets.

After he passed away, my husband, toddler twins and I left Southern California and moved in with my mother, returning to my childhood home in the San Francisco Bay Area. I was back in the very bedroom where I’d first dreamed of becoming an author.

I kept trying. I joined the Writers Grotto on a fellowship for emerging writers. In the lobby of this storied community workspace, framed book covers hung on the wall. At one of my first lunches, I felt like an impostor. Then a woman sitting next to me mentioned that she’d also written a book that hadn’t sold. Casual small talk, but a revelation for me: Every writer’s life had its ups and down.

Within three years, the year I turned 41, my short-story collection, Deceit and Other Possibilities would get published. That same year, my new agents strategized about getting me a two-book deal for A River of Stars and Forbidden City — the latter the one I’d written first, rejected but now resurrected.

While my novels were out on submission, I met up with a friend. Multiple editors were interested, and I was hopeful the stars would align, but my body remembered its past stress. As I recounted my previous publishing woes, my lips puffed up into Donald Duck proportions.

But the swelling faded as fast as it had come on — just in time for the huge grin I’d break into upon hearing my novels had sold.

A decade and a half after I began writing Forbidden City, it was published in May. While on book tour, I’ve had the great good fortune to see friends old and new; every event is a chance to thank the scores of people who encouraged me along the way.

I once joked with another aspiring writer that we didn’t need a life coach: We needed a psychic, someone who could tell us that every wrong turn would ultimately lead to book publication. Maybe then I wouldn’t break out in hives!

Of course, no one could promise us that. To take a leap, you have to accept that uncertainty, and try not to stew in self-doubt and envy.

Understanding that—more than publication itself—is perhaps what’s kept the hives at bay. I also realize that if that first novel had ended up shoved into a drawer, its scrapped pages still would have helped me become the writer I am now.

Vanessa Hua is an award-winning columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and the author of the bestselling A River of Stars and Forbidden City, as well as Deceit and Other Possibilities, winner of the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature and NYT Editors Pick. A National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, she has also received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and a Steinbeck Fellowship in Creative Writing, as well as honors from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Asian American Journalists Association.The daughter of Chinese immigrants, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.

Vanessa Hua is an award-winning columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and the author of the bestselling A River of Stars and Forbidden City, as well as Deceit and Other Possibilities, winner of the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature and NYT Editors Pick. A National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, she has also received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and a Steinbeck Fellowship in Creative Writing, as well as honors from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Asian American Journalists Association.The daughter of Chinese immigrants, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.

I’ve always been a little skeptical about gurus – you know, those long-bearded, white clad, saffron-robed, mostly men, who garner millions of followers, and somehow get rich while espousing the benefits of a non-material life. Or maybe I’m just jealous and annoyed because I’m an Indian immigrant who grew up in America and watched fellow hippies of my boomer generation get something from the land of my birth that was somehow unavailable to me.

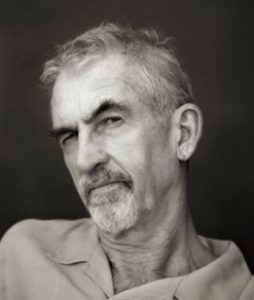

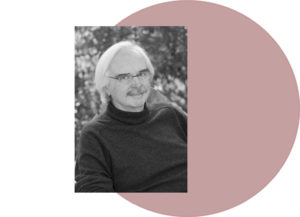

And then I found a guru. And became a believer. He didn’t have any of the accoutrements of those aforementioned spiritual teachers, except for the beard.

I first encountered my guru at Santa Monica Community College in a drab prefab classroom set up by Santa Monica College on their airport campus. This was in 1986. I had just earned an M.F.A. from UCLA Film School and was banging my head on the gates of the film industry. No one was going to let me, a woman of color, into that closed society. On the urging of a fellow film M.F.A., we signed up for Jim Krusoe’s Beginning Fiction class. Neither of us knew it, but we had just met our future. One semester later, we graduated to the Advanced Fiction class, the prefab became a regular classroom, and the classroom became our ashram for the next thirty-five years. Jim Krusoe became Guru Jim.

