EDITOR’S NOTE

By Andrew Tonkovich

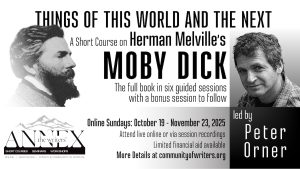

Thanks for reading the final 2025 issue of the Community of Writers’ in-house, invitation-only journal, where we find our shared struggles documented and, happily, our successes celebrated. In addition to featuring new work, I’m happy to reprint a profile of one of our most esteemed alums written, naturally, by another alum. There’s autobiography, poetry, a full-length short play, and meditations on stories, storytelling, and publishing from participants and teaching staff. Finally, we get a real-time dispatch from a participant of Peter Orner’s incredible online short course on Moby Dick from the Writers Annex: Things of this World and the Next.. This is an eclectic, diverse, and active community. Please do share the OGQ toward celebrating your own membership and inviting others in!

Andrew Tonkovich

Editor, OGQ

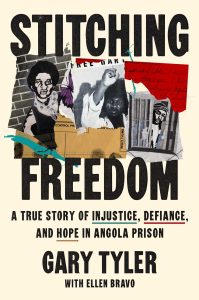

THE STORY BEHIND STITCHING FREEDOM

By Ellen Bravo

I first heard about Gary Tyler in early 1976, when I read his “Letter from Death Row” in the Southern Patriot. In October of 1974, Gary had been on a bus packed with Black students being sent home from a white school. The bus had to make its way through a mob throwing rocks and bottles and screaming racist epithets. Someone fired a shot at the vehicle; a white youth in the crowd was hit. “Everyone involved in the stoning of the school bus should have been arrested as accessories to the crime,” Gary wrote in that letter. “This includes the authorities, since they did nothing to stop the attacks.” Instead, the police framed Gary for the murder. An all-white jury convicted him. The teenager was shipped off to death row at Angola State Penitentiary, a former slave plantation notorious for violence and harsh conditions.

That summer, my husband and I traveled to New Orleans to march with two thousand others to “Free Gary Tyler.”

Through the years, we tried to keep up with news about his case. We learned the Supreme Court had overturned the Louisiana statute that required the death sentence for certain crimes. The same judge who presided over Gary’s trial resentenced him to life without parole. Despite national and international support from people like Rosa Parks, Gil Scott-Heron, and Amnesty International, Gary wound up spending more than four decades at Angola before another Supreme Court decision led to his release in 2016.

A few years ago, I met the couple Gary lived with in Pasadena, California, those first months of freedom. I learned he really wanted to write a memoir but had to work full-time – the pennies inmates “earn” at Angola don’t go toward Social Security. In my years of organizing, I’d often helped workers tell their stories in their own words, using prompts and editing and fast typing. Gary and I met in March 2023 to explore this option. We began a series of weekly calls and occasional visits that resulted in Stitching Freedom: A True Story of Injustice, Defiance and Hope.

A few years ago, I met the couple Gary lived with in Pasadena, California, those first months of freedom. I learned he really wanted to write a memoir but had to work full-time – the pennies inmates “earn” at Angola don’t go toward Social Security. In my years of organizing, I’d often helped workers tell their stories in their own words, using prompts and editing and fast typing. Gary and I met in March 2023 to explore this option. We began a series of weekly calls and occasional visits that resulted in Stitching Freedom: A True Story of Injustice, Defiance and Hope.

And what a story it is. Most of it I had never known.

Why did the police pick Gary? Because he’d spoken up that day when officers harassed another student. The original charge was “disturbing the peace.” At the station five officers beat him savagely within earshot of a group of mothers – including Gary’s – waiting to pick up their children. The police were trying to get him to confess. He refused.

I learned that a group of politically active prisoners at Angola became Gary’s guardians and mentors. Among other things, they urged him to write “Letter from Death Row” by giving him books, a dictionary, and feedback on each draft. They helped him understand that what had happened to him was part of a system of oppression. When Gary got sent to the dungeon, people like Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace, who’d become members of the Black Panther Party in prison, arranged to spend time there, to let him and everyone else know they had his back. In addition to teaching him about organizing, his mentors helped Gary maintain his spirit and his humanity. “Don’t let the puppet master get inside your head,” Wallace told him. Gary realized he had a responsibility to those who were fighting for him to stay strong. “Me and bitterness had become real good friends,” he told me, and he worked hard to overcome that.

During those hours with Gary, I learned how he filled his time with purpose. Once he arrived in the main prison after nearly nine years in solitary confinement, he continued reading and fought for the right to an education for himself and others. He became involved in the prison Drama Club and was president for twenty-eight years. He also became a powerlifting champion, a hospice volunteer, and a magnificent quilt artist – and a mentor to many inmates.

a mentor to many inmates.

Once free, Gary’s schedule didn’t leave time to write, but he certainly had storytelling skills. He’d learned a lot all those years in the drama club, where he wrote and directed plays. He also had pages and pages of notes written in prison, an extraordinary memory, and a New Orleans lawyer with an extensive archive.

From the start, Gary knew the goals for his book. He was eager to show he’s not just a “tragic story,” but an example of how humans can triumph over injustice. At a time of book banning and efforts to whitewash American history, he wanted to lay out his experience and help disrupt the playbook of division that benefits those with power and money. And he wanted to express gratitude – to his amazing family, his legal team, to all who chanted “Free Gary Tyler!” throughout the years, and to those today standing up to inequality and hatred.

Stitching Freedom: A True Story of Injustice, Defiance and Hope is available here or wherever books are sold.

COMING UP FOR AIR

By Meriwether Clarke

Daisies in May take long, slow

breaths. They do not

over-exert themselves, waiting

for water.

Nearby, dried leaves wear

sun like a tattered shawl.

Mornings are still cloudy.

Nurses walk to work

in scarves.

The windows of this house are open

and I pray

neighbors sleep when I

creep outside to pick bouquets

of yellow and orange.

My hair is so

long it drags

on the ground unless worn

braided and looped

around my neck.

Some days, the flower pots are full

and some days they are empty.

When I die,

I hope my body blossoms

within such a vessel, inside earth

but not beneath it.

A Note on Finding Yourself at the End of the World

Between the two Trump administrations, I wrote a chapbook of poems about the Greek mythical figure Persephone. Living through a deadly pandemic made me think, albeit momentarily, that perhaps I was an expert on what it felt like to be trapped, surrounded by death. But a lack of familiarity with my chosen topic soon became clear. When I attempted to order the poems into a cohesive manuscript, it was impossible to ignore that the project was a failure. This wasn’t particularly hard to accept. Vaccine shots in my arm, my loved ones still blessedly alive, I wanted to celebrate—I was done thinking about loss.

Like most of this country, I decided mass death was a boring topic far too soon. It’s undeniable that there was no national reckoning or institutional mourning for the hundreds of thousands of people who died during the peak of the pandemic, the over three hundred people a week that are still dying[1], because of politics. But the American ethos is also one of constant reinvention. We are a population shaped by a cultural lexicon of dreamers, drifters, and hustlers; a people always trying to get ahead, applying whatever collective amnesia is necessary to do so.

Lately, that American tendency to forget is more omnipresent than usual. With competing versions of basic facts, and even lived history, swirling across our phones, the forward movement of time feels distorted and difficult to track. This is another mass death of sorts, a metaphorical one—a death of order, of chronology, of what constitutes truth.

It is, to say the least, deeply disorienting. But, while American politics is a dizzying, distracting show, populated by sycophants and psychopaths, the hours still move forward. The Earth continues to warm. I think about fires and floods too much. My grandmother survives a devastating stroke and re-learns to talk. The vet tells me that my once young cat now qualifies as a senior. My country elects a rapist. Again.

Like many other English speakers, I discovered the novel I Who Have Never Known Men earlier this year. Published by the late Belgian author Jacqueline Harpman in 1995, the novel captures something of the feelings I have tried to describe above, characterized by Carmen Marie Machado in The New Yorker as the experience of “finding yourself at the end of the world.”[2]

The protagonist is an unnamed woman retelling her life story before she dies. She describes almost the entirety of her childhood as occurring alongside 39 grown women, trapped in an underground cage policed by a handful of male guards. Unlike her fellow prisoners, she has no memory of life before this entrapment.

