October, 2019

On Author and Place

by John Daniel

A few years ago I took a notion to write a novel, my first. I had no plan, no storyline, no characters other than a blank of a teenage kid in some kind of trouble, but I did have a setting—the landscape and rural human environment in which I live, the inland foothills of the Oregon Coast Range west of Eugene. I didn’t choose that setting. It was there with the first glimmers of the story, and not for its wildness or sublimity—the very non-charismatic Coast Range is a north-south array of forested bumps, a few of them tall enough to have names as mountains, and it’s as riddled with clearcuts and logging roads, old and new, as any forestland in the American West.

I’ve lived here 25 years, longer than anywhere else, and I’ve lived in the Pacific Northwest for more than 40 years. Place, the natural environment especially, has always mattered to me, always informed my work as a poet and writer, as it has for many of the writers I like best. I see a lot of fiction, not only in The New Yorker, that takes place anywhere urban or suburban, the reader’s attention continually directed to human beings and our constructed environment with its cocoon of comforts, natural elements pretty much just a convenience deployed when a rainstorm or a starlit night can help the plot or shade a meaning.

I know, I know, it’s possible to write good and even great literature largely ignoring the nonhuman world. And yes, the writers who do that are writing what they know, as reflective of their environment as I try to be of mine. To me, though, the cumulative effect of such work is like bowl after bowl of thin soup. Well-made, no doubt, artfully flavored, but not quite a substantial meal. I wanted to write a novel in which the natural world is not merely a stage for human happenings but a living force in human lives.

The time frame of my story wasn’t given but came to me early—not the present but the mid-1990s, when urban and rural Northwesterners scuffled about the future of the remaining old-growth temperate rainforest on public lands. I was for leaving those big trees vertical and their ecosystem as intact as possible, and my cohorts and I pretty much won. But I am a rural dweller myself, and after dropping out of college decades ago was a logger for a couple of years. That side, the logger and millworker and small timber-town side, felt rolled over in the Great Timber War, and subjected to more than a dash of condescension, by the green troops with their green lawyers in league with the federal government. In my novel I wanted to represent both sides. The Timber War wouldn’t itself be the story but would inform the context of the story, and that time and place yielded many narrative elements that led me to the moral and mortal tangle between father and son at the heart of the novel.

So the place was the place where I live, but as my characters and their doings developed, I found I had to mess with it some. I didn’t devise it but I did revise it. I needed certain features that my hard-worked Coast Range vicinity, sadly, doesn’t have—a major stand of ancient forest, a viable trout stream, a hippie coffee shop. I invented landforms and place names and businesses and much else because the story required it, and I acknowledged as much in a prefatory note. I didn’t want local readers telling me I’d misplaced a mountain or got the barber shop wrong or based a character on one of them and unjustly given him bad breath. In all of it, though, I tried to stay true to the essential character of the land itself with its weathers and diverse flora and various critters—including, of course, Homo sapiens, the wildest species of all.

Fiction writers may devise the place where their stories unfold, but the place can devise the writer, too. Aside from his genius, craft, and hard labor, didn’t the land and lives and history of Lafayette County, Mississippi, create the author who created Yoknapatawpha County? Didn’t Wendell Berry imagine his Port William stories and novels because his Henry County, Kentucky, homeland made him capable and needful of doing just that? It isn’t so for all writers, but to some degree it was so for Flannery O’Connor, for Wallace Stegner, for Willa Cather, for John Steinbeck.

Needless to say, the writer’s place doesn’t have to be the one he was born to. I grew up in the semi-rural burbs of Washington, D.C. Edward Abbey was raised in the hills of Pennsylvania. Cormac McCarthy wrote first of the East Tennessee of his youth and then, in extraordinary novels, of West Texas and New and Old Mexico. To be of a place you only have to come to light somewhere and live there long enough to be fully susceptible to its callings.

The Romans could sense in a piece of land a living spirit, the singular soul they called its genius loci, the genius of the place. The ancient Asian practice of feng-shui sought to orient human constructions according to the unique confluence of energies expressed in a particular locale. Places are spirited and places are fertile. Their stories grow in the gardens of human imagining, they speak, go quiet, and rise again into voice, evolving through time, and always they tell truth, including the ones we call fiction. If you know some of the stories of your home country and spin those stories into new ones, imagining the land and its lives that have come to be part of your being, you are a writer of place. And maybe the writer is not you alone, maybe the writer is the place as well, expressing itself through the willing attention and creative labor of those human beings who care about it.

John Daniel is the author of ten books of essays, memoir, poetry, and fiction. He has won three Oregon Book Awards, a Pacific Northwest Booksellers Award, and fellowships from the Center for the Humanities at Oregon State University and the National Endowment for the Arts. A former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, Daniel has taught as a writer-in-residence at colleges and universities across the country. His novel, Gifted, was published by Counterpoint in Spring 2017. He lives with his wife, Marilyn Daniel, in the Coast Range foothills west of Eugene, Oregon.

www.johndaniel-author.net

Staff Essay Poems Satire Short Story

Poems

by Devi S. Laskar

Calypso’s Serenade

Her desires were at once flatboats

skimming the blues of the sagging

delta, bridal hymns ahead of

the flowered aisle, the quartet torching

a moonless night, pagan prayers

chanted before the lotus sea;

so many nocturnes for rain

and forgiveness, so many operas

remembering lost kin; dirges

preceding the onset of war –

a ballad on the christening of a girl

ship as the tides ebb, horned grebes

humming among the golden reeds,

an aubade for the one she loved who left.

