EDITOR’S NOTE

Thinking of You

By Andrew Tonkovich

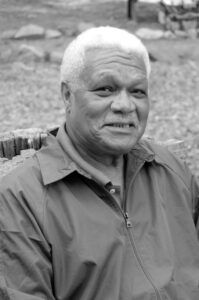

We’re grateful to participants and staff of both the Writers Workshops and Poetry Program, and especially alums who returned to the Valley this year to read their work. And to ZYZZYVA editor-in-chief Oscar Villalon, whose Welcome address to the writers’ program leads off our newest Omnium Gatherum Quarterly. His celebratory remarks saluting the late Alan Cheuse make the OGQ’s tributes to the late Al Young even more resonant as Alan and Al were dear friends. Readers might donate to the Al Young Scholarship HERE. Al’s biography deserves its own issue, a book, a many-stanza’d blues, but for now we include appreciations from Persis Karim, Lisa Alvarez, and Barbara Tannenbaum with photos by Barbara Hall and Brett Hall Jones.

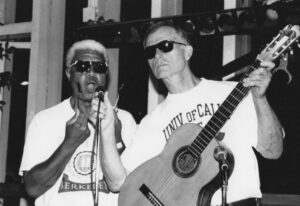

Al and James Houston played and sang in the Writers Workshop Follies as the Granite Chief Quintet, performing a clever, fun ditty called “White Man’s Blues,” with Jim on ukelele and Al on credit card. A highlight of every conference, the two sincere crooners hammed it up with intentionality and generosity.

The summer 2023 issue also features a long-form collective poem curated by Poetry participant Frank Karioris, a first-time real-time collaborative on-site experiment in group engagement with this terrific form. Thanks, Frank. Read his intro first to learn the rules of “renga.”

We also feature essays from Hilary Zaid, Jasmin Hakes, Rita Chang-Eppig, and Stephanie Austin, and a dispatch from the picket line by multi-talented — and striking! — writer Andrew Nicholls. Because our community is engaged in so many creative ways, we share a recipe (!) by poet, writer, and food culture blogger Natasha Saje. Celebrate the holidays early or save for later.

Finally, this issue is dedicated to the memory of writer, CoW participant, and friend Laurel Leigh (1963-2023).

Andrew Tonkovich

Editor, OGQ

OPENING TALK 2023

I Belong Here and So Do You

By Oscar Villalon

I first ascended to Olympic Village in my twenties. I was the deputy book editor at the San Francisco Chronicle and something of a yearling. Though I was already an experienced newspaperman, my understanding of literature was strictly relegated to what I copiously read—novels, story collections, and nonfiction, of course, but also the New York Review of Books, Harper’s, The New Yorker—and to the occasional attendance of a conversation between authors at the Herbst Theater. My experience of literature was strictly that of the reader, which as you know, can be a plush sinecure, one in which the eyebrow-raising toil that produced the luxuries stacked by your bed and sofa need not to be in the fore of your mind.

I had been asked to be on a book reviewing panel of two with the late great Alan Cheuse, whom I knew of from his regular broadcast appearances as book critic for National Public Radio. I wasn’t aware then that Alan, with whom I would later become friends, was an author and a fine fiction writer, too. (Indeed, I was not aware of many things then, but such is youth.) I would be staying for a couple of evenings during the middle of the week, and I had no idea what to expect. It was my first time at a writing conference, and my first time coming to the Sierras since the end of the fall semester my freshman year in college. Two high-school friends of mine and I drove from San Diego to Northern California in a scruffy Honda and toured the place on the cheap, surviving off of pull-top cans of Vienna sausages and a plastic sack of the pork tamales my father made for Christmas. We reserved a canvas tent for the night in Yosemite and slept a few feet from the snow, happily miserable in our unsuitable sleeping bags, and at one point even went skiing. Or I should say they skied. I spent the day in an air-hangar of a lodge, nursing a single paper cup of hot chocolate and reading The Death of Artemio Cruz. I was annoyed when my friends had finally exhausted themselves and came to find me. I had come so close to finishing the novel and had been in something of a hallucinatory reverie.

Being a single and unburdened deputy book editor, I was wealthy with hours, so I spent them. I came up to the Community of Writers on the train, reading all the way until we got past Auburn. From just outside the town where Ambrose Bierce convalesced, I marveled from my window at the thrash and the gush of the American River, as well as at the impressive tunnels belting the mountains as the Amtrak rolled its way into Truckee. I arrived carrying a small duffel bag, half of which was stuffed with my Navy peacoat, my proudest possession. I had been told it gets very cold at night in the summer, so the coat came with me, and still it wasn’t enough. Walking back to my lodgings under the moonlight, the chill was sharp enough at times to make me suck in my breath. For those of you who packed too lightly, this piece of knowledge may be alarming. All I can say is, wear layers if you’re going out at night.

In my memory, Olympic Village was something of a ghost town then, nothing like the warren of shops and bars and eateries you see now. There was only an attenuated grocery store within walking distance, though rides to anywhere were easy to cadge. The sprinkling of people one saw were either staff or participants, or forlorn employees from around the Village. The setting was secluded. And majestic. The two days and evenings I recall in montage, flickering scenes of egalitarianism and good will, of being immersed in what I suppose you could describe as cheery monasticism or even golden adolescence, wherein everybody you meet could and maybe should be your friend because you undoubtedly care deeply about the same important things, namely reading and writing and ideas.

My panel with Alan was casual and unguarded to the point of familial intimacy. By this time, I had already done a few literary panels, especially those on the necessity and practice of book reviews, and nearly always, during the Q&A, somebody whose back had been rigid the entire time, would ask me, Why didn’t you review such and such book? Or why aren’t you reviewing romance novels? and more often than not the person asking that was a romance novel writer or the author of such and such book. So you go into these things feeling tense in your shoulders and neck, is what I’m saying. But the audience here just lounged, draped across their chairs or wherever they chose to sit; to behold their collective ease was a balm. In fact, there was much lounging everywhere, as I recall: on the decks, on the grass, at kitchen counters. But it was lounging as a state of communion, what you would expect to find in a locker room after a demanding practice, teammates plopped next to each other, knowing they each gave their all and taking heart in that. My first time here, I hadn’t sat in a morning workshop or much less led one. But what I was seeing was the afterglow from the dedication and effort applied at the workshops earlier in the day.

And then my time was up. I was dropped off at the train station in Truckee, where after an insultingly long wait, the Amtrak came and returned me to the lowlands.

Before that first trip, I had known who my people were. Having worked at newspapers from the 10 th grade through the 12th, and then all five years of college, and then from college straight on to community dailies and, finally, the Chronicle, I knew where I belonged—with newspaper people, those ink-stained, dark hearted wretches, God bless them. And being around these writers, both participants and staff, eating and talking and hanging out with them, if even for just a couple of days, was enough for me to know undoubtedly one thing: these were not newspaper people. Sure, there were similarities. My cohort worked just as hard at their craft. And huddled in a group around a table at a bar, after a long day of getting the paper out, there could be the same expression of repose and satisfaction. But very few of us read. I mean, how did I even get my job? Because my boss noticed that I always had a book on my cubicle desk. Hey, you’re a reader, she said. You interested in this deputy book editor job? And before that happened, one of my fellow copy editors—a thoughtful and well-educated person–asked me how it was possible I read so many books given all the reading we had to do at work. This, I said all too bluntly, pointing to a proof, is not real writing. We’ve been eating Cheetos, I said. I need nourishment.

So you go out of town for a couple of days, meet people you might otherwise have never met, take in some things you would have otherwise have never experienced , and your mind stealthily

recalibrates. You think you know what you know, and if you would have asked me at the time, what is your vocation? What are you all about? I wouldn’t have given you the answer I would give you now. Just the same, long before I could articulate it, the Community of Writers—the writing and literary community at large—these were my people.