A third of the way into her tale, a loud siren goes off and the guards scatter, one of them dropping his keys as he runs. They fall just within reach of the bars, a lucky twist of fate that allows the narrator and her fellow prisoners to escape. Above ground, they find ample stores of food, basic medicines, and other cells like theirs (filled with the rotting corpses of prisoners who were far less fortunate), but no other living people. The land around them is mostly barren and rocky. They have been dropped into a world they have no context for, but they make do, building rudimentary homes, forming romantic relationships, and re-learning how to live.

As the youngest of the group, the narrator knows she will be the last of the women to survive. This place of utter isolation is where the reader finds her at both the novel’s beginning and its conclusion. But in between, we follow her strange coming of age among a disquieting, eerie post-apocalyptic landscape, one where she must define truth for herself in the absence of anything like shared memory.

Central to the protagonist’s slow reckoning with her own humanity is her recognition of time. Before the women’s escape, she creates a basic timekeeping system through counting her own heartbeats. The act is one of rebellion and self-preservation. Moments of self-definition, like this, are the only sort of resolution the reader receives. We never find out what triggered the siren, or even why the women were imprisoned in the first place. There is no tidy wrapping up of history, no glossy heroes arriving on horseback, no savior, no rescue.

Sometimes, lying in bed, I feel my own pulse, ticking just beneath my jaw. When I am awake, everything feels at once hurried and slow. I speak of things using dates and calendars, but these tools fail to capture what it feels like, right now, to be alive, or what, in this most perilous of moments, we should use to measure our hours. In four-year increments? In the seconds it takes to type a tweet? In the blink-and-you-miss-it bang of a bullet ending someone’s life at a supermarket or a school? In the three staccato syllables of you’re fired?

I don’t know the answers to these questions. But I do know, as Persephone’s plight resulted in, that soon it will be winter, and then spring, and then, somehow, another summer. Many of the trees here in California will shed their leaves, but many will keep them. Outside my window, beside the small table where I sometimes eat meals, is my grandmother’s patio. I will watch it drink in the sun on hot days, and I will watch water coat it during the rare rainstorm. I am not underground, not yet, and for that, at least, I am grateful.

[1] This figure was released by the CDC in May, before the mass resignations, layoffs, and firing of the agency’s director in August 2025.

[2] Machado, Carmen Maria. “‘I Who Have Never Known Men’ Is a Warning.” The New Yorker, 5 Sept. 2025.

Meriwether Clarke’s poetry has appeared in Best New Poets, Colorado Review, Prairie Schooner, Poetry Daily, The Rumpus, Cimarron Review, Seneca Review, The Journal, Sixth Finch, and elsewhere.

A graduate of UC Irvine’s Programs in Writing and Northwestern University, she has been supported by the Vermont Studio Center, the Community of Writers, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Her chapbook, twenty-first century woman, was released by Dancing Girl Press in 2019. Her debut full-length collection, Body Memory, was released by Unsolicited Press in 2025. She currently lives in Santa Barbara, California.

BROTHELS, WILDFIRES, AND CASINO BALLROOMS: ON FOREGROUNDING COMPELLING SETTINGS

by AnnElise Hatjakes

I grew up in Reno, Nevada and spent my childhood playing “The Floor Is Lava” on elaborately patterned casino carpets. In high school, I played Texas Hold ‘Em poker in my friend’s basement, daydreaming of when I might compete at the World Series of Poker. My undergraduate years were soggy ones spent drinking malt liquor in back alleys before singing Johnny Cash songs at the West Second Street karaoke bar. When I attended Community of Writers this past summer, I made the familiar drive up to Lake Tahoe and was struck by how much of the landscape changes over the course of that one-hour drive.

I grew up in Reno, Nevada and spent my childhood playing “The Floor Is Lava” on elaborately patterned casino carpets. In high school, I played Texas Hold ‘Em poker in my friend’s basement, daydreaming of when I might compete at the World Series of Poker. My undergraduate years were soggy ones spent drinking malt liquor in back alleys before singing Johnny Cash songs at the West Second Street karaoke bar. When I attended Community of Writers this past summer, I made the familiar drive up to Lake Tahoe and was struck by how much of the landscape changes over the course of that one-hour drive.

None of these settings in Reno and Tahoe—though I knew them best, as they’d become as much a part of me as the sunburn-turned-freckles on my shoulders—made it into my early writing. They felt too familiar. As a local attending the University of Nevada, Reno’s MFA program, I already felt lesser than the students who had been courted from across the country with teaching assistantship funding. It wasn’t until I saw the Biggest Little City through those students’ eyes that I began to think of this setting as being worthy of the page. Even then, my stories were largely setting-less (a bar, a house party, a featureless hike), or the setting was prioritized so much less than other craft elements that it hardly even made an impression as a background presence.

It wasn’t until I moved to Columbia, Missouri, for my PhD program that I started thinking more about the setting of Reno and rural Nevada more deeply. During one of the early getting-to-know-you activities, we talked about where we were from, and I mentioned how the first time I traveled to another city, I was taken aback when I noticed a lack of slot machines in the grocery store. I saw in my fellow students’ surprised expressions that maybe my hometown was more interesting than I’d given it credit.

My critical focus during my doctorate program centered around mythmaking and place. After reading all of the books on my comprehensive exam list, I arrived at the belief that the west was much more than a geographic place. It was an amalgamation of ideas, cultures, and feelings born out of the people who lived there and the land they lived on. In framing my creative dissertation, which was a dual timeline novel about a modern-day historian in Reno, Nevada, and the slain brothel madame she’s studying, I thought a lot about how to describe a place in a way that captures such elusive expansiveness.

My critical focus during my doctorate program centered around mythmaking and place. After reading all of the books on my comprehensive exam list, I arrived at the belief that the west was much more than a geographic place. It was an amalgamation of ideas, cultures, and feelings born out of the people who lived there and the land they lived on. In framing my creative dissertation, which was a dual timeline novel about a modern-day historian in Reno, Nevada, and the slain brothel madame she’s studying, I thought a lot about how to describe a place in a way that captures such elusive expansiveness.

In Rebecca Makkai’s 2023 essay on Literary Hub, she writes, “Setting is, in my view, the most underutilized tool in fiction.” She later argues that as writers, we have unlimited budgets for set designs unlike filmmakers who are often relegated to park benches and coffee shops that are inexpensive to use or recreate. After reading her essay, I thought about how settings can be used as an active part of the story. How can they generate energy that propels the reader forward? How can we utilize this underutilized tool? With those questions in mind, I reflected on the settings of the stories in my forthcoming collection.

The opening story, “Andromeda,” is set at the Moonlite Bunny Ranch and follows a college student whose sexual awakening parallels her experience touring the brothel for a class. In the story, “Fire Season,” a young boy accidentally starts a wildfire while trying to impress a crush. A group of three friends have fun ogling male dancers, not knowing that a jealous ex-boyfriend is en route in “A Male Revue.” In “Horseplay,” readers see a woman at different points in her life trying on different identities at Burning Man.

In all of the stories in my collection, I asked myself whether or not they could be set anywhere aside from where they are. If the answer was “yes,” I reworked the draft. If the answer was “no,” I knew that I had my setting right. Setting for me is more than a craft element; it is a way to honor where I’m from. As the old song goes, “Home means Nevada to me.”

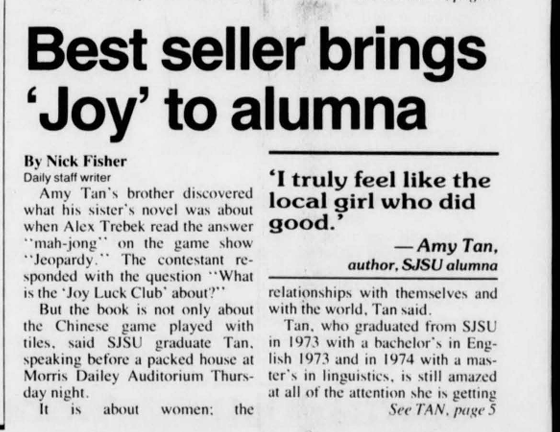

AMY TAN: NOVELIST, BIRDWATCHER, ICON

by Julia Halprin Jackson

Thank you to both Knopf and San Jose State University Magazine for permission to reprint this inspiring conversation between Amy Tan and Julia Halprin Jackson.

Thank you to both Knopf and San Jose State University Magazine for permission to reprint this inspiring conversation between Amy Tan and Julia Halprin Jackson.

Celebrated novelist Amy Tan shares how her love of language blossomed at San José State.

As they flit and fly within arm’s reach of her writing desk at home in Sausalito, Amy Tan counts the species of birds that visit. She’s up to 66 so far.