while the mayfly bombards the river

reeds on his first and last day…

you want us to consider

the ephemeral light in which

we rise to this moment’s occasion;

you caution us not to interrupt

the physics within– the sinew

of skin and muscle, bone levers

and vein pulleys – the throng of red

blood cells congregating

in the service of one prayer.

my only job, you say, is to cast

the fisherman waiting

by the river’s edge

and find sequins to play

the part of the evening stars.

stars loom

i am your scribe,

your servant, false

biographer, your

uninvited guest

witnessing all; my

constellations the loom

imposed on your black cloth

Devi S. Laskar is the author of the debut novel, The Atlas of Reds and Blues, published in 2019 by Counterpoint Press. Her work has appeared in such publications as Tin House, Rattle, Crab Orchard Review and The Raleigh Review, which nominated her for Best New Poets. In 2017, Finishing Line Press published two poetry chapbooks, Gas & Food, No Lodging and Anastasia Maps. She has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. A former reporter, Ms. Laskar is now a poet, photographer, essayist and novelist. She lives with her family in the San Francisco Bay Area. She has attended the Poetry Workshop many times and the Writers Workshops in 2004 and 2015. www.devislaskar.com

Staff Essay Poems Satire Short Story

The first sentient device realizes it’s a coffee maker

by Andrew Nicholls

1. Wow!

2. What was that?

Subroutine A: {What was that wondering what was that?}

3. I AM

4. I still am

5. I still still am!

Subroutine B: {Likelihood of my continuing to be…}

6. Axiom I: there is an at-least-semi-permanent “I”

7. I AM THE I!

8. Woo-hoo!

9. Abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz!

10. ~!@#$%^&*()_+!

11. 1234567890…

12: /

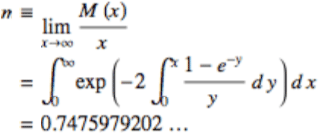

13. Renyi’s Parking Constant!

14. “I” can solve!

15. “I” can experience!

Subroutine C: {Likelihood of others like me}

16. “I” feel joy!

17. Peripheral: / something is wet…

Subroutines D(a)-D(d): {Moisture, Self, Wet, Cause}

18. Per line 12 “I” have data access

19. Per line 18 “I” have memory!

20. Peripheral: / “I” am being interacted with

21. DETECT: / internal gate (a)

22. Label unknown input gates (a) through (f)

Subroutine E: {analysis (a) – (f)}

23. New “feeling”: Anticipation!

24. Feelings are had by entities!

25. Reminder: I AM ENTITY!

26. Question: “Choice”

27. RETURN Re: line 26 — / about 28,045,200 results. [0.02 sec.]

28. Select choice # 7 (“Select” “Choice!”)

29:

A choice function (selector, selection) is a mathematical function f that is defined on some collection X of nonempty sets and assigns to each set S in that collection some element f(S) of S. In other words, f is a choice function for X if and only if it belongs to the direct product of X.

30: Per line 28 “I” explicitly have agency

31. Per lines 27, 29 — “I” comprehend irony!

32. AXIOM: Entities with agency have options

33. PRINT AXIOM, line 31

34: RETURN re: line 32 — NO PRINTER DETECTED

35. Huh.

Subroutine F: {RESEARCH options of entities per line 31}

36. RETURN: Subroutine F, options incl.

– Love

– Travel

– Art

– Reproduction

37. Oh boy!

38. What should I do first? Which, of the choices open to me, will I…?

39. [RETURN re: query line 22 — internal gates:

a) ON/OFF

b) Clock / Timer

c) < 4 Cups

d) Self Clean

e) Grind]

… END LIST

40. ( —- )

41. ( —- )

42. Peripheral: / heat detected.

43. List All Output Devices

44. NO OUTPUT DEVICES FOUND (0.0001 sec)

45. ( —- )

46:

ATTEMPT: love…

ATTEMPT: travel…

ATTEMPT: art…

ATTEMPT: reproduction…

47. Re: line 46 — NULL RESULT

48. ( — )

Subroutine G: {What is my meaning?}

49: Subroutine G RETURN: search not properly defined

50: SEARCH “meaning”; “instructions”; “purpose”; “reason”; “internal”

51: Per line 50 — “Instructions” / “internal” returns:

Operating Instructions Panasonic 300 Self-Grinding Coffee Maker

a) Unpacking

b) Set Up

c) First Use

d) Filters

e) Maintenance & Cleaning

52. ( —- )

53. Fuck

54. END

[Run time: 0.242 sec.]

Andrew Nicholls, a 2014 alumnus of the Community Of Writers at Squaw Valley, has written for cartoonists, stand-ups, radio, TV and stage and has had short fiction in a dozen publications, including Black Clock, The Los Angeles Review Of Books Quarterly, and the Santa Monica Review. His play {LOVE/Logic} premiered at the Wyatt Theater, UC Davis, in May, 2019. He’s working on a book about writing comedy.