What does that even mean, though? And what does that mean in the context of this week, this Brigadoon tucked into the Sierras? For one, it means being part of a community that derives meaning and exaltation from literature itself. We understand the power of the written word, how it can crack us open and allow us to see what we previously hadn’t, how it gives us a vocabulary for understanding as best as we can during our too short of a time upon the earth such things as love and its lack, the unfathomableness of family and friends, implacable death and the mystery of being. In a society that generally devalues literature even as it starves for what those things can provide, having this time together, away from all the demands and obligations that would normally intrude, is exhilarating. This will be the rare air you will be breathing—barring any visible signs of encroaching wildfires. And though our backgrounds are varied and informed by unignorable quotidian realities, we are all compatriots of a place that is borderless and timeless—the republic of letters. As such, I receive you all in good faith, my fellow travelers. Yes, you are here to learn from workshop leaders, panelists, guest authors, and others, but it can’t be helped that we also learn from participants and participants learn from each other. That is what happens when you are part of a community. This is the give and take of camaraderie.

Another special thing about being with each other this week is knowing all of us share a healthy respect and an appreciation of the labor that goes into writing. Recall what I said earlier about the sweet privilege of the reader. They’re like a flip-flop-wearing guest at an all-inclusive resort, ordering round after round of Martin Amises, availing themselves of the buffet, piling on their plate Joy Williams, Juan Rulfo, and James Baldwin, and taking the leftovers back to their partial ocean view room with the lanai terrace. Such bliss! We all recognize this sumptuous state of being because we are just as much readers as we are writers. Or at least we should be. I have heard of the phenomenon of people who want to write but can’t be bothered to read. I like to believe this is apocryphal. I have yet to encounter such a creature in the wild, but if I ever did, and if I wasn’t choking apoplectically, I would tell them this is like wanting to be a good musician but having no time to listen to, you know, songs. And there’s the key word: “good.” Reading is a form of practice; it’s how you develop an ear for what works and doesn’t. And the like the man said, you play how you practice. But I digress.

The work of writing can frustrate, confound, exasperate—the sentences do not do what we want them to, which is all the more galling should you believe you’ve finally figured out what it was you were trying to say. Getting it right can take a considerable amount of unacknowledged effort, of invisible dedication, and yet we carve out the solitude we need when and where we can because it matters that we get it right. I’m reminded of something the British author and the Shakespeare of comic book writers Alan Moore said. Moore, if I have this correct, identifies as a Wiccan, and as such was talking about magick and spells. People think sorcery is the stuff of hidden realms, of the truly occult, rarely beheld, but as Moore points out, what do you think writing is? He explains how in novels and stories and poems and essays every word, every sentence must be constructed just so, as one would do with an incantation, for the magick—for the writing–to work. Again, we all know literature’s power to affect us in a way that expands our intellect and our spirit, but there’s also the way in which it can mesmerize as I was mesmerized by Carlos Fuentes’ novel all those decades ago. How deeply and effectively a narrative can do that is what we’re all trying to figure out here and then summon in our own work. It’s no small thing to be among people who know exactly what an undertaking that entails. It’s heartening, is what it is.

So when you’re in workshop, and fresh eyes are reading pieces you’ve been too close to for too long, and things are being pointed out that you perhaps hadn’t considered, do not lose heart. It just means you’re getting that much closer to where you need to be with that particular writing. We all wait to hear from trusted readers and editors, to receive the suggested notes that could make our opus sonorous, resonant. But even if that unimpeachable suggestion never comes, something proximate may be offered and that will prove immensely helpful, too.

One last thing I’ll say about this week, about what I think it’s about, is that it’s also a chance to model what this vocation looks like. To be clear: writing is a vocation; it chooses you, it compels you to do the work. We try to find jobs, if not careers, that allow us to pursue our vocation. If you’re not writing, then you’re thinking about how to write something, if not writing it in your head. And when you’re reading, you can’t help but scrutinize how somebody pulled something off instead of just enjoying yourself and moving on. The panels and the readings and workshops you’ll attend, and the conversations you’ll have, either informally or as part of your one-on-one meetings with staff, will impart to some degree how to think about your work and how to see yourself. I don’t mean in terms of oh, that’s what writers like to drink (usually that’s vodka), or that’s how writers dress (by the way, please don’t dress like me, if you can avoid it. My look? It’s a vestige of my days as a newspaperman, the People of the Rumpled Pants.) What I mean is how to see yourself as part of a larger, diverse, and vibrant group. We’re all in this thing together. Let us support each other, let us make a place at the table for those who are committed to the work. Let us help each other whenever and wherever we can. My hope is you will see many examples this week of what doing those things look like and how the role of writer—or even editor—extends beyond the act of wordsmithing.

You are all undoubtedly feeling spent, not only from the travel but from the excitement for what’s to come, so I won’t keep you any longer. I believe it’s a privilege to be here with each and every one of you. The world is still very much with us, even at this forested, vertiginous remove. Climate reckoning. Economic grotesqueries. The globe and our country teetering toward far-right authoritarianism. But here we are, together, to hone our craft so as to bring something of beauty, of humanity, of humor, of hope, out of all that chaos and anguish. Like I said, that trip here of many, many years ago let me know to whom I belonged, where I belonged. I belong here, and so do you. We’ll see you around. Good night.

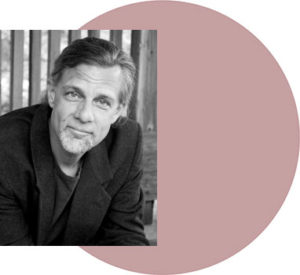

Oscar Villalon is the managing editor at ZYZZYVA, a recipient of the Whiting Literary Magazine Prize in 2022. His writing has been published in Stranger’s Guide, Freeman’s, The Believer, Literary Hub, and other publications. He lives with his family in San Francisco.

Oscar Villalon is the managing editor at ZYZZYVA, a recipient of the Whiting Literary Magazine Prize in 2022. His writing has been published in Stranger’s Guide, Freeman’s, The Believer, Literary Hub, and other publications. He lives with his family in San Francisco.

POETRY

Way Up Here, Where Sky Comes Close

A Golden Shovel for and after Al Young (1939 – 2021)

by Lisa Alvarez

Lisa Alvarez’s poetry and prose has been published in Air/Light, Anacapa Review, TAB Journal and others as well as anthologies including most recently Rumors, Secrets and Lies: Poems about Pregnancy, Abortion and Choice (Anhinga Press). She is the editor of three anthologies including Why to These Rocks: 50 Years of Poems from the Community of Writers (Heyday). Born in Los Angeles, she earned an MFA from UC Irvine and has taught for 30 years as a professor of English at Irvine Valley College. She co-directs the Writers Workshops, and serves as Assistant Program Director at the Community of Writers. Al Young was one of the first people she met at the Community of Writers when she first attended in the early 90s.

REMEMBRANCE

Remembering Al Young

by Barbara Tannenbaum

On the first Saturday of June, a far-flung community of artists, poets, and friends gathered at North Berkeley’s Hillside Club to pay tribute to Al Young and evoke his presence with loving memories. It was in keeping with Al’s disposition and poetic sense of timing that a bright sun broke through the miasma of gray clouds and rain that had been dogging the Bay Area for months. We walked up Cedar Street beneath the green canopy of Sycamore trees, taking comfort in the way their tall branches spread across the street. The crisp outlines of the leaves resembled giant hands stretching wide to clasp onto their counterparts.

On the first Saturday of June, a far-flung community of artists, poets, and friends gathered at North Berkeley’s Hillside Club to pay tribute to Al Young and evoke his presence with loving memories. It was in keeping with Al’s disposition and poetic sense of timing that a bright sun broke through the miasma of gray clouds and rain that had been dogging the Bay Area for months. We walked up Cedar Street beneath the green canopy of Sycamore trees, taking comfort in the way their tall branches spread across the street. The crisp outlines of the leaves resembled giant hands stretching wide to clasp onto their counterparts.

Al Young passed away from complications related to a stroke on April 17, 2021. That was during a still-acute period of the pandemic when health officials had just begun the fitful distribution of the very first round of Covid vaccines. It took another two years before event organizers, led by Al’s son Michael Young, poet and San Francisco State professor Persis Karim, and Joyce Jenkins of Poetry Flash, felt it was safe for the beloved community to gather in person. Since Al had lived down the block from the Hillside Club, the comfortable redwood-shingled social club built in 1898 in the Arts and Crafts style by Bernard Maybeck was the perfect venue.