The award-winning author of the literary classic, The Joy Luck Club, discovered her passion for nature journaling following the 2016 U.S. presidential election, when the weight of the world felt profoundly heavy. So she turned her attention to the sky. Her practice of birdwatching, illustrating and writing, transformed into Tan’s most recent book, The Backyard Bird Chronicles, a collection of journal entries, drawings and observations of life, birds and creativity.

Tan honed her skill for observation as an undergraduate at San José State in the early 1970s. Five decades later, she recalls an important moment in one of her English classes. The late SJSU English Professor Franklin Rogers assigned his class to write down all of the images that came to mind after reading Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Tan, who created her own major with a mix of English and linguistics courses and enrolled in seven classes a semester, found Rogers’ approach refreshing.

“In the case of The Scarlet Letter, the images had a lot to do with light and dark,” says Tan, ’72 English/Linguistics, ’73 MA Applied Linguistics, ’02 Honorary Doctorate. “I remember the emergence of Hester coming out of the dark and walking through the forest, past a row of trees. Even now, I see the shadows of soldier-like trees flitting across her. It was so eye-opening because I realized that’s how I respond to fiction — through subliminal aspects of a scene that were very visual and imagistic. I realized that was a great way to think of writing: Think of images and how they build upon one another and transform. That class at San José State was very instructive to me.”

A finalist for the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award and the International Orange Prize, Tan is the author of seven novels, two memoirs, two books for children and The Backyard Bird Chronicles. Her work has been translated into more than 35 languages. She was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2022 and awarded the National Humanities Medal by former President Joe Biden in 2023. But she couldn’t have predicted this meteoric rise in literary celebrity during her days at SJSU.

Discovering a love for words

When Tan, who was born in Oakland, arrived at SJSU with her then-boyfriend and now husband of 50 years, she envisioned becoming a professor of linguistics. After completing her master’s in linguistics at SJSU, she was accepted to a doctoral program, first at UC Santa Cruz, and later at UC Berkeley. She left academia after the sudden murder of her roommate, who inspired her to shift directions.

“Linguistics is very compatible with being a writer,” she says. “It’s a love of language and how language is used, as well as the imagery, history and sociological import contained in words. It is wonderful.”

Tan’s dexterity with language came in handy when she transitioned out of academia and worked as a freelance business writer, copywriting for industry giants like IBM and AT&T as much as 90 hours a week. It wasn’t until she was on vacation and received a cryptic message that her mother was sick that Tan recognized a core truth: To give her life meaning, she was compelled to write fiction grounded in her own experience, which meant learning more of her mother’s and grandmother’s past.

She traveled to China with her mother and began writing stories in earnest — stories that later laid the groundwork for The Joy Luck Club. The beloved novel tells the stories of Chinese women living in San Francisco and their relationships with their American-born daughters, inviting readers in through an apartment window to watch four families gather to play mahjong and discuss the stock market. Each story plays with time in distinct ways, zooming into a matriarch’s path out of China, and then to one grandmother’s experience living as the fourth wife to a wealthy man. A masterclass in language, character and setting, The Joy Luck Club opened doors Tan never expected.

Seeking emotional truth

When the novel was published in 1989, it spent 40 weeks on The New York Times bestseller list, attracting attention that caught her unprepared. As a woman writing an American novel that centered Chinese American daughters, mothers and grandmothers, Tan felt a sudden and unwanted sense of responsibility.

“I was handed the mantle of responsibility that I didn’t quite know that I could handle,” she says. “I constantly found myself saying, ‘No, this is not representational; this is fiction.’ The book was published during a time when people were trying to find literature that could right the social wrongs that had been [committed] in the past, especially in stereotypes and underrepresentation.

“I had people praising me for writing about their lives, characters that they could identify with, while others said, ‘How dare she write about people speaking broken English? That’s not how we speak in my family.’ But people didn’t understand. There’s no way one book can satisfy the emotional, sociological and psychological needs of many different people from different backgrounds.”

As Tan navigated the international spotlight, she discovered the true pleasure in writing fiction — exploring the universal emotional truths inherent in families, especially between daughters and mothers. Her storytelling paved the way for generations of writers to come.

Following the release of the 2021 PBS documentary, Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir, novelist and former Steinbeck Fellow at San José State, Vanessa Hua, wrote that “Tan inspired me and so many others who followed to write the stories that only we could tell.”

Regardless of the nationality or gender of her characters, Tan wants her readers to know that good storytelling speaks to its readers when it is grounded in specificity — everything from the description of a jade pendant to the color of pygmy nuthatch’s feathered head (slate gray). The connections live in the details.

“Even if the outer appearance of a story is fictional, it has to have depth and an emotional component that’s very true, very authentic,” Tan says. “People believe in that specificity of detail, combined with emotion. It makes them feel that this [the story] is their world that they have inhabited, even if they’ve never been a part of that world. That’s because emotions are universal.”

Watching the right things

Fifty-two years after graduating from SJSU, Tan’s life is guided by curiosity and attention to detail. In order to draw a bird well, she says you must first repeat out loud what you see: Black crown, blue eye ring, short beak. The act of telling creates an image in your mind that you can then better re-create on paper, just as the practice of recalling literary images from a powerful book can strengthen a writer’s voice. Birds and characters alike contain entire stories in images, real and imagined.

“Watching and observing birds and writing fiction have influenced each other for me,” she says. “It’s not just that watching birds has helped me write fiction, or that writing fiction has helped me become a better birdwatcher. [Both are motivated by] an intense curiosity where I can watch the same thing for a very long time — not just more than five minutes, more than an hour, but for years. I’m able to watch how things develop and change over time and in context to larger issues in history.”

Tan has observed generations of birds nesting in her yard. During our interview, she noticed a purple finch, an oak titmouse and a junco — all within the course of a few seconds. Her birds, like her characters, leave impressions that last a lifetime.

Julia Halprin Jackson is a mother, fiction writer and editor of SJSU Magazine. She attended the Community of Writers thanks to the O’Dwyer Scholarship in summer 2025, where she had the chance to meet one of her heroes, Amy Tan. She is querying a novel set in Spain.

Julia Halprin Jackson is a mother, fiction writer and editor of SJSU Magazine. She attended the Community of Writers thanks to the O’Dwyer Scholarship in summer 2025, where she had the chance to meet one of her heroes, Amy Tan. She is querying a novel set in Spain.

MY TWO BABIES

by Tyler McAndrew

August 5, 2025

I’m writing this essay just a month before my debut book is to be published—a short story collection titled My Prisoner & Other Stories, which won the 2024 Nonfiction Prize from Mad Creek Books/Ohio State University Press. As I write, my five-week-old daughter is rocking gently in her swing, and my wife is sleeping on the couch next to me. It’s afternoon but the room is dark; the sky is overcast, and the sun is on the other side of the house. The baby has not let us get much sleep lately.

I’m writing this essay just a month before my debut book is to be published—a short story collection titled My Prisoner & Other Stories, which won the 2024 Nonfiction Prize from Mad Creek Books/Ohio State University Press. As I write, my five-week-old daughter is rocking gently in her swing, and my wife is sleeping on the couch next to me. It’s afternoon but the room is dark; the sky is overcast, and the sun is on the other side of the house. The baby has not let us get much sleep lately.

There are nine copies of my book on the shelf across the room, and one on the coffee table in front of me. I’ve been trying to read through it during the hours when the baby has me awake in the middle of the night, just to see what it’s like to read my own book—the fruit of sitting down at the writing desk nearly every day for the past eighteen years. I’ve read it a million times before, of course, but never like this, as an actual book. The baby has kept me busy, though, and so far, I’ve only made it a few stories deep. It’s a good book, I think. I hope it’s a good book. In a few weeks, when it is out in the world on its own, it will be a good book.

September 1, 2025

I’m trying to write about what it’s like to have a baby and a book come out into the world at relatively the same time. I’m afraid that a diary of notes on the topic might be all I can manage. It’s been about a month now since I began this essay and those first 237 words that you just read are all that I’ve gotten down. Today is Labor Day—just three days until my book’s official release date. The baby is about ten weeks old. She woke me up a little before 6am this morning. It’s noon now and the past six hours have disappeared in a blur. Where did that time go? I run through the morning in my head: preparing bottles, feeding, changing diapers, reading the handful of board books that we try to make a daily routine of, listening to her cry when I set her down in the laundry hamper for the few minutes that it takes me to wolf down a bowl of cereal. Surely, these things couldn’t have taken more than a couple hours at most.