He was at the time a poet who had helped found Beyond Baroque, a center of literary rebeldom in the heart of Venice, CA, home to some of LA’s most iconic poets including Wanda Coleman, Bernard Cooper, Benjamin Weissman, Amy Gerstler, and Exene Cervenka. One day, early in my tenure in the class, he announced he was abandoning poetry to write fiction. He threw himself in the trenches with the rest of us and produced, over the next decades, a seriously impressive body of work including six novels: The Sleep Garden, Parsifal, Toward You, Girl Factory, Erased, and Iceland, (all from Tin House) and a collection of short stories entitled Blood Lake and Other Stories (BOA Editions), on top of his already published collections of poetry. As noted in a piece I wrote about his work in the Los Angeles Review of Books, his work is not for sissies. It illuminates the uncomfortable places in the human soul with dark humor, and best of all with deep understanding of what it means to live in a world that has become incomprehensible.

For thirty-five years he opened the doors of writing to a highly motley crew of ambitious writers. No one was turned away; everyone was invited back. Krusoe maintained an open-door policy (that Santa Monica College mostly turned a blind eye to) that brought writers from all over Los Angeles, and a legendary literary community was created. “So what are you reading?” was the question Krusoe asked as everyone settled behind school desks arranged into a circle. For the next half-hour students shared what they were reading and their thoughts on the work. When one student proclaimed he had read War and Peace Krusoe replied with a sly grin “Did you send away for the sticker?” There’s a sticker for that?” the student asked. Rarely was there a book or an author that Krusoe had not read. The idea that you could aspire to be a writer without reading was an insult to him. For the rest of the class, we listened to our peers read from short stories, novels and memoir chapters. We were instructed by Krusoe to listen with respect and kindness, and when critiquing to always start with what we found positive in the work. This was one seriously generous guru. But what we waited for were his comments and critique. His insight into writing went far beyond the conventional tropes like “show, don’t tell.” He might jump up to the blackboard and sketch out a diagram of the how the story went cleanly from Point A to Point B when it might have been much more interesting if it had detoured to Point C, saying, “The danger of knowing where you’re going is that you take shortcuts and hurry to get there.”

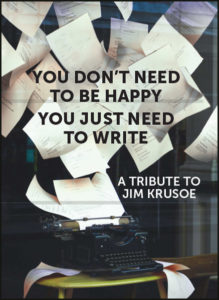

I started taking notes, writing down some of his gems: “write a dream, lose a reader” or “all fiction is desire then obstacles.” When I heard him ponder retirement in 2019, I felt a jolt of panic, then a call to action. I guessed others must have kept notes too, and I put out a call to former and current students to send me five things they had learned from him. I received an outpouring of responses. “Write a bad story,” he told one student. Given permission to fail, she went on to the write her best story. Another wrote in a testimonial: “When I first stepped into your creative writing classroom you didn’t know that I came from a background where reading and writing had not been valued… you didn’t know how difficult it was for me to return to community college again because of how dumb and useless and awkward I felt. You introduced me to a world of writing and talented people and treated me in a way that made me feel like I was home. You made me feel safe…What I am trying to say is that you saved my life on that first day of class and you probably didn’t even know it.” This was Guru Jim’s magic—his belief in all our voices was as close to a miracle as I’ve experienced. Eighty writers responded to my call. The writing advice flowed organically from the experiences recorded in moving testimonials. Natalie Baszile remembered “start with the spring already compressed,” and how Krusoe’s one suggestion to elevate the dramatic tension in her novel changed the whole tenor of Queen Sugar. Dylan Landis remembered Krusoe saying “Every story must have a basement.” One of my favorites was “bad art has no mystery in it, unlike the universe.”

There is so much more. Published writers (some of them also alums of Community of Writers) such as Natalie Baszile, Dylan Landis, Andrew Tonkovich, Lisa Alvarez, Lee Montgomery, Steve De Jarnatt, Mary Otis, Janice Shapiro, Ana Reyes, and many others contributed what they had learned from Krusoe. Thus, You Don’t Need To Be Happy, You Just Need To Write, A Tribute to Jim Krusoe was born. It is both a tribute to an extraordinary teacher, and a craft manual that will spark any writer to think differently about their work, to strengthen and deepen it. It will rank up there along with Oakley Hall’s The Art and Craft of Novel Writing, Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and the Story, and Ron Carlson’s Ron Carlson Writes a Story.