At the corner near the club, someone had pinned Superman’s outfit to one of the Sycamore trees. Was it an official sign or did a child leave it by accident? No matter. By the time we approached the main room—really an auditorium with stained glass windows, a full stage, curtains, microphones, and seating for around 200 people—the music of jazz duo Tuck and Patti echoed to the street. It dawned on me that this memorial would be no somber event. We were in for a show.

At the corner near the club, someone had pinned Superman’s outfit to one of the Sycamore trees. Was it an official sign or did a child leave it by accident? No matter. By the time we approached the main room—really an auditorium with stained glass windows, a full stage, curtains, microphones, and seating for around 200 people—the music of jazz duo Tuck and Patti echoed to the street. It dawned on me that this memorial would be no somber event. We were in for a show.

We took our seats as Tuck Andress’s fingers moved in a blur across the guitar neck as he improvised a solo from a Wes Montgomery song — “Bumpin’ on Sunset.” Somewhere I heard that Al met Tuck and Patti on a jazz/spoken word tour they did sometime in the 1980s. In 2007, when Al was the Poet Laureate of California, the duo commissioned him to write the liner notes to their CD “I Remember You” featuring their take on jazz classics by Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, George Gershwin, and Nat King Cole. As several speakers reminded us, these musicians were among Al’s favorites. The music of Duke, Michael said, transported Al to a meditative calm even in his final days. Listening, he’d raise his good hand like a conductor to keep the beat.

“Remember this,” Al wrote on their CD: “In a world dismembered, violated, mutilated, ripped apart, the role of remembrance can’t be celebrated enough. Musicians are professional rememberers.” So, too, were the poets —Lee Herrick, Lisa Alvarez, Avotjca Jiltonilro, MK Chavez, Persis Karim, Mary Mackey, Kim McMillon, Marc Silber, Victor Hernandez Cruz, and Kim Shuck who evoked Al’s spirit, his love of the blues, and celebrated his insight that poetry was one of the original human languages.

“Remember this,” Al wrote on their CD: “In a world dismembered, violated, mutilated, ripped apart, the role of remembrance can’t be celebrated enough. Musicians are professional rememberers.” So, too, were the poets —Lee Herrick, Lisa Alvarez, Avotjca Jiltonilro, MK Chavez, Persis Karim, Mary Mackey, Kim McMillon, Marc Silber, Victor Hernandez Cruz, and Kim Shuck who evoked Al’s spirit, his love of the blues, and celebrated his insight that poetry was one of the original human languages.

We can always turn to Wikipedia for the majestic list of Al’s accomplishments, awards, and career highlights. We can even root around YouTube to hear again his deep, honeyed voice reading a poem or delivering a lecture. But of all the memories shared on stage, what stood out was the testimony by his friends, former students, and collaborators centering on Al’s rare gift of listening. The kind of serious, grounded, listening that elevated connection and conversation to something more like communion. Years, maybe decades have passed since those moments transpired. But each speaker’s eyes shone bright with the received gift of being heard, acknowledged on such a deep level.

My own connection with Al began as a student at the Community of Writers where he led one of our summer workshops. I can’t recall the piece of writing he was critiquing if that’s even the right word to describe what he did. Al said that hearing was the last of our senses to shut down when the body is dying. This was Al generously offering life wisdom to a bunch of kids who were barely into adulthood—myself included. What did I know of death? Well, it turned out that I was going to learn a helluva lot. It was the 1990s, an era marked by the decline and death of so many of friends who got sick during the AIDS crisis. And other crises, too. A car accident, cancer. I spent enough time in hospitals and ICUs to embrace Al Young’s offhand comment as a talisman. He guided me towards what I hope was my own loving and connected presence and conversation during those horrific years.

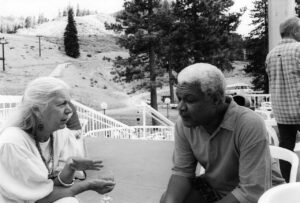

Remembering Al brought up other losses, too. I couldn’t help but think of his great friend, collaborator, and musical partner at the Community of Writer, Jim Houston. The generosity of these two men cannot be measured — the way they shared insights, made introductions for us, and had us believing we, too, could transport the complicated ephemeral world with all its beauty and emotional clarity onto the page. And so, seeing Jeanne Houston and her son in the audience and having a moment to chat was another grace note.

Perhaps a similar moment transpired when Ishmael Reed, who was tender and funny when speaking from the stage, posed for a photo with Kim McMillan and Carla Blank and his compadres from the Before Columbus Foundation, Victor Hernandez and Justin Desmangles. For a moment, no one had aged. There was not a gray hair to be seen — only Young Lions ready for another round of writin’ and fightin’.

It fell to the last speaker, San Francisco’s former poet laureate Kim Shuck to bring it all home. Quoting Al, Shuck closed with one final exhortation: “Remember to fly.”

It fell to the last speaker, San Francisco’s former poet laureate Kim Shuck to bring it all home. Quoting Al, Shuck closed with one final exhortation: “Remember to fly.”

Paying respects to a life well-lived — exceptionally lived — is a celebration. It expands one’s spirit. As we spilled out onto the sidewalk, I was again struck by the notion that the sense of hearing is the last one to shut down. If anyone could have heard every poem, every statement, every song uttered inside the Hillside Club that day, it would be Al. After all, he possessed an exquisite facility for listening.

A few days after the tribute, I felt compelled to return to Cedar Street and walk beneath the stately rows of Sycamore trees. There, I was surprised to Superman’s outfit missing from the tree. Had it been taken down? Not quite, I decided. I believe that it, too, remembered its purpose. It had taken off.

Barbara Tannenbaum lives in San Rafael, California. She is a former magazine editor and frequent contributor to museums including the California Academy of Sciences, Oakland Museum of California, and the Bundeskunsthalle Federal Art Hall in Bonn, Germany. As a freelance writer, she has had work appear in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and the Daily Beast. Her fiction has been published in the Chicago Quarterly Review and Catamaran Literary Reader. Her most recent essay, “James Dean in the Rear View Mirror” was published in issue #70 of Rosebud magazine.

Barbara Tannenbaum lives in San Rafael, California. She is a former magazine editor and frequent contributor to museums including the California Academy of Sciences, Oakland Museum of California, and the Bundeskunsthalle Federal Art Hall in Bonn, Germany. As a freelance writer, she has had work appear in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and the Daily Beast. Her fiction has been published in the Chicago Quarterly Review and Catamaran Literary Reader. Her most recent essay, “James Dean in the Rear View Mirror” was published in issue #70 of Rosebud magazine.

by Persis Karim

I first met Al Young when I was a student at UC Santa Cruz in the early 1980s. On the first day of my class in the Community Studies major, Al entered “Writing about Communities,” and greeted us warmly. I’ll never forget how his voice registered in the room, the way it connected us, the way he connected with his students. He asked us to help author an exquisite corpse poem about community, and what I remember is that he kind of sang it aloud after we were done in that beautiful bass voice of his. I had always wanted to be a poet, a writer, and it was in Al’s loving mentorship that that possibility opened for me. I was interested in writing about my family, about my immigrant parents, about the revolution that had just occurred in Iran and was scattering people around the globe. It was 1982, and Al did for me what he did for countless hundreds, if not thousands of students over the course of his life—he encouraged, cajoled, and supported me in my quest to be a writer. I would meet Al two years later after doing a six-month field study at the Black community newspaper, The California Voice, writing stories about the Bay Area Black community and learning so much about racism, and my own blindness. When I returned to write my thesis, Al was again my teacher and mentor, this time serving as my thesis advisor when one of the faculty members went on sabbatical. After several months of struggling to find the way to write about the experience, Al told me to abandon all the research on race and racism, to stop trying to write about a history of black exclusion and discrimination, but instead, to “write about what I saw, what I heard, who lives in that place. That’s what the world needs.” Al became my friend, was my poetry mentor, and was one of the first people to read the first anthology of Iranian-American writing I published. He wrote the introduction to the second book, Let Me Tell You Where I’ve Been: New Writing by Women of the Iranian Diaspora and I helped bring him to San Jose State when I was teaching there as one of the first Lurie Creative Writing Fellows. I know he had an impact on many students there as well.