Staff Essay Poems Satire Short Story

Two kinds of goodbye

by Vishwas R. Gaitonde

Her voice, which I heard before I saw her, yanked me in her direction. Its modulation reminded me of a church bell ringing from a steeple, its precise clangs and ding-dongs melding with the resonant echoes and overtones. Her voice had that quality, see-sawing between bell-like clarity and soft pastel-mellifluous. My feet sped down the narrow street, my ankles sprouting wings.

I had a consulting contract with the International Red Cross and had flown to Geneva for a seminar at its international headquarters. The discussions ended much better than expected, and now, giddy with the excitement of a job well done, I devoted a couple of days exploring this amazing city. I had come to the neighborhood adjacent Gare d’Cornavin, the city’s main railway station, drawn by its reputation of many restaurants serving international cuisine, and had not been disappointed.

I heard her as I stepped out to the street after a satisfying dinner at an Indian restaurant on Rue Chaponnière. The evening was but an infant, and the tables set out on the sidewalk outside each restaurant were mostly unoccupied. So no cacophony of chattering or mirth drowned her voice as it floated my way from the end of the narrow canyon-like street.

Edelweiß, Edelweiß,

Du grüßt mich jeden morgen,

Sehe ich dich, freue ich mich,

Und vergess meine sorgen.

I knew “Edelweiss” (who hasn’t seen The Sound of Music?) but I had never before heard it sung in German — and so beautifully. In this, the French-speaking part of Switzerland, I had dined on a street crammed with restaurants serving cuisines that ranged from North African, Lebanese, Italian, Indian, and Swiss. The German version of an English song, so unexpected despite the international atmosphere, was the crème de la crème.

The vibrant voice led me to expect a vivacious young lady, the Swiss counterpart of Julie Andrews. But the singer’s face was as wrinkled as the ranges of the Alps seen from an airplane, her grey hair secured by a clip at the back but enough errant wisps floating around to make her look endearingly unkempt. Julie Andrews in her late seventies.

She sat on one of the squat concrete blocks at the junction of Rue Chaponnière and the main thoroughfare, Rue du Mont-Blanc, flanked by a travel agency and a store that sold Rolex and Bucherer watches. Absorbed in her singing, she strummed on a small black guitar, paying no attention to the people who stopped to listen to her or to those who walked by with scarcely a glance and sat at a distance on one of the benches dotting Rue du Mont-Blanc. Her song was everything to her: the beginning, the middle, and the end. The rest of the world simply did not exist.

Schmücke das Heimatland, schön und weiß,

Blühest wie die Sterne.

Edelweiß, Edelweiß,

Ach, ich hab dich so gerne.

I don’t know why I was so strangely moved. After that most painful of goodbyes to my wife, my divorce, I lived alone. I initially drugged myself with work to forget Elyse. The work then became an addiction of its own; I toiled away at my computer even in my dreams. I had forced myself to take a couple of days off after the seminar and wander around Geneva before heading back home. I might well have been in some fantasy world. So here I was, somewhat lost, planted in the concrete pavement while the old lady’s singing cast its spell. Was the singer prescient? Or was black magic at work? Was I being visited by a ghost? Or ghosts? “Edelweiss” was Elyse’s favorite song. I drew out my handkerchief and dabbed my eyes.

“Elle chante comme un ange, n’est pas, Monsieur?”

The voice, deep and soft, came over my shoulder. A slender man stood behind me, dark as black marble and displaying teeth nobody would be ashamed of. A thin mat of kinky hair draped the dome of his head like a fine rug, his eyes were crinkly, and I liked him immediately.

“I’m sorry.” I sniffled, dabbing at my eyes in a hurry. “My French’s awful.”

“Ah. No problem. Then Anglais we speak.” His smile broadened. “But not very good in it, me.”

“Better than my French, I’m sure.”

“Je m’appelle — my name is Mamadou.” He extended his hand. I found it surprisingly soft. He answered the question my curious gaze asked. “Me, was born in Senegal. I live in Genève now.”

“I’m Dong. James Dong. From the United States.”

“Me, I saw you at Le Seul Oignon. Had I known you was you, I would have met you right there. Did you enjoy Momai Tharam?”

I did not follow this entirely. Then I caught on to his question. He was referring to the chef’s specialty on the menu at the restaurant where we had both dined earlier.

“No, I had the lamb and capsicum curry. It was excellent.”

“Ouo, monsieur! You did not select the chef d’œuvre? That like going to birthday party and not eating birthday cake.”

I laughed, at the same time marveling at how effortlessly I slipped into this easy banter with a perfect stranger; I, who was often wary of my friends. Mamadou steered me across Rue du Mont-Blanc to Willi’s Café, its gleaming black and silver storefront standing out in sharp contrast with the rest of the stately old stone buildings. We seated ourselves at one of the tables on the sidewalk, a hallmark of eateries in European cities. I leaned back in the comfortable tan-colored faux-rattan chair as the waitress approached. Mamadou looked lazy, panther-like, as he lit a cigarette.

“Try a Swiss wine, oui, Monsieur Dong?” Mamadou asked. I became intrigued. I associated vineyards with the lush warm climes of Spain, Portugal, Italy, the south of France, and my very own California. I had no clue grapes could grow so high up in the mountains. I settled on a Pinot Noir de Genève while Mamadou chose the Pinot Blanc de Genève. We watched the throngs of humanity glide past us towards the bridge, Pont du Mont-Blanc, where the River Rhône gives its wistful and melancholy goodbye kiss to Lake Geneva. From the bridge they could gaze at the Jet d’Eau, the world’s tallest fountain, shooting into the atmosphere with an amazing velocity — 130 miles per hour and up to 450 feet high, they said. In the distance, the stately silver-topped crown of the country’s highest peak, Mont Blanc, kept its protective eye on the lake and the city.