This is what writing is like, too, I suppose. You slave over the thing, day after day, feeding it, listening to the story as best you can and feeling your way through one draft after another. Years go by like this and it’s easy to lose sight of all the work you’ve done. The oldest story in my book was written in 2010, before I even entered my MFA program, when I was just twenty-four. I’m a few weeks shy of thirty-nine now. It took five whole years of sending the book out as a manuscript before it finally got picked up. Who knows where all that time goes? It’s spent staring at a screen. Pushing commas around. Reading the same sentences over and over.

And then one day, when you’re neck-deep in all of it, you look down, and you say “Hi, Baby!” and the baby smiles back at you. The baby has learned how to smile! And it’s not just some neurological reflex, but a real, purposeful smile; she recognizes you and is happy to see you. Or at least happy to hear your voice.

I guess that’s what happens to all of that time. All those awful, screaming midnights and zombie-mornings risen from the tomb. It all gets fed to that one little smile.

September 2, 2025

If I were a lesser writer, this is probably where my metaphor would end. A quaint reflection on how I’m welcoming two babies into the world: my human daughter and my book. The number of times people have said something along these lines to me is, well, let’s say numerous. “It’s like you’re having two babies!”

But a better writer, I think, would present that metaphor—yes, my book is like my baby—and lure you into believing, for a moment, in the sameness of these two things before thrusting them very suddenly into the cold light of reality:

The book is there on my shelf. The baby is screaming again.

September 4, 2025

In all honesty, I strongly recommend having your first baby and your first book come out at the same time. Whatever anxiety you might have about publishing will be cast aside like another dirty diaper. Who has time to fret about pre-sales when there is a newborn screaming to be fed? How can you worry about what people are saying on Jeff Bezos’s Goodreads when you’re swabbing piss off the wall with a Clorox wipe at three in the morning? You may find yourself being asked to do interviews about the book for podcasts or for your city’s local alt weekly, and whenever you open your mouth to speak, you will sound like an absolute lunatic—sleep-deprived, rambling, barely able to string together a cogent thought, your social life of the past two months consisting almost entirely of cooing and gurgling and “Hi, Baby! Hi, Baby! Hi, Baby!”—and you won’t care, not even one little bit.

September 6, 2025

I remember, a few months ago, before the baby was born, I was sitting on the porch with two friends who are also both writers. One of them said something along the lines of “I bet having a kid will be good for your writing,” and—can you believe it? —I actually agreed, confessing that the same hope had been on my own mind. The idea was that I would be opening myself up to so many new experiences, new emotions, new little wrinkles of life that wouldn’t otherwise be possible without the perspective of parenthood. I’d inevitably become wiser, I thought, and that wisdom would surely manifest in my fiction. One of my friends brought up William Maxwell—a favorite writer of mine—and how his stories often have “big dad energy.”

And I confess, for years before my wife and I had even decided to have a baby, I often liked to picture myself, decades in the future, an old man—eighty, ninety, one hundred years old—scratching away at my stupid little stories, performing the sacred labor of imagination, and hopefully somehow wiser and kinder and maybe even a little happier in my old age because of it.

Maybe I’ll get there. But right now, a couple months into fatherhood, I still feel like the same old idiot that I was before.

October 2, 2025

I’ve so far avoided actually saying anything about my book in this essay. It’s been out in the world for a month now and I still feel like I haven’t figured out how to talk about my book. All these years spent with these stories, and I still don’t quite know what they mean or what they’re trying to do.

The stories in my book are often about kids; they are often set in the Rustbelt; they are often about the rippling effects of violence or about the difficulty of being able to save other people from their own tragedies. I recognize my world in the stories—the neighborhoods where I’ve lived, the strange encounters that I’ve shaped into narrative; the little glimmers of hope or desperation that I see out there in the world. A lifetime’s worth of psychological and emotional dust that has accumulated in my soul. But talking about my stories feels like trying to describe a person who I’ve known my whole life: Sure, I know them as well as I know myself—probably even better than that—but what do I say? Where do I begin? I might as well be pitching my baby.

Maybe this is where I actually make my baby / book metaphor. Any good writer knows the importance of uncertainty—getting out of your own way, giving yourself over to the story without imposing too much of your will on it. Stories have their own lives, even as you are writing them, and even if they are born entirely of your feelings and your memories, a good writer really only has so much control. You work and work and work, giving all of your love and attention to the words, trying to discern the story’s shape, trying to decide what’s best for it. But you don’t get to decide how tall a story is or what its first words are or how often it needs its diaper changed. All you can do is get out of bed when it calls.

Despite my MFA, I am a bit of a professional student (give me a chance to live as a pupil in a poetry workshop and I’ll drop everything to be there). I am a repeat participant in the poetry workshops in Olympic Valley for the past 21 years. I remember how terrified I was in 2004. I was away from my kids for the first time in their lives, in a stranger’s house with roommates I didn’t know (who would fast become my close friends). The waning sunlight in Olympic Valley was mesmerizing, and the early morning walks with the naturalist pointing out the crazy hidden lives of insects, birds and trees still echo. I remember the great hall where we all gathered back then, the week we heard that Julia Childs had died and that Martha Stewart had been convicted.

For Day One, I wrote a poem about my children as if they were jaded paper dolls. What I noticed about Sharon Olds’ large circle of sharing the next morning was that everyone that day had mentioned some kind of food in their work, like confessions of guilty pleasures. This was a novel system at the Community of Writers. Both student and teacher alike wrote poems for the next day’s workshop; and the teachers and students rotated every day so that no two combinations were the same. On Day Two I woke up super early and wrote a poem about hunger. That week I studied with Robert Hass twice. The food poem was the first time I’d ever encountered him in person and not on the page and I was still quite frightened despite his kind, constructive praise. By the end of the week, I had exhausted every thought in my head. Someone had pledged to write a sestina and urged everyone in that day’s workshop to try it. I thought why not, I can’t think of a single other thing to do. There I was desperately trying to write a sestina, knowing that my last day’s workshop would be with Bob, and I needed to at least try to write something, I could not go empty-handed. Hours of struggling and all I ended up with was this rambling fractured paragraph that did the work of a sestina but without any of the dignity and grace of the form. Surprising to me, it was well-received.

The shapeshifting poem is one of my favorites because it does interrogate itself as it interrogates the subject(s) of the poem. I love shape shifting more than I love form, which is funny because I live to live on that hill. Give me a sonnet or a pantoum assignment any day and I will make it happen. The formal constraint is what I really need to finish a poem.

Fast-forward to the pandemic and I am once again in the company of the poetry workshop masters only this time it is virtual. We are unable to break bread together or take walks in Olympic Valley or discuss anything. The workshops are a larger version of The Hollywood Squares, or perhaps the opening credits to The Brady Bunch. The magic that summer came from the wonderful craft talks every afternoon. This time around, I thought I would consciously write another shape-shifting poem. The craft talks were magic, with analysis and a lot of stellar instructions from the likes of Kazim Ali and Evie Shockley, Blas Falconer, Forrest Gander, and Brenda Hillman. Bob and Sharon were special guests administering wisdom with every word.

I went back to my old habits, got up at 5 AM, and like any good reporter met my deadline. I started writing these block paragraphs again. Only this time they were accompanied by these three line tails that presented themselves at the end. They were well received, but it was the last day’s poem about ecology and a pipeline spill I once covered as a daily newspaper reporter where I learned that I had written and had been writing haibun for the past four days. Accidentally. Well, as much as I love shapeshifting, I love the haibun even more. In my debut collection Self-Portraits Ex Machina, many of the accidental poems that I wrote that summer and subsequently are in its pages.

I was so lucky when I was in graduate school thirty years ago. I got to study with Lucille Clifton for two years. And I saw her again for the last time in Olympic Valley in 2008. I still remember her lessons, the most important of which was to read one’s work aloud. I had a different teacher several years later who, like me, was a former reporter now delving into the world of fiction and she helped me change the “I word.” I’ve crossed genres time and again in the past 20 years, but in the end, I’m still a poet who, once upon a time, wrote newspaper articles about crime and government. When it comes right down to it, no matter what I’m writing — even now, embarking on a memoir now about my family’s relationship to food in famine-struck India during WWII — I’m still a poet. I’m still considering word choice. I’m still considering line breaks and syllabics. I’m still employing anaphora and using the braided ladders of pantoums.