The pandemic and the transition to Zoom hastened Krusoe’s decision to retire. The class came to an abrupt end in March 2020 and brought the close of a bright era in the LA literary community. Fortunately, the book is here — Krusoe’s voice on every page — and with it one is guaranteed to find a way to get fruitfully lost in the wilderness of the writing life, a life for which there is now a guru.

To purchase a copy of the book: www.mononawali.com

Born in Benares, India, Monona Wali is an award-winning novelist and filmmaker. She lives in Los Angeles where she teaches writing and literature at Santa Monica College. Her debut novel, My Blue Skin Lover, won the 2015 Independent Book Publishers Gold award for multicultural fiction. It is soon to be released as an audiobook featuring Grammy award winner Neela Vaswani as the narrator. Her stories and essays have been published in the Santa Monica Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and many other journals. She is an alum of Hedgebrook, Breadloaf, and the Community of Writers. Her film Grey Area is included in the LA Rebellion, curated by the UCLA Film and Television Archives to highlight groundbreaking work done by BIPOC filmmakers in the 70’s and 80’s. www.mononawali.com.

Born in Benares, India, Monona Wali is an award-winning novelist and filmmaker. She lives in Los Angeles where she teaches writing and literature at Santa Monica College. Her debut novel, My Blue Skin Lover, won the 2015 Independent Book Publishers Gold award for multicultural fiction. It is soon to be released as an audiobook featuring Grammy award winner Neela Vaswani as the narrator. Her stories and essays have been published in the Santa Monica Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and many other journals. She is an alum of Hedgebrook, Breadloaf, and the Community of Writers. Her film Grey Area is included in the LA Rebellion, curated by the UCLA Film and Television Archives to highlight groundbreaking work done by BIPOC filmmakers in the 70’s and 80’s. www.mononawali.com.

Poetry Poetry in Translation Essay Poetry Essay Tribute Poetry Nonfiction

POETRY

SONNET WITH ICE HOCKEY AND NIGHT GOGGLES

by Robert Thomas

Who are you with now? Maybe some jarhead

or SEAL, the guy who slid down a thick rope

from a Black Hawk one moonless night and shot

bin Laden. You love when he wears the night

goggles. Or maybe Mario Lemieux,

six feet four inches of hockey genius,

Montreal grace and Pittsburgh grit. Isn’t

what I’m afraid of that you’re with my dad,

saluting the dashing Dr. Thomas,

Navy captain and surgeon, authorized

to operate on a nuclear sub

in case of World War III? I can see you:

brave nurse, longing to hand him his scalpel,

how flawlessly his hands open the flesh.

SONNET WITH LOBSTER AND PRIEST

Why is it the rule, not the exception,

for a lobster and a missionary

to fall in love, or a king and a cork?

Nothing can come of it. Evolution,

as Whitman said of death, must be different

and luckier than we thought. The priest learns

to swim and take delight in his body,

the lobster to pray on its pilgrimage

down the open road of the sea. The cork

comes to fathom the majestic power

of its silence. The god in us does not

want what we want. The king learns the patience

to wait in the cellar till the flavors

of cedar and violet bloom in his wine.

Robert Thomas’s novella Bridge (BOA Editions) received the PEN Center USA Literary Award for Fiction. His first book, Door to Door, was selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the Poets Out Loud Prize and published by Fordham. His second collection, Dragging the Lake, was published by Carnegie Mellon, also publishing his forthcoming book Sonnets with Two Torches and One Cliff. He has received an NEA fellowship and a Pushcart Prize, and lives with his wife in Oakland, California. He attended the Community of Writers in 1988(!).