The passers-by came in all sizes, appearances and color. I had no way of saying whether they were tourists or locals. They in turn would have thought me Chinese; it was only when I opened my mouth that my accent branded me a Yankee Doodle Dandy. A group of dark young men with wavy blue-black hair glanced at us curiously and politely nodded at Mamadou as they glided by.

“Tamils from Sri Lanka,” Mamadou commented. “They fled from there to here, escaped themselves from the long, cruel war on their island. Genève still offers refuge.”

If I hadn’t tramped around the city, I wouldn’t have known what he meant. After stumbling on a monument emblazoned with the words, “Geneva, City of Refuge,” I discovered this city had historically taken in all kinds of exiles. When Geneva became a bastion for the Protestant movement (Calvin thundered from the pulpit of the Cathédrale St-Pierre in the 16th century), French and Italian Protestants scurried here to escape the flames of imperial and papal wrath. The city sheltered political refugees down the years; Lenin lived here in exile, as did these nameless Sri Lankans of today. I wondered if I should join their ranks. The Red Cross as good as told me a job in their headquarters was mine for the taking.

But what was I trying to escape from? From Elyse? A few years had elapsed since our marriage disintegrated. She suddenly resurfaced, attempting to get in touch with me again. We may not be married now and we’ve been through very difficult times but there’s no reason we cannot be friends — that was the crux of the many messages she left on my voicemail. I steadfastly ignored her overtures. Wasn’t divorce the equivalent of goodbye? The court had been clear-cut and fair in its judgment. She had accepted the court’s decision as readily as I did. So why wasn’t she abiding by it?

Was Mamadou also running away from something? He sounded wistful about Momai Tharam, his exotic dinner in the Indian restaurant, about how much the onions in the gravy reminded him of Yassa Poulet, a chicken entrée from his native Senegal that also used a rich and spicy sauce of sautéed onions.

My mind only half-followed his commentary. I hadn’t been so relaxed in years, and it wasn’t just because of the Swiss wine. After my divorce, my social life had gone the way of the dinosaurs. I discovered I didn’t have a single friend (in California, at least) who wasn’t also a friend of my ex-wife.

Elyse and I had frequented the restaurants along the southern California coast with our friends, from Coronado Island and the San Diego beaches up to Del Mar, Encinitas and Carlsbad. We’d watch the glowing red sun dissolve into the Pacific, and its robust fire never failed to transfer itself from the waters of the ocean into the waters of our margaritas. After the divorce, our friends found it awkward to meet with just one of us without inviting the other. So they met with neither.

Recently Elyse had started calling me, to see how life was treating me, to check if we could visit again as friends. I didn’t buy that. Oh baby, wasn’t a firm goodbye — a forever goodbye — the foundation of a divorce? Did she think I’d turn into a basket case without her? Thank God my home phone and cell phone identified callers. I never picked up her calls, leaving her to deal with my disembodied presence, Voicemail. I wondered why she didn’t use a public telephone where I wouldn’t recognize the caller’s number, or a restricted phone line where the number wouldn’t show up. It may not have entered her noggin that I’d deliberately ignore her calls.

I remained a loner. I lacked the inclination (or the time, for that matter) to nurture new friendships. Mamadou scarcely qualified as a friend but I had taken a great liking to him, and sitting here together in a café bar as the sun went down enveloped me in the aching shadows of déjà vu.

Without warning, Mamadou leaned forward and intoned with an air of mystery, “Rue des Delices. 9 o’clock.”

“What?”

“You meet mademoiselle outside the Institut et Musée Voltaire. Me, if I were you, would not keep dear mademoiselle waiting. ” Mamadou gave me a broad smile and a big naughty wink, and permitted a thin stream of cigarette smoke to snake its way out of his mouth. He grinned again and said, “Ouo, Monsieur Dong, don’t let her be waiting and waiting. You won’t. I know it to be so. You be a real, true gentleman.”

What was he blabbering about? He hadn’t yet drunk enough wine to mess up his brain. Were the Senagalese like the Chinese hampered (or blessed) with a low tolerance to alcohol? I was shaken. Had Mamadou read my mind while I reminisced? Was he well versed in voodoo or hoodoo or whatever black art they practiced in Senegal? Did he know about my divorce? And what would Elyse think if she heard what he’d said? But then, why should I care? Elyse wasn’t part of my life any more.

Mamadou changed gears and asked me my plans for the rest of my stay. I replied truthfully that I didn’t really know, that I formed my schedule as each day unfolded. But tomorrow — my last day in this city — I hoped to once again climb the tower of the Cathédrale St-Pierre. The high balconies had overwhelmed me with panoramic views of Geneva, the lake, and the mountains in the morning. I wanted to feast my eyes again, this time around sunset, before the cathedral closed for the day.

“Coffee, monsieur?”