This teacher said that my newspaper reporting days was not an infection; that all the writing I have done in other genres informed my poetry – it did not take away from it at all. It has given me permission. And that’s how I shapeshift my way around any poem I write.

I did finally write my first successful sestina in 2013 (I’m a professional student, remember?) in Mexico. What I have come to learn is that I will always be a poet, I love opening my toolbox and using something I’ve learned from the poets before me to help sharpen my prose.

Shape Shifting

Since I am the unemployed poet who hasn’t

published in eight years my husband

says I have to find an accountant to help us save.

I wanted to write a sestina

and since there are five of us, I asked each one

for a word: Mine is collection.

My husband says spoil and the girls say present, rose, bend.

The accountant adds close.

At first I thought I was writing about the migration

of monarchs, the milkweed pit-stops

between Vermont and the mountainous forests

where they’re known to swarm whole

groves of pine and eucalyptus in central Mexico

before trekking back north to die.

But it is hard to find six different uses for fly

besides the obvious ones about sex

and flight and who needs to read another sestina

about endangered butterflies

whose stained-glass wings rival cathedral windows

in Europe? Cities I’ll never see

again since my now ex-husband is running off

with the accountant and currently has custody

of our children while I have custody of the bills.

Then I think I’ll use the leftover material

to fashion a sestina about fairy

tales and benevolent godmothers who rescue

distressed damsels the way

my lawyer refinishes distressed furniture

on weekends that other people have warped

by using the chair arms as coasters

for their espresso or chardonnay. But I get tired

of the repetition of distress

and I don’t want to write about my attorney’s

obsession with other people’s inability

to manage their own possessions and nobody

would read another rewrite

of Cinderella, however compelling the form.

Besides, fairy tales are for children

and I can’t even see mine without written

permission from my ex-husband’s new wife

who now knows every scintilla about me—

that mousy-haired, green-eyed, statuesque

accountant of marital discord. I write out by

hand my fractured phrases and disjointed

thoughts and take to them with a pair

of scissors, my black-inked scrawl now on long

strips of white paper; I unravel a pile of wire

coat hangers my ex-husband will

no longer use to hang up his double-

breasted jackets and monogrammed silk

shirts and fashion a mask of a face that doesn’t

rival a real artist’s but I am pleased

with it and with the help of glue from the kids’ art

caddy I make a literary mummy

face, words swirling between the bell-shaped

ears. Rose and bend on each eye, spoil

and present on the lips and collection just

at the chin. Close on the forehead. The whites

of the eyes are like egg whites surrounding

a poached egg and I am hungry

for the first time in months so I wash my

hands and hang up my new face on a nail

that used to hold up a picture of my ex-husband

and me and I go downstairs

and cook breakfast and decide I will be

an unknown multimedia artist because who needs

another sestina in the world?

Haibun

Frederick Douglass—Unexpected 1884 is a short play with a long history.

Few men in American history have a more powerfully dramatic story than Frederick Douglass. Born a slave, he escaped to become the author of three autobiographies over his lifetime, during which time he became an internationally celebrated abolitionist, women’s rights activist, and the most photographed man in the 19th century—more so even than Abraham Lincoln. That was strategy on his part.

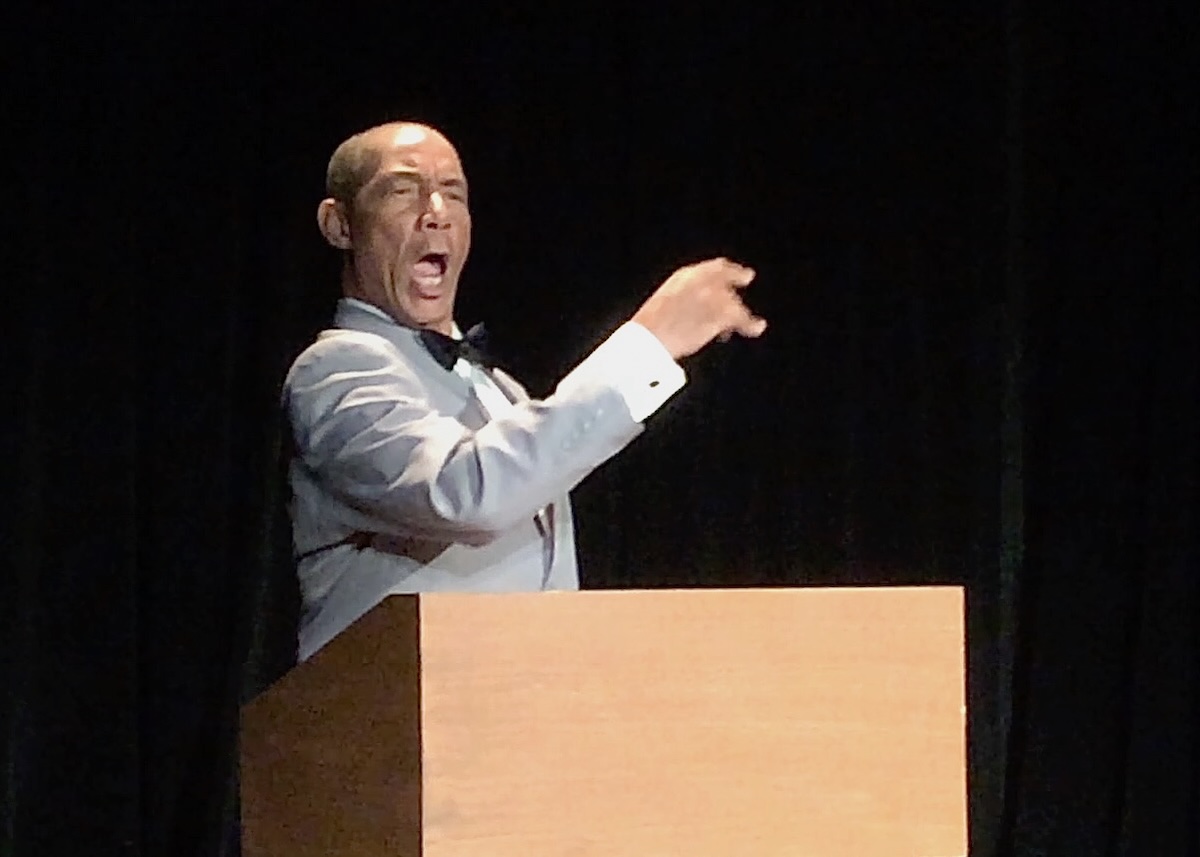

My 15-minute historical play about Frederick Douglass recently ran at the Stella Adler Theatre in Hollywood as part of the show “In Response: Rise Up!”, a presentation by Towne Street Theatre, which bills itself as “LA’s Premiere African-American Theatre Company.” Frederick Douglass—Unexpected 1884 starred Adrian Babatunde Thomas in the title role, and De Ann Marie Odom as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with Kimba Henderson directing. The play had previews October 4th and 5th, and opened on Friday, October 10th, with three performances per weekend through November 2.

The earliest version Douglass was a five-minute monologue written in 2004 specifically for a night of monologues presented by the group Playwrights 6 at Hollywood Church Court Theater inside the Hollywood United Methodist Church. Actor Elliott Williams (Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job) performed the role. As I wrote, he and I discussed the monologue, which continued to be revised until shortly before the performance. Elliott offered me counsel from a black man’s perspective that improved the piece. All these years later, neither Elliott nor I recall exactly what the advice was, only that it corrected something that a white writer had gotten wrong about the black experience.

Over the next several years I continued to read about Douglass and also about Women’s Rights pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton. I workshopped the short piece a few times at Fierce Backbone, a 501c3 development company that I co-founded with six others. One key element was added: an examination of the professional and personal relationship of Douglass with Stanton. As I read separate accounts of each activist, I noticed the overlap of their careers and felt that there was an attraction between the two. I do not believe they ever consummated their relationship physically, but I feel the evidence is there that they were closer emotionally than simple political allies.

For a dozen years they worked side by side for the abolition of slavery and the rights of women, and universal suffrage. That changed after the Civil War, when the men (and some women) of the abolitionist movement maintained that women should put their push for suffrage on hold because the country would never support both black men and women getting the vote at the same time. This infuriated Stanton, who began giving speeches against the proposed 15th Amendment, complaining about unschooled “Sambo” (and “Hans and Patrick and Yung Tung”) getting the vote when educated white women would be denied it. Douglass called her out publicly regarding her derogatory language, yet while he repudiated the words, he never repudiated the woman. Why not? I wondered. Eventually I found what I believe to be the answer, and it became the emotional core of my story.