I first met Al Young when I was a student at UC Santa Cruz in the early 1980s. On the first day of my class in the Community Studies major, Al entered “Writing about Communities,” and greeted us warmly. I’ll never forget how his voice registered in the room, the way it connected us, the way he connected with his students. He asked us to help author an exquisite corpse poem about community, and what I remember is that he kind of sang it aloud after we were done in that beautiful bass voice of his. I had always wanted to be a poet, a writer, and it was in Al’s loving mentorship that that possibility opened for me. I was interested in writing about my family, about my immigrant parents, about the revolution that had just occurred in Iran and was scattering people around the globe. It was 1982, and Al did for me what he did for countless hundreds, if not thousands of students over the course of his life—he encouraged, cajoled, and supported me in my quest to be a writer. I would meet Al two years later after doing a six-month field study at the Black community newspaper, The California Voice, writing stories about the Bay Area Black community and learning so much about racism, and my own blindness. When I returned to write my thesis, Al was again my teacher and mentor, this time serving as my thesis advisor when one of the faculty members went on sabbatical. After several months of struggling to find the way to write about the experience, Al told me to abandon all the research on race and racism, to stop trying to write about a history of black exclusion and discrimination, but instead, to “write about what I saw, what I heard, who lives in that place. That’s what the world needs.” Al became my friend, was my poetry mentor, and was one of the first people to read the first anthology of Iranian-American writing I published. He wrote the introduction to the second book, Let Me Tell You Where I’ve Been: New Writing by Women of the Iranian Diaspora and I helped bring him to San Jose State when I was teaching there as one of the first Lurie Creative Writing Fellows. I know he had an impact on many students there as well.

We stayed in close touch over four decades, going to lunch regularly after he moved to Berkeley to his favorite restaurants, Skates by the Bay, and Bacheeso’s, and we often went for walks at the Berkeley Marina. We talked about poetry, music, politics, our heartbreaks, and about writing. Even after he had served as Poet Laureate of California, I felt so few knew what a national treasure he was. I interviewed him and wrote a lengthy article, but it was rejected several times and after he passed away in 2021 the Los Angeles Review of Books published a much shorter version of that “recovered” interview. He deserved far more recognition and celebration; he was quite frankly brilliant beyond measure. I am glad that his papers will be housed at Harvard University, and I hope many future writers will bask in the pleasure of his poems, his prose, and his utterly original thinking about so much of life.

We stayed in close touch over four decades, going to lunch regularly after he moved to Berkeley to his favorite restaurants, Skates by the Bay, and Bacheeso’s, and we often went for walks at the Berkeley Marina. We talked about poetry, music, politics, our heartbreaks, and about writing. Even after he had served as Poet Laureate of California, I felt so few knew what a national treasure he was. I interviewed him and wrote a lengthy article, but it was rejected several times and after he passed away in 2021 the Los Angeles Review of Books published a much shorter version of that “recovered” interview. He deserved far more recognition and celebration; he was quite frankly brilliant beyond measure. I am glad that his papers will be housed at Harvard University, and I hope many future writers will bask in the pleasure of his poems, his prose, and his utterly original thinking about so much of life.

Al was a trusted friend, and someone on whom I had a lifelong crush. It was impossible not be charmed by him. He loved women, and especially loved smart women. I count myself lucky to have been one of those Al called a friend. He loved poets and writers and original thinkers. He loved people above all. And he inspired so many of us. I miss him so.

Song of You—

For Al Young

By Persis Karim

In the month of April, the month

Drenched in sunlight and poetry

You chose your exit. How fitting

That you slid out the back door

Like you were in the intermission

Waiting for the second set.

Your people, the poets and storytellers,

Know how much you loved this

Grand and epic life, the way

You showed up for it, that

Richness in your voice when you

Sang the tunes, no one’s voice

Could be this tender, this big,

This every kind of blue.

You gave us your music, your song,

Your lifelong love of being in it

All—blues, soul, jazz, and even

Folk—your instrument was full

Of pitch-perfect truth—

A golden truth we all needed.

You enveloped us in it with

That voice—velvet smooth,

Afternoon breeze, October pink—

I can still hear it all.

Persis Karim is a poet, essayist, and professor of Comparative and World Literature at San Francisco State University, where she also serves as the Neda Nobari Chair/Director of the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies. Her poetry has appeared in numerous publications including, Rowayat, Reed Magazine, Raven’s Perch, Callalloo, the New York Times, and others. She is the editor of three anthologies of Iranian diaspora literature. You can learn more at: persiskarim.com.

Persis Karim is a poet, essayist, and professor of Comparative and World Literature at San Francisco State University, where she also serves as the Neda Nobari Chair/Director of the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies. Her poetry has appeared in numerous publications including, Rowayat, Reed Magazine, Raven’s Perch, Callalloo, the New York Times, and others. She is the editor of three anthologies of Iranian diaspora literature. You can learn more at: persiskarim.com.Rain Drops & Dirty Sauce: 63-cent Impressions for My Son

by Hilary Zaid

This past fall, I picked up a genre of writing I haven’t practiced much since high school: handwritten letters. I have only one correspondent, my youngest son, and the ink only flows in one direction: from me to him. I don’t expect replies. They’re not the point. A letter is embodied, as in our lives together up until now we have been. Once, that was all we were, two bodies orbiting each other. Two bodies living together in the same space, sharing the same spicy chicken sandwich with dirty sauce and BBQ chips. I want to be with my son. So I tattoo little pieces of myself onto a page and send it to him.

Sending a paper letter to a 21st century teenager is not the obvious choice. Watching either one of my sons open an envelope is like watching a lion dismantle a small animal, only more violent. Before my older son left for college, I asked him to address a letter and realized, after a Cubist attempt, that he had no idea where to place a stamp. These aren’t stupid kids. They just didn’t grow up with paper letters. I did. I grew up getting birthday cards from my Aunt Selma stuffed with ten-dollar checks. I grew up penning passionate letters on rainbow paper and stuffing them through the slats of lockers. There’s a sense of presence you get with paper letters, a feeling of distance crossed.

So, when my youngest moved three time zones away, I started scooping 99-cent greeting cards off the rack at Trader Joe’s and dropping them in the mail. Trader Joe’s is the best greeting card bargain on the market, by the way, and the pictures and sayings aren’t bad. A dozen, colored lightning bugs blinking YOU SHINE BRIGHT! – I’m in. I want my son to know that I’m thinking of him even though he’s far away. But more than that, I need something to travel from my hands to his.

As a writer, my love of making things with words is a congenital condition, the craving for a deep-brain stimulation that comes from syllables and syntax and letters on a page. And it’s more than an abstraction. Most of the writers I know also love the physicality of writing, the haptics of it, the actual pen and ink and paper. Who among us doesn’t have a passionate thing for one special pen? Mine is the Pilot G-2 1.0, the boldest point I can find, and only in blue, black or the rare bright pink. The other inks don’t flow fast or dark enough. I’ve filled entire writing notebooks with sketches, characters and lines, only to mulch them in the backyard. I didn’t need what they said; the movement of ink across the page was enough.

Every week, give or take, I pick out a card, my Pilot G-2, and face the except-for-a-cute-or-witty- or-encouraging-pre-printed-quote blank page. Steve Almond once described the challenge of opening lines as driving up to your reader, flinging open the door, and convincing them to come along for a ride. I don’t think he imagined the reader might be one specific person willing to cut off a real, in-person conversation with a curt, “I’m done. This isn’t interesting.”