Robert Thomas’s novella Bridge (BOA Editions) received the PEN Center USA Literary Award for Fiction. His first book, Door to Door, was selected by Yusef Komunyakaa for the Poets Out Loud Prize and published by Fordham. His second collection, Dragging the Lake, was published by Carnegie Mellon, also publishing his forthcoming book Sonnets with Two Torches and One Cliff. He has received an NEA fellowship and a Pushcart Prize, and lives with his wife in Oakland, California. He attended the Community of Writers in 1988(!).

Poetry Poetry in Translation Essay Poetry Essay Tribute Poetry Nonfiction

NONFICTION

Finding the Milky Way

by Ramona Reeves

During the first year of the pandemic, my wife and I assembled 1,000-piece puzzles, grew squash, and nursed tomatoes. We fixated on the latest Covid information and spoke to neighbors across driveways. I was privileged to work from home and tried not to complain but sometimes did. What I did not do that year was focus much on the collection of linked stories I’d written and sent to several agents the year before. The idea that the manuscript could go on to win a prize was as alien to me as a black hole.

I had tried to sell my collection as a novel told in stories because that’s what I thought it was. Agents indirectly told me otherwise. Some made lovely comments about the writing but expressed confusion about the pacing or character throughlines. As 2020 arrived, I accepted I’d written a linked short story collection and not a novel told in stories. True, the collection contained an arc of sorts, but it did not pulse with the continuous progression of many novels.

The earliest stories from the manuscript had begun in the before times, in a creative writing course that was part of the MFA program I’d begun at forty-three. After finishing the program in 2010, I put the stories aside for about three years. When I returned to them, I spent two years drafting and choosing the ones that would comprise the book and another two years revising them.

During those years of drafting and revising, I realized one advantage to writing connected stories was that they invited me to imagine characters’ lives beyond single narratives. I could peer across the landscapes of their lives and choose the stories to tell. The spaces between stories called to me as well. I envisioned those spaces filtering unspoken language and making room for readers’ imaginations, too.

But as the first year of the pandemic wore on, I made the painstaking decision to let the collection sit and focus my attention elsewhere. I found solace in a novel and returned to the collection only sporadically, sometimes to revise a story or a scene. At the behest of my wife and friends, I sent the manuscript to a smattering of contests.

Honestly, it felt both good and difficult to work on another project. Not because of my decision to let the collection sit but because of the pandemic, racial inequities and political turmoil swirling around me. Sometimes I cried and consoled friends. Sometimes I ate and picked tomatoes. But more often than not, I wrote, mostly from a belief that writing and art mattered, that writing and art could heal.

One major change I did make to the collection in 2020 was to re-order it. A group of writing friends I’d met at Community of Writers suggested playing around with the arrangement, and I took their advice. I mention these friends because writers I’ve met along the way have been a critical part of my growth and sanity. And I hope I’ve been a part of theirs as well.

In early 2021, I asked a trusted reader to take a look at the manuscript in its new order. A few months later, she returned it with a handful of copy edits and one major suggestion. Change the title. Upwardly Mobile and Other Stories—the collection is set in Mobile, Alabama—felt incongruent to her. Although the collection deals with themes related to class, her suggestion immediately resonated. I changed the title to one found in the collection, a title whose irony seemed to fit not only the book but the state of the world around me: It Falls Gently Around and Other Stories.

Shortly afterward, I submitted the manuscript to the Drue Heinz Literature Prize. What I should say is that I almost didn’t submit. I’d read two previous winners’ collections, including one by Caroline Kim, whom I met at the Community of Writers the year I attended. Although the contest had no submission fee and I met the eligibility requirements, I hesitated to enter.

The truth is, I was afraid of more rejection, afraid of sending my work into the abyss, afraid the work might not be up to par, afraid I might not be up to par. I was afraid I was too old, too queer, and too thick around the waist to be read seriously.

Another voice reminded me that my body, though imperfect, had carried me through numerous hard times and past many obstacles. I thankfully listened to the second voice and submitted to the contest in June 2021. Mind you, except for my wife, I didn’t tell another soul about my submission, but submissions are like that sometimes, quiet audacious acts.