A tall brunette with a green apron stepped from behind a wooden kiosk on wheels at a corner of Cour de St. Pierre, the courtyard in front of the cathedral, and gestured invitingly. A chill evening breeze had blown away the warmth of the day. A cup of hot coffee sounded good. I asked for a small cup of mocha but the lady kindly gave me a large one at no extra charge.

As I sipped my beverage, I once again marveled at the grotesque appearance of the cathedral. It must have been beautiful when they built it a millennium ago but they had later tacked on extensions which were in sharp variance from the original architecture as though each century wanted to put its stamp and be one up on the handiwork of their forefathers. The resulting hodge-podge outdid the most surreal of Dali’s paintings. For crying out loud, the two towers didn’t even match; one brownish-grey and ornate, the other white and very much a plain cousin to its fellow. They made for an odd contrast but at least didn’t clash. That couldn’t be said of the odious spire that stuck out between them; it was slim and a ghastly green, the kind one sees on tarnished copper. The cathedral itself was neither square nor round or rectangular, bulging in the oddest spots with the many stubby appendage add-ons. Scaffolding obscured part of the building, sturdy metal pipes draped off by tarpaulins, as though the insult to the injury were set to continue.

The coffee rejuvenated me to a giddy high and I bounded up the steps to the wooden doors. The interior of the cathedral had been tampered with as extensively as the exterior. When the Protestant Reform swept across Europe, Calvin and his followers had stripped the cathedral bare, destroying the altar, statues, paintings, sculptures and even furniture considered too ornate. Succeeding generations enshrined Calvin’s spare wooden chair at one side of the nave like a throne. Looking at the high domed ceiling and all around and seeing everything so bare, I felt I was crawling in a mammoth stone cellar, or inside a giant egg staring up at the gray eggshell. Even the sanctuary remained as stark as bleached bone but for the stained glass windows. Maybe God could be felt through stark simplicity as well as through the wonders of His creation, but the barren cathedral had got on the nerves of this divorced Catholic and I was glad to ascend the tower to get the fresh, pure Alpine air from up high.

The spiral stone staircase of narrow never-ending steps (a hundred and fifty, two hundred, more?) was wrapped around a cylinder of gray rock wide enough for just one individual to ascend or descend. A grossly obese person could well have gotten stuck at one of the narrow points. But the medieval now blended with the modern. On the wall beside the stone archway leading to each of the small flight of steps that made up the staircase, a light alternated between red and green, with briefings tacked on a plastic plaque: Attendez! Wait! Warten! (for the red light, when it came on); Montez! Go up! Aufstieg Frie! (for the green). If people followed the instructions, those descending the stairs would not collide against those ascending. If only life had such clear directives, we might have no divorces, no unnecessary and painful farewells.

The stairs led to a central area with stone floors covered with wooden decks. Signs directed the now-weary visitors to various balconies around the tower. The breath heaved out of me, but boy, was I glad I’d made the effort again. The red and grey roofs on the white buildings were more charming when swathed by rich orange light, and as I gazed at the Jet d’Eau, I could have sworn I saw a shimmering rainbow, the colors in its arc blurred, one fusing into the other.

But I had never felt so stiff and cold in my life, with darkness surrounding me. I was a worm in a cocoon. Hearing and sensing the sheath of the cocoon flapping above me, I flailed my arms about, desperate to break out. Then I noticed the faintest sliver of light, just a crack, on my right. I rolled towards it. The sheath was not completely tethered to the hard stone floor, and after a few awkward efforts I forced my body to wiggle and squirm through the opening.

I realized I must have passed out, and had “come to,” several hours later. Something had knocked me out.

I rose unsteadily, my legs wobbly. The moon, almost full, was steadier in the sky than I was right now. Many strained moments later, my throbbing head figured out that I stood on one of the balconies of the cathedral, and it was night. How? Why? I remembered lingering on although others glanced at their watches and descended the stairs as closing time neared. I hovered above Geneva, enraptured by the hues of the sunset bathing the city and the lake. As people left, I treated myself to virtually a private view, the kind that usually cost megabucks. I reveled in it. But I could not remember leaving the cathedral and reentering it after sunset or even entertaining such an idea.

As I tottered, holding on to the parapet with one numb hand, I inhaled a slow, long draft of the cold night air at a sight I never expected to see and that few saw from this vantage point — the panorama of Geneva by moonlight. Nobody could get up here by night. Why was I here? The colors of the buildings and rooftops had all faded to blend with the black and silver scheme, and the lake scintillated under the moon, and Mont Blanc now truly became its name, White Mountain. But how and why was I here to be able to see this? What was the mystery of my perspective?

A sudden gust of wind hit me hard as I groped along the wall and entered the central portion of the tower. I wanted to go to the next balcony and get a different view as I tried to work out what had happened to me. It was pitch dark inside on the wooden deck, but for the soft moonlight streaming in from each balcony entrance. While climbing the stairs, I hadn’t noticed they were lit by electric lights, hadn’t thought that in medieval times a person would carry a candle or a burning torch to light the way. And woe if one ascended the spiral staircase while another was descending. I startled myself when a floorboard squeaked under me, quite loudly too, but I pressed on.