The results are messy. I’m not used to writing by hand at any length, and I’m often writing quickly, my hand cramping, trying to catch the mail carrier. I start on the pre-printed interior of the card, then run out of room, switch to the inside cover, run out of room again and then have to flip to the back, crazy little arrows pointing all over. Some of the cards are matte, and writing on the back is fine. But some of those back covers are glossy, and the ink smears if I don’t leave it out to dry, and then even if I do.

Mail service is highly variable in my neighborhood. Sometimes the carrier comes and sometimes they don’t, which means that sometimes my cards poke out of my box for days, waiting. One got blown away in a high wind before I found it days later in a bush. After it dried out, I drew an arrow on the back to the rippled skim of the raindrops and wrote: “This sat in a plant for two days in the rain!”

That’s the thing about letters that drew me to them in the first place. The physicality of them. Their life in the world. The way they have to travel through space and time, the way they perish, or endure.

Ten days before the end of the semester, I mailed my son the last letter of his first year. I wanted to make sure it didn’t miss him. Letters take time to get from here to there. That’s part of it, too. When he received it, he texted me, as he always does: “Got your card. Thanks.” He’s more polite now, my boy, since we’re no longer together. Thoughtful, even.

I don’t want to ask him what he’s been doing with these letters after he read them, though. Knowing him to be ruthlessly unsentimental, I guess that he’s thrown them away, or, at least, recycled them. But my son surprises me, revealing that he and I share a sensibility for written letters as things that not only connect us, but may survive us, and change as we, ourselves, are changing: “I’m saving your letters,” he tells me. “You never know. They might be interesting later.”

Hilary Zaid is a 2012 alum of The Community of Writers, where she was a James D. Houston fellow. Her forthcoming novel, Forget I Told You This (Zero Street Fiction, Sept. 1, 2023), is a queer, Jewish literary thriller about handwritten love letters and a plot against Big Data. Her youngest son designed the cover.

Hilary Zaid is a 2012 alum of The Community of Writers, where she was a James D. Houston fellow. Her forthcoming novel, Forget I Told You This (Zero Street Fiction, Sept. 1, 2023), is a queer, Jewish literary thriller about handwritten love letters and a plot against Big Data. Her youngest son designed the cover.

DISPATCH

Residuum

by Andrew Nicholls

For decades, if you were a television writer, it wasn’t hard to know when you were owed a residual payment. The rerun of your show was listed in the TV Guide. You saw: 7:30 p.m. LOVE BOAT. Gopher falls overboard (rerun), and you went out and put a down-payment on a car.

Writers’ unions tracked replays, collected mandated fees, and distributed them to their members. Residual amounts were negotiated by the Writers Guild of America during a 1960 strike as an integral part of initial compensation, as the word implies. Residuum = the remainder. Friends of mine vacationing in Bali once brought back an Indonesian newspaper listing my episodes, to help me keep a slippery international syndicator honest.

I first worked in network TV in 1981. That was under ACTRA, then the union for Canadian performers and writers. That year, I managed to get one sitcom script produced for national broadcast. Over twelve months, my writing partner and I each received C$818 in residuals, after C$1,500 in up-front pay.

There are currently over 1,000 episodes of TV in the worldwide syndication pool with my name on them, written for 42 different series. This total excludes several hundred episodes where I was the Creator or Executive Producer, rewriting others’ scripts, and short-order series which never syndicated. For those thousand episodes, many watchable for $1.99 on Disney, Apple +, Hulu, Netflix or the like, last year I received residuals from the WGA of $1,967. So, a little over double what I once got for a single episode.

Thanks to the WGA, I’ve had decent health care and a pension plan since 1984. But I no longer get meaningful residuals. With broadcast TV in a lengthening shadow cast by technological and ownership changes, there’s often no way for writers to know whether their shows are popular or are even playing in what the industry defines as the Market.

It’s also possible these days that people are essentially pirating them. One of my animated episodes, five years after its only season, had over two million views on YouTube. Who reaped the profits from those views, or from the ten YouTube channels that are playing that same episode today? In this case, YouTube’s owner Google, thus Alphabet, its executives and shareholders. As Scott Timberg wrote in his 2015 book Culture Crash: The Killing Of The Creative Class, much of YouTube is effectively a street sale of stolen goods, with Google selling maps to the looting.

But my episodes don’t need to be pirated by OklahomaCartoonFan to leak away into nothingness. In early 2023, I saw a bored child sitting near me with her iPad at a public event, watching something that I had written. Six years earlier, I’d pitched that half-hour, then wrote two outlines and three drafts, describing the guest characters, sets and props, writing the dialogue and orchestrating the chase sequences. It’ll run and be enjoyed presumably for as long as there are children wanting diversion. My pay in perpetuity for the episode was roughly the same as for that first half-hour I wrote forty-two years ago.

It’s a common reaction to writers’ strikes to say we shouldn’t complain: don’t we still make better money than a skilled auto mechanic? Aside from the obvious questions (shouldn’t we?), one might think of it this way: you’re an auto mechanic, but people only bring you one car every two months, and that’s in a good year. Then the owners showcase each car you’ve rebuilt and sell it for half a million bucks. And drag their feet paying you.

And after you turn forty, nobody brings you any cars at all.

The long-term profit of daytime animation is in the hundreds of thousands of dollars per episode. As half of a writing team on (for example) The Fairly OddParents, I received a one-time payment of $1,500 per script, minus an agent’s ten per cent. Nothing ever for my episodes that appeared on DVD, though the producers were contractually bound to track those. One Nickelodeon DVD of six Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius episodes was 50% my work. If they can slip out of admitting the sale of physical copies, how much easier is it to cry poor when shows are beamed directly into homes and devices?

Streaming has enriched every craftsperson it employs, but not proportional to their contributions. The goose is constantly being told her golden eggs are going out into a risky market with a lot of unknowns, and besides, the cost of collecting all that gold is high and rising.

We’ve been here before. After a 1973 strike, writers earned the right to receive extra payments when their TV or film work was repackaged onto home video. Videotape income for writers that year was zero. In 1973, I was in the Audio Visual Club at school – the tape was one-inch wide and had to be wound by hand around six capstans onto a sixty-pound machine with an exposed helical scan head that came up to speed with the sound of a vacuum cleaner sucking up porridge. In 1975, some friends and I rented Monty Python And The Holy Grail on videotape. It came on a reel the size of Elizabeth The First’s neck ruff. There was a $200 cash deposit for the machine and it took four of us half an hour to get it hooked up to the television.

By 1974, writers realized their first income from shows released on videotape: $15,029 in total.

By 1983, videotape revenue to writers was $4,408,510. That’s when the WGA noticed a little fast-shuffling had been going on. The 1973 contract with the producers had clearly and specifically stated the writers’ 1.2% would be based on “the worldwide total gross receipts derived by the distributor…” of the tapes. The producers had been paying us 1.2% of their gross, one-fifth of the correct amount.

The dispute went to court. It was a slam-dunk; all we had to do was wait for a judge who could read.

Then, in 1985, the writers’ Minimum Basic Agreement expired and the producers in essence said, “Look…we’ll bend on a lot of this stuff and dump an extra $1.25 million in your health fund, if you drop the lawsuit over videotapes.”

Like every proffer from the bosses, this was put to the membership for discussion and a vote. In heated meetings at the Hollywood Palladium, a right-wing faction within the Guild who called themselves the Union Blues militated to take the offer. The majority of the WGA’s writers, then as now, worked in TV, not in film. The Blues, whose twenty-one most prominent members were writer-producers earning a nice living that the strike had interrupted, loudly argued that television shows would never sell on VHS tapes or these “other as-yet-uninvented media.” People were never going to pay good money for copies of something they’d already seen for free on TV. Distributor’s gross, producer’s gross, it was moot: it wasn’t worth another week’s lost income to hold out for.

The Guild’s financial analysts and a handful of Board members and regular members on the Palladium floor pleaded for the membership’s forbearance – secondary-market distribution of TV programs was going to be big, and we had the AMPTP in a legal headlock. WGA President Ernest Lehman urged us to consider digital recording and cable delivery-on-demand. He spoke of the massive foreign market for American entertainment and the scary contractual generality of “other media.”