In 2014, Fierce Backbone Managing Director Victoria Watson asked me if I’d be interested in presenting my Douglass play as part of a Hollywood Fringe production titled Lincoln Adjacent: Three Plays NOT About

Directed by Julianne Just, Lincoln Adjacent won a Producers Encore Award, meaning a couple of additional performances. Friends of mine and of Rif’s urged us to develop a full length version.

In the latter part of 2014 I did expand Douglass, and workshopped it some more at Fierce Backbone’s Monday night workshop readings. Actor Doc Farrow (Young Sheldon, Fresh Off the Boat; Arrested Development) did a full read of the new draft during several FB workshops, where members gave feedback. One suggestion I got came from Ted Lange (The Love Boat). Ted writes plays based in the time of abolition work and the Civil War, including John Brown’s raid. Ted suggested that I cut Douglass relating his connection to Brown and the raid, saying that everyone already knew that story. I disagreed, but at the time took the note and eliminated John Brown from the story.

By 2015 I had enlisted a black director, David Wendell Boykins (Concrete River), who had been recommended to my wife, Consuelo Flores, by actress Tiwana Floyd. At the time Consuelo worked in the Member Education Department at SAG-AFTRA. I finished a full-length draft of what was now titled Frederick Douglass—Unexpected, deciding to have the story be of Douglass presenting on stage the first show of his valedictory national speaking tour. I envisioned the one-man play being the Douglass version of Hal Holbrook’s long-running Mark Twain Tonight!. As I crafted the piece, whenever possible I used Douglass’s own words, which I gleaned from his speeches, his three autobiographies, from his letters, and from what newspapers and his contemporaries, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, wrote about him. I had Douglass recounting key points in his life and political journey, lamenting the decline of Reconstruction. Blessed with a wealth of material, I wound up throwing in the kitchen sink (John Brown after all)…

When Rif Hutton gamely read my bloated draft aloud at his home to David and me, it ran a ridiculous three hours!

Working with David and Rif, I trimmed the story down to about two hours and we presented a workshop reading to an audience at The Flight Theatre, a small venue upstairs at the now-defunct Complex in Hollywood. The reading was well received. Audience members filled out a short questionnaire that helped me further edit the story.

Late in 2015 Rif dropped out of the project due to personal and professional reasons. Admittedly, it was a lot of time-consuming work for no pay. Eventually, David and I settled on veteran movie actor G. Smokey Campbell (Bagdad Cafe; Devil In a Blue Dress) to portray Douglass.

In the spring of 2016 we mounted for a full workshop production at the Ruby Theatre at the Complex, which my wife Consuelo G. Flores produced.

Hair was a big issue. I called Rif to find out how he had done the hair. Turned out he had a paid a professional who would fix the hair each show. He gave me her number. She told me it would cost $300 per show. I told her it was a workshop production and asked if we could maybe get a discounted price. “That is the discount.” And Rif had never said a word. That is commitment to the role.

Soon afterwards, we found out how hard it is to find an off-the-rack Frederick Douglass wig. The closest thing turned out to be an Albert Einstein wig from Hollywood Toys & Costumes. In the end, we decided to go with Smokey’s shaved head, a suit from L.A.’s garment district, and a bowtie. Kind of a Malcolm X look. Smokey made it work.

The workshop production was well-attended, and again we provided the audience with a short questionnaire to help me get ideas on revisions.

Once the revisions were done, the issue became funding. I needed to find the money to mount a full production for a decent run.

In July of 2018 I reached out to Julius Tennon, Viola Davis’s husband, at JuVee Productions. I had worked as a crew member on an Austin, Texas PBS children’s video back in the early 1980s in which Julius was one of the actors. The JuVee website allows people to email the company. I used the PBS work as bridge to connect us and he responded. In my message I reminded Julius of who I was and pitched my play. A day or so later I got a call from him and he asked me to email him the play. By and by I met him at his office. He was interested. Several months later my wife Consuelo and I met in the upstairs office of the Robey with Julius and Robey co-founder and Artistic Director Ben Guillory to do a read-through. Julius decided he was going to portray Douglass himself, despite his very busy schedule as president of JuVee productions.

On July 21, 2019, the Robey Theatre Company, in association with the Latino Theatre Company, presented Julius Tennon in a reading of Frederick Douglass—Unexpected, directed by Ben Guillory. We had about 50 people and Ben moderated a feedback session afterwards, at which time Ben told the audience that he expected to present a full production by early 2020.

In the middle of the following week, Ben and Julius came to Consuelo’s and my house for a “post mortem” based on the audience feedback and our own observations. One criticism that came from several black women in the audience was that there was not enough about Douglass’s wife Anna in the play, and too much about the various white women activists who helped him throughout his career.

I explained to Ben and Julius that Douglass rarely mentioned his wife in his writings and virtually never in his speeches. Since I was hewing close to his own words, and because I am a white man, I didn’t feel comfortable extrapolating from what is known about his relationship with his wife and having him talk about that part of his private life to the public. Both Ben and Julius told me to go right ahead and use my creative imagination to increase Anna’s role in the play (and reduce the stage time of stories about the white women.)

By August I had a new draft that both Ben and Julius liked. Due to Viola Davis’s increased production schedule, which Julius was greatly involved with, the Robey production kept getting pushed back six months here, six months there. Ultimately, the pandemic combined with Viola Davis’s growing success, compelled Julius to end his association with the project by February 2023. He was simply too busy running the wildly successful JuVee Productions, as well as acting in some of the productions.

In March of this year (2025), Towne Street Theatre put out a call for submissions of short plays for their show “In Response: Rise Up! 2025.” I decided to pare Douglass back down to almost what it was at the Hollywood Fringe. Towne Street selected my play as one of nine to be presented.

Sarah Bauer, Towne Street’s COO, told me the Towne Street team suggested having an actress on stage speaking Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s words, although without direct conversation with Douglass. She would be a memory presence on stage. Immediately I saw the advantage to this and agreed. I modified the script to reflect that change. It worked so well that I will look at having other characters on stage with Mr. Douglass when I take another look at the full-length version.

As an end note; I was not at any of the rehearsals for In Response, and so was pleasantly surprised when I saw Adrian Babatunde Thomas in full costume, replete with the iconic hair (in everyday life Adrian has a shaved head). When I spoke with him, he let me know that he had gotten the wig himself (shades of Rif Hutton), but even more wonderful, he had styled it himself!

FREDERICK DOUGLASS—UNEXPECTED 1884

CAST:

FREDERICK DOUGLASS. African-American male, (historically) aged 66

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON, White female, (historically) aged 69

LIGHTS UP ON FREDERICK DOUGLASS pacing in his office, studying an unopened envelope.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

When they brought me the news, all those years ago, I told them they were mistaken; wrong. Elizabeth Cady Stanton politicking for woman suffrage at the expense of theblack man? The very idea! Then I went to your rally and heard for myself your venomous trespass against all that we had believed and been through together and my eyes stang, I tasted bile.

Now, after 16 years, when I am under siege, I receive this letter out of the blue. No return address, simply “E.C.S.” penned with a flourish in the corner. I dare not open it. Yet my thoughts have their own will and drift back to the happy afternoon when you and I first met.

MUSIC: “The Blue Juniata.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

It’s the Year of Our Lord 1841, I have escaped from my master scarcely three years prior. I am 23 years old, no longer Frederick Bailey the slave, but Frederick Douglass the new man. To a packed lecture hall of predominantly white people I give my second ever public speech as a general agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

After shocking that well-heeled audience with reports of my experience as a slave, at the home of a prominent Quaker family I get introduced to assorted abolition advocates. Then there arises before me the most comely white woman I have ever laid eyes on.

MUSIC FADES. LIGHTS UP ON ELIZABETH CADY

STANTON UPSTAGE. She is Stanton in Douglass’s memory, not actually there.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

My hostess introduces you. You are a young wife roughly my own age, scarcely a year married, and I see you are with child. My Anna and I have been married for nearly three and have a daughter and son.

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

Bravo, Mr. Douglass!

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

You offer me your ungloved hand scented with night-blooming jasmine. At the time I am still shoveling coal for wages, so my callused hands are like leather. But you do not flinch. Indeed, you tell me:

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

You stood up there like an African prince—dignified and powerful, grand in your physical proportions, majestic in your wrath. You paced the stage like a Numidian Lion. Fresh from the land of bondage, you portrayed the bitterness of slavery, the humiliation of subjection, with more keen wit, satire and indignation than a roomful of these pale churchmen could ever muster.