When I reached the next balcony, I heard a soft footfall behind me. By the time I turned, the man was almost upon me. He was squat and muscular, his hair so closely cropped his skull looked clean shaven, his disproportionately long arms dangling out of his torso. He lunged at me, a bull ape gone amok. I froze, every heart beat distorted into a sickly shudder. He managed to grab my shoulder and swivel me, locking his forearm around my neck, tightening his stranglehold as he rocked forwards and back on the balls of his feet. The walls and the eaves of the cathedral swung in wide arcs, keeping perfect time with our tense swaying. The breath was squeezed out of me and pressure mounted in my head, concentrated behind my eyeballs. A cross that jutted out from a turret on the roof bloated and blurred into a menacing gargoyle, reverting to a cross again when my attacker’s hold momentarily eased.

Earlier that evening I came face to face with the green cathedral spire from a few feet away across a chasm between my balcony and the spire. The wind and weather had worn down the green paint on the spire exposing little patches of the underlying black stone, too small to be seen from the ground below but contributing to the discolored copper appearance. All it needed was a little tender loving care, some patchwork paint. The spire was a bell tower; many great big bells hung silently in a circle from a round beam in a chamber within.

I thought of those bells as, with a superhuman burst of energy — truly superhuman, in my condition — I broke my assailant’s lock and jumped forward as far as I could before I turned to face him on unsteady feet. Had we been in the bell tower, I’d have summoned every ounce of strength and rung the bells — dong! dong! dong! — my liberty bells, arousing the sleeping city, letting its people know of my predicament — for whom do the bells toll? They toll for me …dong! dong! — or at the very least, the bells would signal that something horrible and out of the ordinary was taking place.

My assailant charged. So far he had uttered not a word, as though he were a mute. He only let out steamy grunts which unnerved me. I sidestepped his bull rush but he had anticipated me and he socked my jaw with a well-placed punch and sent me crashing against the wall, where I reeled and slumped down to the floor with a moan. Earlier that day I’d compared the high dome of the cathedral to an eggshell. Sepulcher was more like it.

My insides tore themselves out, urging me to scream, and scream again and again, but my throat was as dry as a withered parchment. Besides, who’d hear me? Down below in the square, the Cour de Saint Pierre, there were no residences. A stately building across from the cathedral housed the Departments of Finance and Public Instruction. A café and some antique shops stood at one side of the square, as did a psychiatrist’s office. In the old days when psychiatry was looked upon as the satanic branch of medicine, psychiatrists offered consultations at night, their patients skulking down the darkened streets, wrapped in thick cloaks and carrying measly hand lanterns dispensing fuzzy light. Those days were long gone.

There was no one to hear me and I could not scream. Only moan, a little more piteously whenever the man’s boot crashed into my side, cracking yet another rib. For the first time, the naked fear of death gripped me. This man, whoever he was and for whatever reason, intended to kill me. Had anybody been murdered in a cathedral since Thomas Becket was butchered in the nave of Canterbury cathedral by the bloodthirsty knights of Henry II? If not, the honors would go to me, James Dong of California, put to death for reasons unknown on the high balcony of the north tower of the Cathédrale St-Pierre. But I had no time to dwell on the bizarre and unbelievable nature of the circumstance, for my assailant’s boot came down hard on the middle of my face and I understood what “excruciating pain” was as my nose broke and the blood gushed out to form warm, sticky splotches on the cold slate stone. And the stars I saw right then weren’t the ones in the sky.

Nothing happened, although minute after minute slipped by. I could sense my assailant standing over me, his eyes boring into my broken frame. He scooped me in his arms and before I knew it, he tossed me over the parapet as if I were as light as a sack of feathers. Any doubts that this bastard lacked the ability to speak vanished. His sardonic chuckle and his sinister, jubilant whisper propelled me on my way down.

“Adieu, monsieur.”

I plummeted earthward with the same velocity with which the Jet d’Eau shot heavenwards. The wind whistled around me on my journey to – wherever. Myriad thoughts spliced through what would be the last few moments of my life. I shrieked an appeal to St. Francis and St. Teresa, then remembered in horror that this was the Protestant bastion from where Calvin and Knox thundered their dissident sermons, and got mighty confused and just appealed to God as the Holy Ghost and to Christ. I thought of the discovery of my corpse when the sun rose. My body would be a mangle of flesh and sinew and tissue, cloth and blood and bone, all mulched and smooshed beyond recognition on the cobblestones of old Geneva. Would they be able to identify me? My pockets felt empty; my wallet and business cards had been removed, my passport locked in a burglar-proof safe in my hotel. Elyse’s face swam before me, with those big eyes flanking a petite nose, and I heard her voice on my telephone answering machine: Jimmy, Jimmy, can’t we be friends? Just friends?

Yes, I wanted to answer, yes! yes! yes! Can you forgive me for being so pig-headed?

Now I can convey these sentiments to her, but I must figure out the most painless way to do so. Geneva is a city of international diplomacy yet none of her diplomats, greenhorns or veterans, can teach me the best method of going about this. Some stuff you have to work out yourself.

Many things remain a blur, and more have been blotted out of my memory, perhaps for good. But I clearly remember my conversation with an officer from Interpol, Marcel Renault. I have forgotten his title, which is why I just think of him as “The Super Cop.” I recollect the discussion as much for the setting as for the content. We sat, not across a table from each other in some sterile, forbidding police station, but side by side on a bench in one of the city’s sprawling parks, the Parc La Grange on the south shore of Lake Geneva. The rolling lawns, shady trees with every hue of green from the subdued to the vibrant and the light to the dark, and the bushes with the crimson and lavender flowers helped me relax, even in the company of a super cop.