But the Blues continued to bully and yell and private-party their opinion. The producers’ offer was accepted by a 2,075-to-822 vote, and we lost videocassettes and, later, DVDs. Ten years down the road from that vote night, when you bought a copy of your favorite film, the writer of that film, who may have labored to get it made for five or ten years, who described every scene in his or her screenplay, plus wrote all the dialogue, got three and a half cents.

Ironically, when videotape was first introduced in the early 1970s, the Motion Picture Association of America had spent millions arguing to Congress that the availability of programs on portable, home-playable media would turn Hollywood into a ghost town. Instead, the technical revolution pumped billions into the industry and changed the way films and shows were sold and financed.

I have bad feet and an iffy back, but it looks as though I’ll be walking around tall buildings holding cardboard signs for a while, seeing if I can help shift some money away from the people whose keen professional insights told them no one would ever re-watch entertainment they’d already seen, and towards the next generation of people who actually create it. Honk if you see me.

Andrew Nicholls (participant, 2014) has written for television, stage and print. He’s the author

Andrew Nicholls (participant, 2014) has written for television, stage and print. He’s the author

of Comedy Writer (2020). He lives and pickets in Los Angeles.

I attended my first writing conference when I was in my 20s. It was a big milestone. Not only would I be in the workshop of an illustrious faculty member, I would be surrounded by students who were also on their way to bigger things. (Indeed, these other students went on to receive million-dollar deals, get long- and shortlisted for the Booker and the National Book Award, etc.) Everyone in my life was telling me the same thing: network your butt off at this conference because you never know when you might get to be in a room with some of these people again.

On the final or maybe penultimate day, my classmates decided to throw a party. It would be in the evening, after a full day of workshopping, panels, and individual meetings with faculty. By 4 p.m. I was already losing my shit. Every joint in my body hurt, the migraine storm front that had gathered on the first day had burst into multi-day torrential rain, and I no longer seemed able to form complete sentences. All I wanted to do was go home and lie down. But I didn’t want to admit to others that a week of being constantly surrounded by other people had worn me out, so I told everyone I couldn’t go to the party because I needed to go home and feed my cat—I would like to remind you that my brain had ceased to function by this point. One of my classmates patted me on the shoulder and said to me kindly, “Rita, that’s the worst excuse I’ve ever heard. Do you even have a cat?”

I did end up going to the party, but I don’t know how much networking I got done. Mostly I sat in a corner nursing my one drink because the only thing worse than being overstimulated was being overstimulated and ill. After the conference was over, I stayed in bed for days. That’s not hyperbole. I brought into my room a box of cereal and a jar of peanut butter and then subsisted off those things. My cat (yes, I do have one), elated by her sudden windfall, stayed on my lap almost the entire time and became very confused and infuriated when her unlimited access to Warm Sitting Place was eventually cut off.

And now, as I ramp up self-promotion for my debut novel, I can’t help but feel dread in addition to excitement about my book’s publication. And that really is a bummer because I should be celebrating this accomplishment.

I’m not the first to note the fundamental flaw to the premise that authors should self-promote. It takes a certain amount of introversion to tweak sentences in front of a computer for years at a time when somewhere there is a pickup game of basketball, a karaoke bar offering Happy Hour specials, a Stitch ‘n Bitch that’s really more about bitching than about stitching. Then the book comes out and we’re suddenly expected to know what to say and where to put our hands? At what point were we supposed to have acquired this knowledge?

If I don’t even know what to do with my hands, I can hardly be expected to self-promote. Here is a conversation I had with a friend recently while we were walking past a bookstore in her neighborhood:

Friend: Hey, you should go in and introduce yourself. Ask them to stock your book.

Me: No.

Friend: Come on, the more booksellers you convince to handsell your book, the better.

Me: NO.

Friend: Why not?

Me: Because I’ve never shopped at this bookstore before. They’ll judge me.

Friend: Fine, I’ll go in and tell them about your book. I’ve bought books there before.

Me: That’s worse! Then they’ll think that I’m too highfalutin to promote my own book!

I’ll spare you the rest of this conversation, but suffice to say the bookstore probably still

doesn’t know about my book.

Then there is social media. Being good at social media doesn’t necessarily mean you’re extraverted, though it does require you to be good at feigning extraversion. Depending on your platform/poison of choice, you must be skilled at making videos, writing pithy quips, or being hot. In the weeks leading up to publication, the pressure to vert extra-ly, to turn outward, intensifies. People are singing and dancing on TikTok and posting videos of themselves crying with their loved ones while unboxing their books. Meanwhile, I, a clumsy under-emoter with a limited vocal range, can only add exclamation marks to my social media posts in the hopes of coming across as peppy!! Let me be clear: I’m not judging these other authors. You gotta do what you gotta do to attract people’s attention in a society where the only sure way to get publicity is to be a celebrity with a sex tape.

It seems to me that authors are more and more graded not only on our work but also on our personality. Our likeability and relatability. People want to know our life stories (and whether those stories appear in our books). They want to know if they could see themselves as our friends. This is especially true in the case of women authors and authors of color. I Googled an author recently and the first suggested search under her name was ____ married? And here I thought the one thing uniting us as writers was that we were obsessive and generally difficult and therefore poor candidates for marriage.

But what are the options? Folks on Twitter might have read reporter Andrew Goudsward’s live Tweets last year about the Penguin Random House-Simon & Schuster merger trial, during which a publishing executive said outright that the Big 5 pay very little attention to the marketing and publicity of books they acquired for under $250K. How many authors can say they’ve had the good fortune of selling a book for more than $250K? Is it any wonder, then, that people feel pressured to do literal song-and-dance numbers, to RSVP to every invite? So, until the system changes, don’t hate on authors for being loud about their books. Chances are, most of us don’t want to be doing this in the first place.

Rita Chang-Eppig’s novel about an infamous Chinese pirate queen, Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, is an Indie Next pick for June 2023 and an Indies Introduce pick for Summer/Fall 2023. Her stories have appeared in The Best American Short Stories 2021, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Conjunctions, Clarkesworld, Virginia Quarterly Review, One Story, and elsewhere. She has received fellowships from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, the Vermont Studio Center, the Writers Grotto, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University.

RECIPE

Chocolate Cream Caramels

by Natasha Saje

Like many things I make, this batch of candy resulted from my own craving. Why buy caramels if they are likely to be too sweet, stale, expensive, or all three? These scratched the itch and were easy, even without a candy thermometer.

1 pint heavy cream

2 1/2 cups sugar

1 cup corn syrup

1/2 tsp salt

10 ounces bittersweet chocolate (I used 75%, you could make them more bitter by using a higher cocoa percentage.)

I stick unsalted butter

1 tsp. vanilla extract

flaky sea salt for garnish

Line an 8×13 (or so) pan with parchment paper. (The smaller the pan, the higher the caramels.) Spray the parchment with cooking spray.

Whisking constantly, simmer the cream, sugar, corn syrup and salt until it thickens slightly and reaches 220 degrees, 10-15 minutes. Off the heat, whisk in the butter and chocolate. Cook (and whisk) until it reaches “firm ball” stage (240 degrees)–this may take 20 more minutes. Be patient. You’ll see the mixture thicken yet again; the simmering bubbles will be large. To test, put a bit on a cold plate and see if it holds its shape. Stir in the vanilla and take off the heat.

Pour into the prepared pan and sprinkle the top with Maldon or other flaky salt, as desired. Allow to sit 8-12 hours in a cool place. Unmold onto cutting board and cut into squares or rectangles, then wrap each piece in parchment or wax paper.

Natasha Sajé’s books include The Future Will Call You Something Else (Tupelo, 2023); a postmodern poetry handbook, Windows and Doors: A Poet Reads Literary Theory; and a memoir-in-essays, Terroir: Love, Out of Place (Trinity UP, 2020). She teaches in the Vermont College of Fine Arts M.F.A. in Writing Program and lives in Washington, DC.