Your denunciation of our national crime, of the wild and guilty fantasy that men can hold property in man, poured out of you like a storm of insurrection that fairly made your hearers tremble. It was delicious!

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

I scarcely know what to make of you, Mrs. Stanton. With the skill of a young lady who grew up at the knee of your father, the judge, you aptly and logically set before me the wrong of what you deem the “aristocracy of sex,” the injustice of excluding females from voting.

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

Every argument for the negro is an argument for woman, and no logician can escape it.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Nor can I.

Quite simply, Mrs. Stanton, you astonish me that day—not only with your lawyerly argumentation, but more so, and mostly, with your transparent acceptance of me, with your blithe and instant camaraderie.

You do not, as so many well-meaning white people do, find my cultured literacy surprising. You take it as a given, something natural.

(beat)

I am not unexpected to you.

MUSIC: “FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN” on violin.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

From that day forth, you and I become evangelists together in the cause of freedom for black people, full citizenship for women, and the right to vote for all. Universal suffrage. I have never entered upon any work with more heart and hope.

SEGUE TO: “Battle Hymn of the Republic” playing slowly, like a dirge.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Ah, there were so many casualties wrought by the bloody War of Emancipation. I fear my great and special friendship with you, Mrs. Stanton, was yet another.

MUSIC FADES OUT.

I confess that, in fear, I go along with the constricting and demanding logic of white male leaders of the movement—I join them in insisting that women postpone their demands for the duration of the struggle to reach the shore of negro, male, suffrage.

Three years after the war ended, the anti-slavery forces gain the crown jewel of Emancipation: the 15th Amendment to the Constitution. Black men now have the vote, but women, black and white, do not.

In your speeches you begin parading “Sambo” as an ignorant monster possessing the ballot, while women are denied it.

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

Better to be the slave of an educated white man than of a degraded, ignorant blackone!

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Mrs. Stanton! You presume to identify your cause with that of the slave woman. Forgive me, but the oppression of white women seems trifling when compared with the stupendous and ghastly wrongs perpetrated on the slave woman!

In your glistening eyes I see your pent-up fury, your trembling sense of injustice, and my heart almost breaks. I catch again the scent of night-blooming jasmine….

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

I only ever desired that we go into the kingdom together.

She turns away.

LIGHTS DOWN ON ECS.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Can’t you see my logic? For negro men, getting the vote meant not being bull-dosed by a whip, hanged from a lamppost, brains dashed out on the pavement!

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Not being hunted and shot down for daring to speak your mind to a white man!

(beat)

Or so I thought at the time.

(sings “Trouble So Hard” a cappella)

Oh Lord, trouble so hard

Oh Lordy, now, trouble so hard

Yes indeed, my trouble is hard

Don’t nobody know my troubles but God.

As the years have rolled on, I have come to realize that yours is the greater cause, since it comprehends the liberation and elevation of one half of the whole human family.

In the heart of my heart I realize now that the day I asked you to set aside woman’s suffrage—even momentarily— that was my betrayal of you, and of myself. I have been my own Iago.

(beat)

It is difficult to admit, but I have come to realize I’ve done very little in this world in which to glory except one act: nearly 40 years ago, at that very first Woman’s Rights Convention, spurred by your vast act of conscience and surpassing courage, I rose after you had spoken, rose before all those white men and women and my hands trembled because I fully fathomed the radical import of your proposal. But rise I did, and seconded your Resolution Number 9. I spoke in favor of women voting. And the resolution passed.

MUSIC: “Wade in the Water.”

In that, I certainly glory. You see, when I ran away from slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people. But when I stood up for the right of Woman, for the right of you, Lizzie, self was out of the question. In that act, which you inspired, I found a little nobility.

MUSIC FADES OUT

On August 4, 1882, after 44 years of marriage, my Anna passed from this world. She is no more. Now, after a year and a half of grieving, I have married again, to Helen Pitts, a white abolitionist and feminist. If you think about it, my choice is symmetrical: first wife was the color of my mother, my second is the color of my father.

Regardless, my enemies pillory me. My closest friends, both colored and white, disparage me. “How can you betray the ebony Anna’s memory?

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

How can you marry that woman, twenty years your junior, with her peaches-and-cream complexion and her fiery tresses?” Ye gods, even my daughter Rosetta and a good portion of my family spurn my fresh union as an affront to Mother, to Anna.

I did not look for another wife. The fact remains that Cupid’s aim is a mystery.

(holds up a letter)

And to cap the climax, when I am at my most vulnerable you have sent me this letter.

LIGHTS UP ON ELIZABETH CADY STANTON.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

What’s the Shakespeare line? Shall we not revenge? I dare not open this, and yet the hint of night-blooming jasmine draws me in. It seems I’m a glutton for punishment.

He rips open the letter, reads:

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

My dear Douglass…

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Oh, beware false civility.

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

(ahem) My dear Douglass, Allow me to…

(beat, Douglass expects the worst)

—congratulate you on your recent marriage. When the hue and cry began, I felt as if I would like to fire ten pounds of dynamite at all those ridiculous prejudices of color, but the contemptible parties were too small for an outlay of dynamite, so I took to ridiculing the bloviating jackasses, bombarding them with sarcasm.

My friend, if it is any comfort for you, know that my sympathies are with you, as they always have been; know that there is another soul who, though absent, is walking with you. With my kind regards to your wife, and my sincere wish…

(beat)

…that all the happiness possible in a true union be yours.”

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

(looks up from the letter)

My dear Mrs. Stanton, you still astonish me.

Violins play upbeat “Violin Concerto in G major, Op.2, No.1,” by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (“Black Mozart”).

LIGHTS DOWN.

Stephen Blackburn participated in the Community of Writers in 2003 and 2005. He grew up in Corpus Christi, Texas, and was an endowed James Michener Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin.

Recently Emerging Screenwriters tapped his screenplay Fatal Detour as a 2025 Top Ten Finalist in the Thriller Screenplay Competition.

He authored the short-story collection The Extinction of Rhinos in Mexico: Nine Tales of Life and Death (Xlibris), which has been praised for its compelling narratives set in the Southwestern United States. He also co-authored Each One Teach One: Up and Out of Poverty; Memoirs of a Street Activist (Curbstone Press/Northwestern University Press) with Ron Casanova, a memoir that chronicles Casanova’s journey from homelessness and addiction to activism. This work was hailed by Booklist as “an eloquent voice for Americans too often ignored or scapegoated.

The stage production of Blackburn’s noir murder mystery The Rock of Abandon, set in ancient Athens and featuring the playwright Euripides as the detective, received praise from Backstage as “a Grecian extravaganza…always engrossing and fun to watch.” His screenplay Fatty & Buster contributed to his receipt of the Michener Fellowship.

Blackburn co-founded Fierce Backbone Theater Company in Los Angeles. He resides in Los Angeles with his wife, Consuelo G. Flores, a renowned Day of the Dead altarista, playwright, poet and cultural advocate.

I have begun two Laureate projects. For the first, the Favorite Poem Podcast series, I invited twenty-five poets who either live in, or have lived in, Mississippi, each to choose a favorite poem in the public domain—not one that they wrote—and to read it, talk about it, and talk about its author in conversation with me for about fifteen minutes. A former student of mine, Clay Jones, has a professional podcast business here in Oxford, and it has been wonderful to work with him and his colleague Jill Graves either in their studio or on Zoom. I launched the series with Emily Dickinson’s “A Bird—came down the Walk”; then we’ve had podcasts on Shakespeare’s “When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,” Marianne Moore’s “The Fish,” H. D.’s “Oread” and “Leda,” and Margaret Walker’s “Jackson State, May 15, 1970.” These are being released once a month over Mississippi Public Radio and I hope teachers as well as the general public will find them fun and useful.

The second project was begun by my predecessor, Catherine Pierce; it was so successful that I wanted to continue it. It’s a poetry competition called the Mississippi Poetry Project for grades K-12, in which students write poems to a prompt, which are then judged within their schools, and the best three from each grade from each school are sent to me. I will line up people to help judge the winners. All schoolwide winners will have their winning poems published in a contest anthology, and statewide winners will be invited to share their work at next fall’s Mississippi Book Festival. Here is this year’s prompt:

Writing About Nature: A Place I Love (or, A Place I Hate)

This prompt asks you to think about experiences you have had outdoors, and choose one to write about. This experience might be something that happened once, or something that happened many times. It might be something that happened on vacation, or something that happened visiting family, or in a neighborhood park, or in your own back yard. The possibilities are wide open. The important thing is that it involved being outdoors.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself, to get started:

*What is the most beautiful place in nature that you have ever been?