Months later, when the publisher of the Drue Heinz prize phoned me, I didn’t answer. Robo call, I thought. They emailed instead, and when I learned my collection had been chosen by the contest judge, Elizabeth Graver, I was utterly shocked, beyond thrilled, and certain I was being punked. But there it was, a surprise like driving out into West Texas after dark and seeing the magnificent Milky Way, unencumbered by artificial light.

Life and writing have taught me that everything can change in a moment. Yet the spaces between those moments can feel like the most stuck places on the planet. I’d felt stuck for years but kept writing. And I’ll probably feel stuck again in some place or space, some between part of life, but to me, that’s narrative structure in real-time.

Sometimes I wonder if we tell stories to remind us not only of where we’ve been and might go but also to remind us about the moments lurking beyond our imaginations. Like the story I now tell that once seemed beyond mine, how in my fifties and married to a woman and too fond of sweets, I won a contest that published my debut work of fiction.

Ramona Reeves is the winner of the 2022 Drue Heinz Literature Prize for her linked short story collection It Falls Gently All Around and Other Stories (available October 4, 2022). Her fiction and essays have appeared in Bayou Magazine, New South, The Southampton Review, Superstition Review, Texas Highways and others. Originally from Alabama, she now lives with her wife in Texas.

Ramona Reeves is the winner of the 2022 Drue Heinz Literature Prize for her linked short story collection It Falls Gently All Around and Other Stories (available October 4, 2022). Her fiction and essays have appeared in Bayou Magazine, New South, The Southampton Review, Superstition Review, Texas Highways and others. Originally from Alabama, she now lives with her wife in Texas.

Poetry Poetry in Translation Essay Poetry Essay Tribute Poetry Nonfiction

Editor’s Note

One takes affirmation or encouragement where and whenever it appears. Call it recognition, solidarity, or something like light. Reading a recent New York Review of Books, I opened the back pages to observe, celebrate, recognize two Community of Writers pals, mentors. On the port side of the magazine was a NYRB Classics ad for Generations: A Memoir by our own Lucille Clifton (introduction by Tracy K. Smith) and on the starboard, a NYRB classics advertisement for Butcher’s Crossing by John Williams, with introduction by Michelle Latiolais. This felt at least a little important, gently thrilling, and certainly esteeming of my, and our choices of friends and literary comrades, and not only did I bask for a moment before reading excellent, long reviews and thought pieces but then wandered in my mind to Tracy K. Smith’s anthology (with John Freeman) There’s a Revolution Outside, My Love: Letters from a Crisis (2021) which includes contributions from — that’s right! — Community of Writers staffers Oscar Villalon, Hector Tobar, Camille T. Dungy, Greg Pardlo, and Major Jackson. Alas, Michelle, Oscar, and Hector did not make it to the Valley this year. Yet here, and there, they are.

Then my mind drifted further to Steve Almond’s recent book on the John Williams novel William Stoner and the Battle for the Inner Life as my body took over, walking me over to my bookshelf to pull out of a couple of the above titles. I was free associating — mental aerobics! — and it was all actually free except for the cost of my subscription to the estimable and urgently necessary NYRB, and I was associating with members and friends of the Community of Writers.

I trust you’ll divine my clumsy theme here, as we offer the latest issue of the OGQ, where you will recognize, read and associate, freely, vigorously with some of our own who’ve generously contributed their work in the spirit of solidarity and that particular variety of self-conscious “confirmation bias” about community upon which I rely a lot lately, and which perhaps also buoys your spirits. There’s poetry here, and poetry in translation, an amazing video performance, essays about writing and publishing, a tribute to a staff writer, and more poetry! In this issue you might find yourself, through others, as we celebrate our shared achievements here and in so many ways.

Editor, OGQ

ABOUT THE OGQ

Omnium Gatherum Quarterly (OGQ) is an invitational online quarterly magazine of prose and poetry, founded in 2019 as part of the 50th Anniversary of the Community of Writers. OGQ seeks to feature works first written in, found during, or inspired by the week in the valley. Only work selected from our alums and teaching staff will appear here. Conceived and edited by Andrew Tonkovich. Submissions will not be considered.