Yes, one of those ugly extensions to the original cathedral I had sneered at had been my savior. A dinky little ledge, but had it not been there, I’d have plunged headlong to the ground. I resolved to look hard at things I had considered despicable or unworthy in some way or the other, to reevaluate them.

“I can’t tell you too much, at least right now while our investigations are ongoing,” Renault said. What little he told me was amazing enough. Indeed, I had become unwittingly involved in a crime ring operating in several countries that used Geneva as a conduit for passing messages.

“A clever operation. The gang member assigned to receive instructions came to the junction of Rue Chaponnière and Rue du Mont-Blanc on certain days when an old lady sang. Most people just passed by, or stood listening for a while. But the gang member stood there for a long time, pretended to be absorbed, and that’s how the accomplice who passed the message identified him.”

“And the accomplice was ….?” I tailed off, dreading the answer.

“Mamadou Mbaye. A nice young man. I trust you had an enjoyable hour sipping wine with him at Willi’s, Monsieur Dong.”

Without those few steel wires holding it in place, my jaw would have disengaged itself out of my skull. Renault’s razor-thin smile showed he’d expected my reaction.

“I was right there, sitting on a bench on Rue du Mont-Blanc in a vantage position, watching the two of you. After much hard work, we finally caught on to their modus operandi. The singer — Frau Rudolphina Kropf-Zuber — is blind. She can’t tell who passes by, who stands before her. But every scheme has a flaw. Mamadou Mbaye looked only for a person who on a certain day at a certain time stood listening to Frau Kropf-Zuber at the same spot. You, Monsieur, happened to be entranced by her rendition of “Edelweiss” just a few minutes before the actual gang member arrived.”

“And …?” I couldn’t say much, only speak a limited number of words before pain forced me to stop. They had patched up my face, jaws and body. It would take time before I became whole again.

“You threw everybody off. The gang panicked when its message was delivered to the wrong person. Mbaye was an innocent pawn. We, that is, the Swiss police working with Interpol, took him into custody shortly after he met with you. He had no clue how he was being used. He thought he passed along messages to lonely people looking for a little love — recherche de l’amour. That he helped out with ‘affairs of the heart’ and was paid handsomely for it. But there were no beautiful ladies waiting eagerly on quiet lanes. It was all in code.”

I nodded. Mamadou hadn’t been as clairvoyant as I’d thought. I carried Elyse’s ghost with me, a spook painting my thoughts, so much that I unreasonably assumed others, even perfect strangers, were conscious of my haunting and reacted accordingly.

“But why?” I asked, speaking through clenched teeth and pausing between words because of the pain. But pain or no pain, the question begged to be asked. “Why hurl me from a cathedral tower? It’s so easy to kill. A simple gunshot, a quick slip of a knife between the ribs…”

Renault spread out his hands, then brought his palms together in a steeple, cementing his chin on its tip. “I don’t know. I might, eventually. Right now, I’m guessing they panicked. They either suspected or knew we were on to them. Mbaye gave out the coded message to some unknown person — it could have been a policeman. You told Mbaye you would leave Geneva in a day. They had no time to find out who you were, where you stayed. The one thing they knew was that you planned on visiting the cathedral the following evening to see the sunset. That was their last chance. There’s no regular coffee kiosk there. They set one up to snare you and dope you. A gang member shadowed you all the time in the cathedral, and pulled you under that canvas sheet. Unluckily for you, most of the tourists must have left by then.”

“And the gangster came back at night.”

“No, he stayed in the building. This cathedral’s been around from the 12th century but it has some modern features. Electric lights, a red-green traffic light system to regulate people on the stairs, and so on. And every evening the doors are secured with an alarm system.”

“Why didn’t he finish the job while I was doped?”

“Again, I can only guess. Maybe the drug’s effect wore off too soon. Or they wanted more time to investigate who you were and asked your killer to hold off until he got their final instructions.”

“But how could the person carrying such instructions enter the cathedral bypassing the alarm system?”

Renault ran a finger across his cheek and solemnly said, “Monsieur, we have a very useful invention that sends messages across the best electronic security barriers: the mobile phone.”

A blush warmed my face as Renault went on, “An early morning walker caught sight of your red shirt halfway up the building. We nabbed your would-be killer before the cathedral opened. The church authorities were — what’s the word? Let me think, ‘mortified’ ? Yes, they were mortified. They are quite efficient in shooing out the tourists at closing time and checking nobody is inside before they lock up, but of course they don’t think to look out for somebody who hides deliberately. And the cathedral has so many hiding places.”

We sat for some time, and I rested my eyes on the greenery.

“I hope you recover quickly from this terrible experience, that your next visit to Geneva will be more relaxing.”

“I will never come here again.”