*What are your favorite flowers? Plants? Trees? Insects? Animals, besides pets? Sounds in nature? Colors in nature? Land formations—mountains, swamps, fields, meadows, forests? Bodies of water?

*What is the happiest experience you have had in nature—hiking? Fishing? Taking photographs? Playing with a pet? Playing with friends? Having picnics with your family? Sleeping under a tree? Exploring? Just sitting quietly?

*Have you had an experience in nature that you hated?—Getting poison ivy? Getting lost? Getting hurt? Getting bitten?

*Do you have a secret hideaway? Do you grow things? Do you study things in nature? Do you play games outside? If you had a wish for the place you love, or for the place you hate, what would it be?

Another interest of mine is working with incarcerated writers. Three times, I’ve taught at Parchman, the Mississippi State Penitentiary, as part of the Prison to College Pipeline program at the University of Mississippi. The first two semesters, I team-taught with my colleague Patrick Alexander, who co-founded the program; he taught literature of incarceration and freedom, and I taught creative nonfiction and poetry writing. The third semester, I taught solo—both reading and writing poetry. My students also ended up writing their life narratives, and these were published in About Place Journal. Here is a link to these extremely moving narratives: https://aboutplacejournal.org/issues/shaping-destiny/new-writings-from-parchman/. I have agreed to lead one workshop at the Marshall County Correctional Facility in November; we will see what develops out of that. I may also be teaching again at Parchman sometime in the next year.

I mentioned About Place Journal. This is the online journal published twice a year by the Black Earth Institute, of which I am a senior fellow and board member. The Black Earth Institute was founded by Michael McDermott and his wife Patricia Monaghan (now deceased) when George Bush first got elected. They figured they’d either spend the next years drunk or figure out how to take action—so the Black Earth Institute, located outside Black Earth, Wisconsin, was born. It is a small group of poets and scholars whose work focuses on social and environmental justice and matters of the spirit. Fellows are chosen for a three-year term, and some continue as senior fellows afterwards. In the past we had yearly retreats at the home of Michael and his wife Charlene, but Michael’s health issues have forced some changes recently, and the journal is the main way the organization will continue. I encourage you all reading this to check out calls for submission; the journal publishes poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and visual art, and the issues are really beautiful. The new call will come out in November. The current issue’s theme is “On Freedom,” and I’ll be coediting one with Laura-Gray Street in about a year, intended to mitigate against so much that is destructive in the world, with the theme “On Beauty.”

For 34 years I taught in the English department at the University of Mississippi, before retiring in 2022. I taught American literature, environmental literature, and—in the MFA program—poetry seminars and workshops. One thing I’m proudest of during those years is my role in creating the Interdisciplinary Minor in Environmental Studies—a small program (hey, this is Mississippi!) but one that sent its graduates out to do really challenging and creative work in environmental and social justice issues. I was also faculty sponsor for Hill Country Roots, a student organization that raised trees to plant around this community, which has been the subject of careless runaway development. I’m also proud of the poets I taught, the writing and teaching they have continued to do, and the brilliant books they have published.

And finally, as Poet Laureate I want to create a project that will involve working with communities all over the state. The idea for this comes from what my Black Earth Institute colleague and friend Lauren Camp did as Poet Laureate for New Mexico, holding crowd-sourced writing activities in various places, then collecting what people wrote and building poems out of it to celebrate each community’s sense and history of place. I hope to start organizing this within the next year.

So that’s a little bit of what I have been up to as Poet Laureate. As a writer, my most recent project is a poetry/photography collaboration with Wilfried Raussert, my long-ago graduate student who went on to become a professor in Germany. Willie, who is a film-maker, musician, and photographer as well as a scholar, spends a lot of time in Guadalajara, and this project has involved writing poems in response to his photographs of street art in Guadalajara—then, the poems have been translated into Spanish by members of the Women in Translation group based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The project, Into the Chalice of Your Thoughts / De tus pensamientos, el cáliz, was displayed at the 2023 Guadalajara Book Festival and published as a book by the University of Guadalajara Press. But since the book is only available in Mexico, we have doubled it in size, given it the new title This Moment Between Time / Este instante, entre tiempos, and begun looking for a publisher in the United States. (If anyone has any suggestions, please let me know!) Here’s a link to some work from this project: https://edgeeffects.net/poetic-encounters-across-borders/.

And of course, as a coeditor with Laura-Gray Street, my most recent project is Attached to the Living World: A New Ecopoetry Anthology. But since this was featured in a recent Omnium Gatherum, I won’t say more about it here—except, Trinity University Press, which published both The Ecopoetry Anthology and Attached to the Living World, has just learned that it will close at the end of 2026, so I encourage everyone to support the press and buy the book!

Ann Fisher-Wirth is Mississippi Poet Laureate for 2025-2029. Her eighth book of poems, Into the Chalice of Your Thoughts, is a poetry/photography collaboration with Wilfried Raussert and translations of the poems into Spanish by the Women in Translation collective (U Guadalajara Press, 2023). Her seventh book of poems is Paradise Is Jagged (Terrapin Books, 2023). With Laura-Gray Street, Ann coedited Attached to the Living World: A New Ecopoetry Anthology (Trinity UP, 2025). A senior fellow of the Black Earth Institute, she received the 2023 Governor’s Award for Excellence in Poetry from the Mississippi Arts Commission. She has had residencies at Djerassi, Hedgebrook, Storyknife, and elsewhere; Fulbrights to Switzerland and Sweden; and awards including a Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Prize, the Rita Dove Prize, and 16 Pushcart nominations. Ann retired in 2022 from the University of Mississippi.

POKEWEED

by Laura Cresté

A small stalk, it grew in the alarming

way of tumors, grew as if dreamed.

It was hard to see the problem at first,

weeds sprung within my mother’s rosebush,

like spotting the flaw in an emerald.

There’s talk of selling the house,

which needs a new roof, and I take

my reluctance into the garden.

I am trying to reverse years of disregard,

trying to care for the plot that raised me,

where my lavender died as soon as it was bedded,

though the lamb’s ear held on for some seasons.

Bound in ivy, beneath the evergreens, crouches the unsettling

statue of a boy, Buddhalike but not the Buddha,

skull preternaturally round, gifted by an ex.

I led him past the gate, knelt in the tall grass,

didn’t feel the mosquitos until later.

Stray cats lapped rainwater on the pool cover.

Before it was drained, I swam naked

and sometimes fully clothed;

when you’re a child, novelty is the point.

I don’t know if I was happy but here is where I was.

On the back stoop, hunting meteors with my father:

I was ten, it was winter, we could see our breath.

Now I dig into the ruts between brick,

chasing the fleshy taproot down

to where the dirt changes color.

I uproot all but wild

strawberries, tiny and crystalline,

perfect for the dollhouse lost to a flood.

I know conversation with the land only goes

one way. But when I pull at the weeds,

the weeds, I think, pull back.

“Pokeweed” from In the Good Years © 2025 by Laura Cresté. Appears with permission of Four Way Books. All rights reserved.

“Pokeweed” closes my debut collection, In the Good Years. In a way it continues work that began at the Community of Writers, which remains my most productive writing week yet. It was June 2020 and so this was the “virtual valley” summer, which I joined from my in-laws’ home in western Massachusetts, where my husband and I had decamped to in March 2020, intending to stay for a couple of weeks, just until the virus calmed down. By the start of that first pandemic summer, all I’d written for months were anxious journal entries. I was worried about the expectation of producing a new poem every day, but to my surprise, the writing came easily. Five of the seven poems I wrote in the virtual valley (“The Mothers”, “Inheritance”, “This Is Just To Say”, “Gentle or Not,” and “Socrates with Fleas”) appear in my debut collection.

A year later, during my fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, I was looking for a way to exit my book. A sense of place is important to me in poetry. I’d spent most of my fellowship writing either about the landscape of Provincetown—in an eleven-page poem about a dead humpback whale that had washed ashore during our time there—or about Argentina’s military dictatorship of the 1970s-80s, which my family lived through. These are important threads in my book, but they’re not the whole story. In ending the book, I wanted to return to my childhood home and the space of the garden. (Something like Eliot’s insistence that we “arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”)