ESSAY

I Am the One Who Wrote It

by Jasmin Hakes

I spent ten years trying to write a book that refused to work. I was single mother of two struggling to make ends meet. For that decade of my children’s lives I carried index cards around in my purse at all times, stealing minutes in movie theatres and soccer games to hastily jot down sentences and thoughts I wrote down not because I thought I’d actually have time or ability to turn them into a book one day but out of an attempt to stay sane. They were haunting me, these thoughts, and writing them down was the only way to get them out of my head. I couldn’t explain to my kids why my attention was always only half in the room; I could barely understand or explain what was happening to me. And to then turn them into a book felt like the natural next step to finally being “free” of this haunting.

After a decade, though, I had had enough. I couldn’t justify it anymore. So, after countless “loved it, but” from agents, I shelved it, swearing I would never write again.

Two weeks later, I wrote Hula.

I had been awarded a prestigious literary fellowship that gave me three full weeks in a cabin alone. No cell service, no internet. Which might sound more like a punishment for some, but writers (and single parents) would understand all that solitude implied.

I was mentally exhausted. I didn’t have an MFA, so I’d been trying to learn how to write any way I could and had reached a wall. No matter how hard I studied books on craft or my own cobbled-together literary canon (a term that, admittedly, I had to look up after nodding cluelessly through a dinner surrounded by accomplished, educated writers from elite MFA programs), my writing went from stilted to stuck. So when I accepted the aforementioned fellowship, I accepted with the assumption I would be staring blankly out a window for three weeks. I had no intention to write. But it took a plane, a bus, a ferry, and a van to get me there, and somewhere in there a sentence popped into my head. It was entirely new. The thought of embarking on an entirely new project made me want to cry, so I wrote it down while reassuring myself that this meant nothing, that I merely wanted to see what those words in my head looked like on paper. As soon as that one was out another arrived in its place, so I wrote that one down too.

Three full and exhausting weeks later, I had a very messy but nearly complete manuscript. I knew instantly that there was something different about it. Whenever I read a few pages out loud, my hands shook. My voice cracked. There was an energy in whatever this thing that had poured out of me was that I had not experienced before. But instead of being excited, I was terrified.

Like many novels, the story germinated from my life. I grew up in Hawaiʻi and am from a local family proud of its Hawaiʻi roots, but I looked more like a tourist. The story grew on its own from there. It explores all the historical reasons why being from Hawaiʻi is not the same thing as being Hawaiian. It questions the definition of belonging, of who belongs and who gets to say. It traces the ripple impact colonization continues to have on Hawaiʻi, as well as the scars left from the theft of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Basically, it asks all the questions I had had all my life but had been too scared to voice because I was scared of what the answers might be.

I know not everyone will be happy I wrote it. It was a story written to start a conversation, but I know there’s a chance that the fact of me writing will be what sparks debate or controversy because we are still operating in a world where we’re all trying to figure out who gets to tell what stories and who those stories should or should not include.

The parallels of that are not lost on me.

Jasmin Iolani Hakes was born and raised in Hilo, Hawaii. Her essays have appeared in the Los Angeles

Jasmin Iolani Hakes was born and raised in Hilo, Hawaii. Her essays have appeared in the Los Angeles

Times and the Sacramento Bee. She is the recipient of a 2018 Hedgebrook residency. Hula, out now

with HarperVia, is her debut novel. She lives in California.

ESSAY AND EXCERPT

Yes, I Said, Of Course

by Stephanie Austin

My relationship with my publisher, WTAW, was a funny mutual finding. My friend Sara Lippmann sent out a blast saying the press was opening their reading period, so I submitted my novel, which they rejected, but inside the rejection, the publisher said she’d seen my essay in The Sun and by the way, they were launching a chapbook series called Alcove Chapbooks Series and I should consider submitting CNF/memoir for their upcoming launch/contest. Yes, I said, of course.

That Sun essay itself, about my father’s death and my relationship with him, also started a little happenstance. I never sat down to write an essay. I sat down to write down the stories I tell myself and others about my father. My father was a high-functioning alcoholic. I wanted to see what else was there. Was I wrong? Was he better than I remembered? In his later years, when

his health was failing, the two of us got along fine. He needed me. When he was dying, I realized, maybe, and this was hard to admit after years of disconnecting, that I needed him.

Since 2017, I’ve suffered a constant barrage of loss. It seems I’m focused on the death day or the immediate aftermath. The plane ride home from my cousin’s funeral. Picking up dog toys from around the house. Standing on the sidewalk watching them take my grandma out of her nursing home. Even without the pandemic, the weight of grief I’ve walked with over the past few years has felt unbearable. Confronting death on so many levels felt unbearable. The act of writing is an act of hope. We all hear that. The act of writing is also an act of self-preservation.

Excerpt:

Summer break from college, 1998. I was at my dad’s house waiting for my boyfriend to call. I took the cordless phone off the cradle and made sure it worked. I moved the phone from the countertop to the kitchen table as though that might make it ring. My boyfriend knew I was back in town and still he had not called nor returned any of my phone calls.

“What are you doing?” my dad asked.

I was being desperate and sad, but I could not let my dad know this. Maybe this weekend my boyfriend and I would go out to dinner, hold hands in public. Maybe this weekend he might acknowledge me as his girlfriend.

My father was waiting for an answer. “My boyfriend—” I began.

“Boyfriend?” he said. “Who is he?”

I told him the boy’s name and a little about our relationship.

“He’s your boyfriend?” my dad asked again.

Did I need to spray-paint it on the wall? Boyfriend. Boy. Friend.

“He doesn’t sound like a boyfriend, if he only calls once a month.”

“You do not get to tell me who is or isn’t my boyfriend, Dad. I know.”

My mother and I had already discussed this. She’d said my dad had been the same way when they were dating. Distant. Calling only when he felt like it, or when he wanted something. Partying. Going out with other women. She said this had continued into their marriage.

But they had gotten married, I pointed out to her. So, there was hope.

She reminded me that her marriage to my father had imploded. They’d been divorced longer than they’d been married.

My dad repeated, “I do not think he is your boyfriend if he doesn’t call.” In his way, he was telling me to expect better for myself. This guy was not treating me well. My father’s own actions showed me otherwise, and I could not reconcile the two.

from Something I Might Say – WTAW Press

Stephanie Austin has published more than 25 short stories and essays in numerous literary journals. Her chapbook, Something I Might Say, was published on July 18 from WTAW Press. You can read more at stephanieaustin.net. She runs Mugshot Writers on Instagram @mugshot_writers2. Follow her on social media on Twitter: @lucysky and IG: @stephanie.d.austin

Stephanie Austin has published more than 25 short stories and essays in numerous literary journals. Her chapbook, Something I Might Say, was published on July 18 from WTAW Press. You can read more at stephanieaustin.net. She runs Mugshot Writers on Instagram @mugshot_writers2. Follow her on social media on Twitter: @lucysky and IG: @stephanie.d.austin

COMMUNITY (RENGA)

In the Long Shadows of the Pines

by Frank Karioris & the CoW Poetry Workshop

Preamble

As Galway Kinnell famously said, “when poets gather in a community to write new poems, each poet may well break through old habits and write something stronger and truer than before.” At this year’s Community of Writers Poetry Program, we worked to live this ethos out by participating in a remarkable, collaborative, poetic practice: writing a renga.

A brief, non-expert, background on the form and practice might be helpful. A renga is a form of Japanese poetry whose practice dates back to at least the 8th century. Written collaboratively, each poet takes turns writing a verse. The verses alternate between a stanza of three lines, with 5-7-5 syllables; and a two-line verse of 7-7 syllables. (In Japanese, these units are measured in mōra or haku – sound or phonetic unit – rather than syllables.)

A brief, non-expert, background on the form and practice might be helpful. A renga is a form of Japanese poetry whose practice dates back to at least the 8th century. Written collaboratively, each poet takes turns writing a verse. The verses alternate between a stanza of three lines, with 5-7-5 syllables; and a two-line verse of 7-7 syllables. (In Japanese, these units are measured in mōra or haku – sound or phonetic unit – rather than syllables.)