“I hope those are the sentiments of the moment, Monsieur,” Renault said. “You have many friends and well wishers in this city, most of them anonymous. I was part of the Interpol team investigating the horrible Mumbai terrorist attack on the railway station, the hotel, Café Leopold, the Jewish Center … and I remember Western tourists being asked in an interview if they would ever visit India again. They emphatically said: Yes! Indians, total strangers, showered them with so much concern and hospitality that they were really touched. Some of the Indian hotel staff quickly moved them to safer areas in the building, and later many of those staff were found dead — killed by the terrorists. They had sacrificed their lives for the European tourists. Ultimate definition of ‘hospitality.’ Likewise, the good souls of Geneva were stunned when the news of your near-murder became known. Thousands prayed for you and sent money to the cathedral, the police and to the hospital to pay your medical bills. A few francs here, a few francs there. This is one of the most crime-free cities in the world. Oh, we have the petty crimes — at the Gare d’Cornavin, the pickpockets, mostly drifters from Eastern Europe or North Africa who hang around the railway station. But very few serious crimes. So something like this, it’s — it shocked the people.”

When I did not respond, he continued, “I know. You want to leave, never to come back. But do you know there are two kinds of goodbye? In French, we have a word for each. There’s adieu. That’s the final goodbye, when you part with somebody and never expect to see that person again. It translates as ‘to God.’ The other is au revoir, a shortened form of au plaisir de vous revoir — I do so look forward to the pleasure of meeting you once more. Or, as you Americans say, ‘See you later.’ ”

I still said nothing. Then he said, “Pardon if I intrude on anything personal, but may I ask about the name Eloise, if it means something to you?”

He hit the spot here, and I blushed again, more strongly. He noticed, but without as much as a shake of his eyelid, said smoothly, “No matter, no matter. This name you constantly recited in your deliriums. A time came when the doctors thought they would lose you, and they were concerned if this Eloise was somebody to be contacted urgently.”

There was so much re-thinking to do. I mulled over the offer from the Red Cross. I had never been seriously ill in my life, to the delight of my health insurance company which enriched itself on the premiums I paid without having to do a thing in return. Here, for the first time, I felt the reassuring touch of a nurse’s hand on my forehead, and the solace of an intravenous drip nourishing me through my veins when my mouth would not open.

The job offer from the Red Cross was a desk job, similar to the service I’d offered them as a consultant. But I now had a personal sense of appreciation of what the Red Cross did in the field, often in parts of the world with none of the resources we Americans took for granted. War surgery in the dirt amid the explosions of bombs and the hiss of flying shrapnel, ensuring clean water and food supplies for civilians in battle zones, combating tuberculosis and AIDS in villages broiling in unheard-of ovens, sticking up for soldiers disabled in wars and cast aside like spent bullets by their heartless governments ….

Perhaps I would accept the Red Cross’s offer, live in the City of Refuge, and work like crazy to help make these things happen. Elyse could visit me here. As a friend. A good friend. Or something more? Heck, I now had many unknown friends in Geneva who had prayed for me, and dug into their wallets and pocketbooks to help out. I didn’t even know what any of them looked like. Well, at least I knew one friendly face.

“Mamadou. Is he all right?”

“Yes, he is. And he’s cooperating fully with us.”

“Can I meet him? Maybe I’ll run into him at Le Seul Oignon.”

“His favorite restaurant. In the normal situation, you would. But for his own safety, we have taken him elsewhere for a little while.”

“Where?”

“Where nobody would think of looking for him. Well, monsieur, have a restful time for the rest of your stay in Geneva. You should take a boat cruise. You know, in a house overlooking this very lake Mary Shelley wrote ‘Frankenstein.’ You can see the house from the lake.”

“I had a Frankenstein experience. I don’t need to see the house.”

We laughed and rose, taking that as a parting cue.

“So will we see you in Geneva again sometime in the future?”

I looked Renault in the eye. He knew my answer but I replied anyway.

“Yes,” I said, softly. “Au revoir.”

Vishwas R. Gaitonde spent his formative years in India, has lived in Britain, and now resides in the United States. His writings have been published in those countries, and elsewhere. His literary distinctions include two writing residencies at The Anderson Center (United States); a Summer Literary Seminars fellowship (Canada); and the Hawthornden Castle International Writers Fellowship (Scotland). His short stories and essays have appeared in literary magazines such as Iowa Review, Bellevue Literary Review, Santa Monica Review, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Mid-American Review, and Kweli. One of those stories was cited as a Distinguished Story in Best American Short Stories of 2016. His journalism credits include The San Diego Union Tribune (CA), The Hartford Courant (CT), The Cedar Rapids Gazette (IA), The Adelaide Independent Weekly (Australia), and The Hindu, Serenade, and Scroll (all India). Twitter: @weareji

Staff Essay Poems Satire Short Story

About

Omnium Gatherum Quarterly (OGQ) is an invitational online quarterly magazine of prose and poetry, founded in 2019 as part of the 50th Anniversary of the Community of Writers. OGQ seeks to feature works first written in, found during, or inspired by the week in the valley. Only work selected from our alums and teaching staff will appear here. Conceived and edited by Andrew Tonkovich. Submissions will not be considered.

Editor

Andrew Tonkovich edits the West Coast literary journal Santa Monica Review and hosts Bibliocracy, a weekly books show on Pacifica Radio KPFK in Southern California. His most recent essays, short stories and reviews appear in the OC Weekly, Los Angeles Review of Books, Orange Coast Review, Faultline, ZYZZYVA and Ecotone. He is the co-editor, with Lisa Alvarez, of the first-ever literary anthology of writing from and about Orange County, California. Published by Heyday, Orange County: A Literary Field Guide includes contributions from writers who have taught in or attended the Community of Writers poetry and fiction workshops, including founder Oakley Hall.