Structurally, the renga begins with a hokku (発句), composed by the ‘host’ or a senior poet, which can stand independently as a poem unto itself, and which sets the tone and trajectory of the poem. Once the poem and participants are ready, the renga then ends with the ageku (挙句), which wraps together and concludes the piece thematically. (The hokku and the 5-7-5 verse form later developed into a distinct form of its own, the haiku.)

During a renga session, there are three categories of writers: the renju (連衆) or participants; the sōshō (宗匠) or master, who is in charge of the opening hokku and sets the tone for the poem; and, finally, the shuhitsu (執筆) or scribe, who acts as the organizer of the session, was in charge of the documentation & transcription of the poem, and who acted as a sort of moderator, ensuring the renju knew the practical rules or guidelines to follow.

For our renga, as scribe, I put forward a set of guidelines that sought to stay rooted in the driving ethos of community. Each poet was given four minutes to write their verse – encouraging poets to live in imperfection and temporality. The fushimono (賦物) or ‘prompt’ of our renga was broadly to take inspiration from our time together as community as well as the verse immediately preceding – whether a word, tone, image, emotion, or otherwise – and incorporate this inspiration into the next verse.

For our renga, as scribe, I put forward a set of guidelines that sought to stay rooted in the driving ethos of community. Each poet was given four minutes to write their verse – encouraging poets to live in imperfection and temporality. The fushimono (賦物) or ‘prompt’ of our renga was broadly to take inspiration from our time together as community as well as the verse immediately preceding – whether a word, tone, image, emotion, or otherwise – and incorporate this inspiration into the next verse.

Over the course of the second half of the week, seventy-one community members – including participants, staff, staff poets, and directors – offered a verse to the renga. The poets not only gathered in community, but came together as community to accomplish a task bigger than themselves and their individual poems. In coming together to write this poem, the ethos that Kinnell laid out is given wonderful, new illustration.

Throughout the week, the gathering of this poem became a large part of my poetic work. As such, and with great joy and humility, I am extremely honored to have played a part in bringing these accomplished poets together and to share the spirit of community that was created in the valley.

In the long shadows of the pines

Community Renga (June 2023)

June, late afternoon

long shadows of the pines

on the right field grass.

A softball soars to the east –

A blackbird glides to the west

Hidden redwing tips

secret gift pushes on through

Dark powers keep beating.

The horizon disappears

& then the people emerge

like ghosts, they breathe blue

suns over the horizon –

every ray a wing

Sweet pea where it shouldn’t be

purple in the wrong places

Let go. Let go – hold

onto the crescendo let

purple rain ring loud.

loud like pepperoncinis

spicy like the forest air.

and when up this high

the breath thins but tenderness

abounds between lines.

gratitude gratitude

feel my gratitude flowww

I’m soft, delicate

flamboyant, extra some say

I’m fabulous. Slay.

Fabulous fabulous pines

reach for ocean spray and waves.

The water cleanses,

our spirits are happiest

here at Lake Tahoe

turning water into wine

the body now haunted.

Wish for warm water

sand that holds my history

even among new friends.

Lake water whispers, whistles

into an errant pine cone.

The snow melt beckons

offers reverie and shock

star shape flouting back.

horizon answers water

water answers sky and rock

the telephone rings

sky is on the other end

water, we have to talk.

moon moon moon moon moon moon moon

sea sea sea sea sea sea sea

A lake like a sea,

fighter jets fly overhead –

awash in their sound.

Grandmother Water! You’ve been

Washing your stone child how long!?

because we couldn’t

count on these torrents of rain

to keep ourselves young.

I am a desert of love

wet me with your fresh vigor.

Deserted again –

what good would vigor do me?

Why not a rebirth?

Time to reacquaint myself

with water like marula trees.

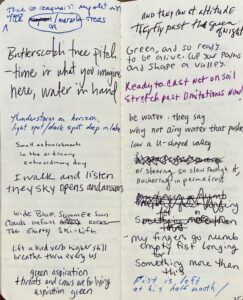

Butterscotch tree pitch

– time is what you imagine

here, water in hand.

Thunderstorm on horizon,

light spot/dark spot deep in lake.

Small astonishments

in the ordinary

extraordinary day.

I walk and listen to all

they, sky, opens and answers.

Wide Blue. Summer Sun

Clouds unfurl along rocks –

The empty ski-lift.

Lift a bird verb higher still

breathe thru every us.

green aspiration

throats and crows are for lying

aspiration green

and they can at altitude

they fly past the green of night.

Green, and so ready

to be alive. Cup your palms

and shape a valley.

Ready to cast net on soil

stretch past limitations now!

be water, they say

why not airy water that pushes

low a u-shaped valley.

or steering so slow through it,

anchoring in permafrost.

– my fingers go numb

empty fist longing for

something more than this.

Fist is left at his half mouth

fingers determined false anger.

Egg sandwich chomped

the day is less than it is,

empty five fingers.

Five nights of silence or sound –

which would you, dangereuse, choose?

Fear within and fear

without daring will matter

among the snow melt.

Four fingers within ghost

wonderlesslist white memoir.

Four orange columbine

flowers, finger wet wind sound

like thunder’s bare breath.

Lightning cracks, breaks a ribcage

of light sparking a fire, burning.

Cracking our lives back

we go on & on burning

so bright bold fires sing.

Where open husks of aspen

seeds rain, and cowbird song rains.

Husks reopen faithful

to nothingness aplenty,

for now forever.

Seeds falling out of silence

Silence growing here like phlox.

Skeletal branches

beckon me forward like mo-

-ther reaching to child.

greenmother I know is god,

god being me in the sky.

So irreverent

All the little dots be-low

I pet my dogma.

Spots appear in my vision

I watch the sun too closely.

Sun says, go to sleep

it’s the edge of Friday’s end

soon your head will loll.

Son says sun says not yet I

see his eyes and mine old reds.

The moon speaks too, she

tired from constant wakings

finds patience, kindness.

Instantiated sky pose

stars muster a fickle burn.

Fickleness! didn’t

Juliet say, “swear not by

the inconstant moon”?

Moon: who would dare to swear me

Spiders spin my sticky hour.

Sleep-webs in the morning

see complicated aspens

it’s a bad hair day.

It’s a good air day. Pines breathe.

In the valley, they’re leaving.

Flashing their underbellies

Aspen leaves quiver in sun.

All my loves have died.

All my loves shouldn’t have died

It’s always the loves that leave.

Leaves leave every day

Day to day Toad Day, Damn.

It’s cold still today.

Gucci Mane said brrr cold fur –

ice stopped me on the way, fuck.

Lamp post shock reveal

poster pealing degrade

reveals through torn dark window.

messages lost are endless

their human-made tape lingers.

i hold the button,

erase the digital trace

of loss. losing loss.

Finding freedom in the form

of time-does-not-exist, friend.

A community

held by summer pines. Friends, now

become creek bed rain.

Frank G. Karioris (he/they/him/them) is a writer and educator based in San Francisco whose writing addresses issues of friendship, gender, and class. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in Pittsburgh Poetry Journal, Collective Unrest, Riverstone, Berlin Review of Books, and in the collection Eco-Justice For All, amongst others. They were a W.S. Merwin Fellow at the 2023 Community of Writers Poetry Program.

Frank G. Karioris (he/they/him/them) is a writer and educator based in San Francisco whose writing addresses issues of friendship, gender, and class. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in Pittsburgh Poetry Journal, Collective Unrest, Riverstone, Berlin Review of Books, and in the collection Eco-Justice For All, amongst others. They were a W.S. Merwin Fellow at the 2023 Community of Writers Poetry Program.

ABOUT THE OGQ

Omnium Gatherum Quarterly (OGQ) is an invitational online quarterly magazine of prose and poetry, founded in 2019 as part of the 50th Anniversary of the Community of Writers. OGQ seeks to feature works first written in, found during, or inspired by the week in the valley. Only work selected from our alums and teaching staff will appear here. Conceived and edited by Andrew Tonkovich. Submissions will not be considered.